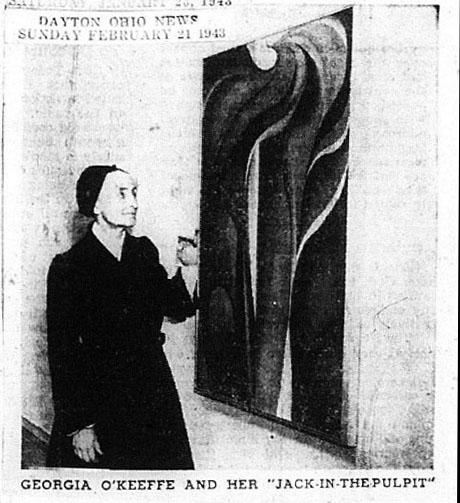

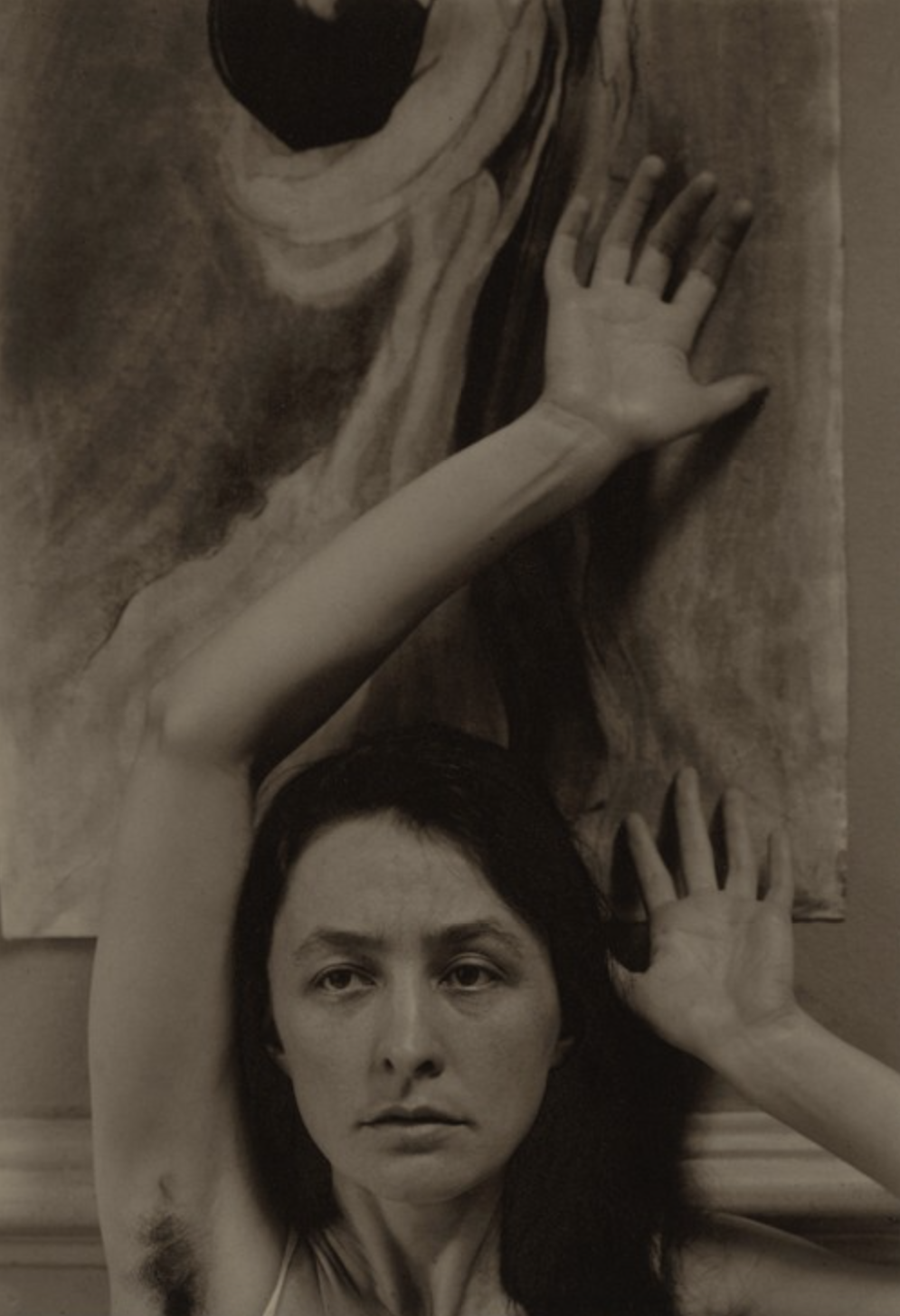

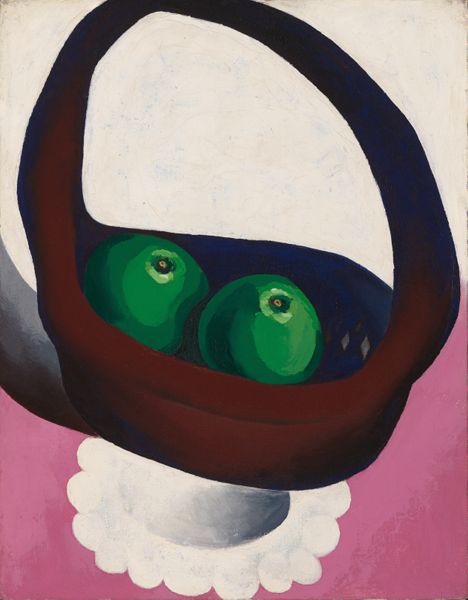

Georgia O’Keeffe proved to be the perfect artist for up-and-coming Texas art museums to stake their claims as both regional and national institutions. Though not a native Texan, O’Keeffe was considered “western” and “Texan” enough for these museums to celebrate her regional importance; she had lived and worked in New Mexico from 1929, and she taught art in Texas in the 1910s (figure 1) while producing a vast body of innovative work.1 But O’Keeffe was more than just a “regional” artist. She was nationally renowned and the highest-earning woman artist in the United States for decades (and still is today2). By showing her art, the Texas museums could attest that they, too, were competing on a national stage. For example, while O’Keeffe’s first major retrospectives occurred at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1943 and at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York in 1946, her third retrospective was held in 1953 at the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts (now the Dallas Museum of Art, or DMA)—a show that secured the DMA the acquisition of Bare Tree Trunks with Snow (1946, figure 2).3

This Dallas institution, founded in 1903, began showing O’Keeffe’s work by 1936, launching its grand reopening after renovations of its Fair Park location with a show of O’Keeffe’s work in conjunction with the Texas Centennial.4 And the DMA since then has held no less than 10 exhibitions dedicated to O’Keeffe.5 But the DMA is just one of many Texas museums that have embraced and supported O’Keeffe’s art.6 To be sure, a distinctly reciprocal relationship developed between O’Keeffe and Texas museums in the mid-twentieth century. O’Keeffe received significant attention for her work in Texas, from collectors, museums, and museum visitors, all of whom helped to establish her as a blue-chip American artist. But these museums also drew upon O’Keeffe’s strong reputation to gain their own national recognition as major art institutions.

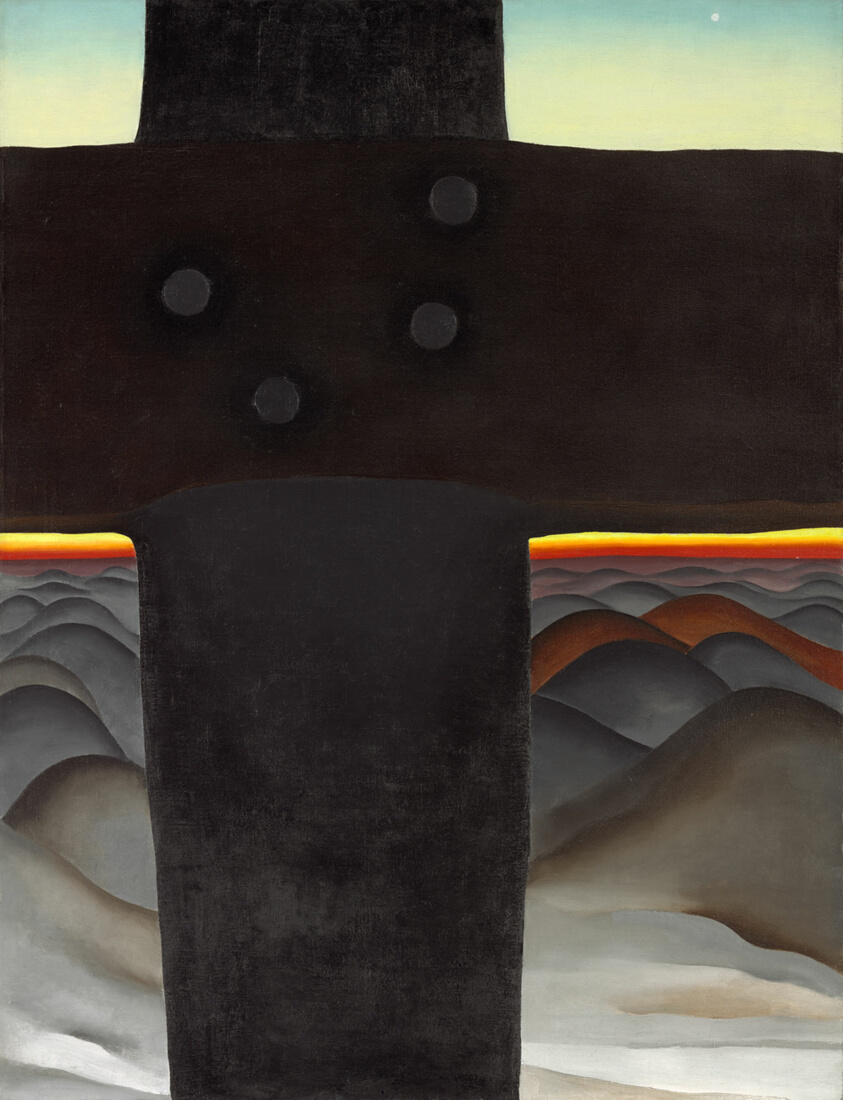

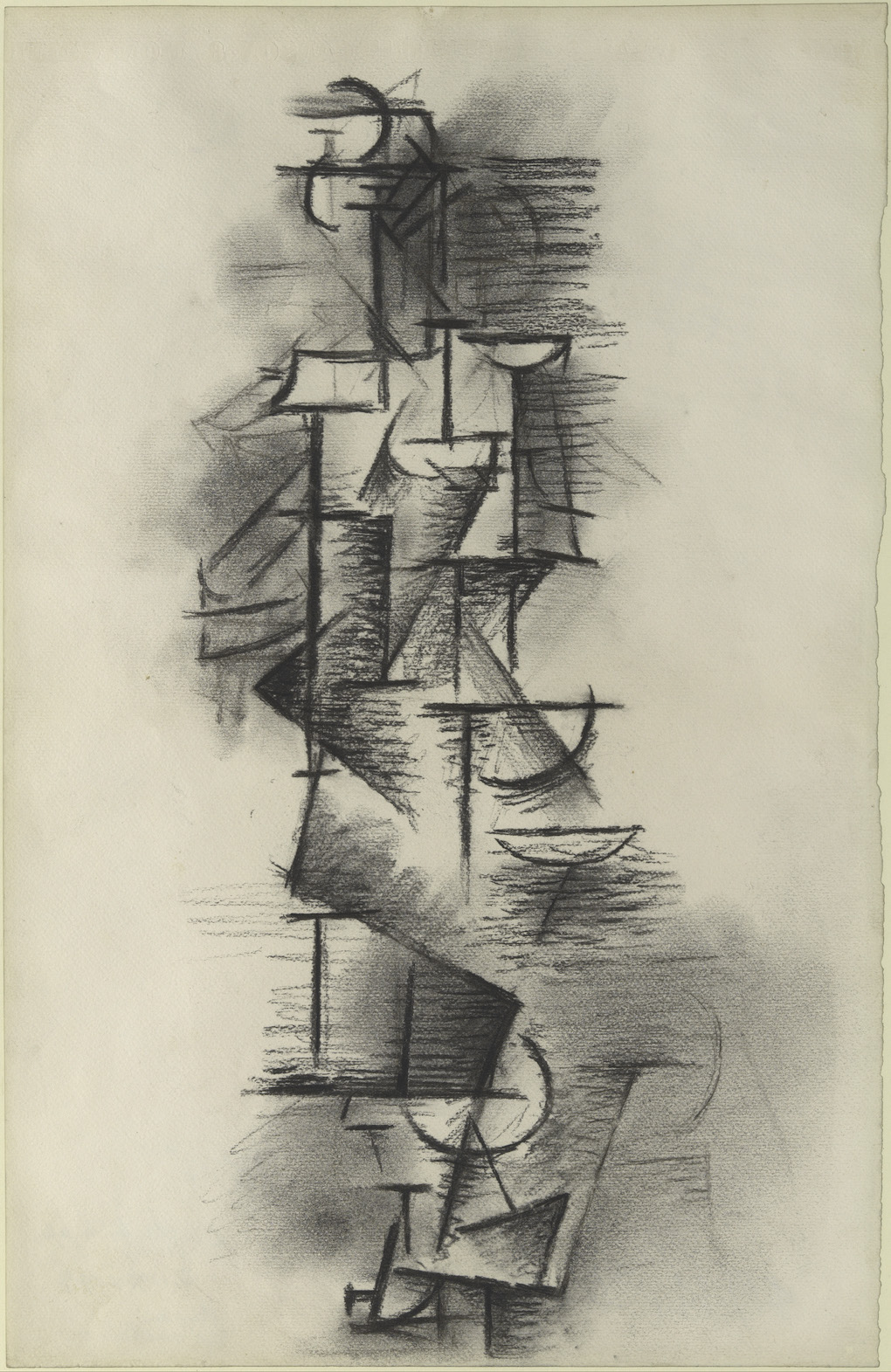

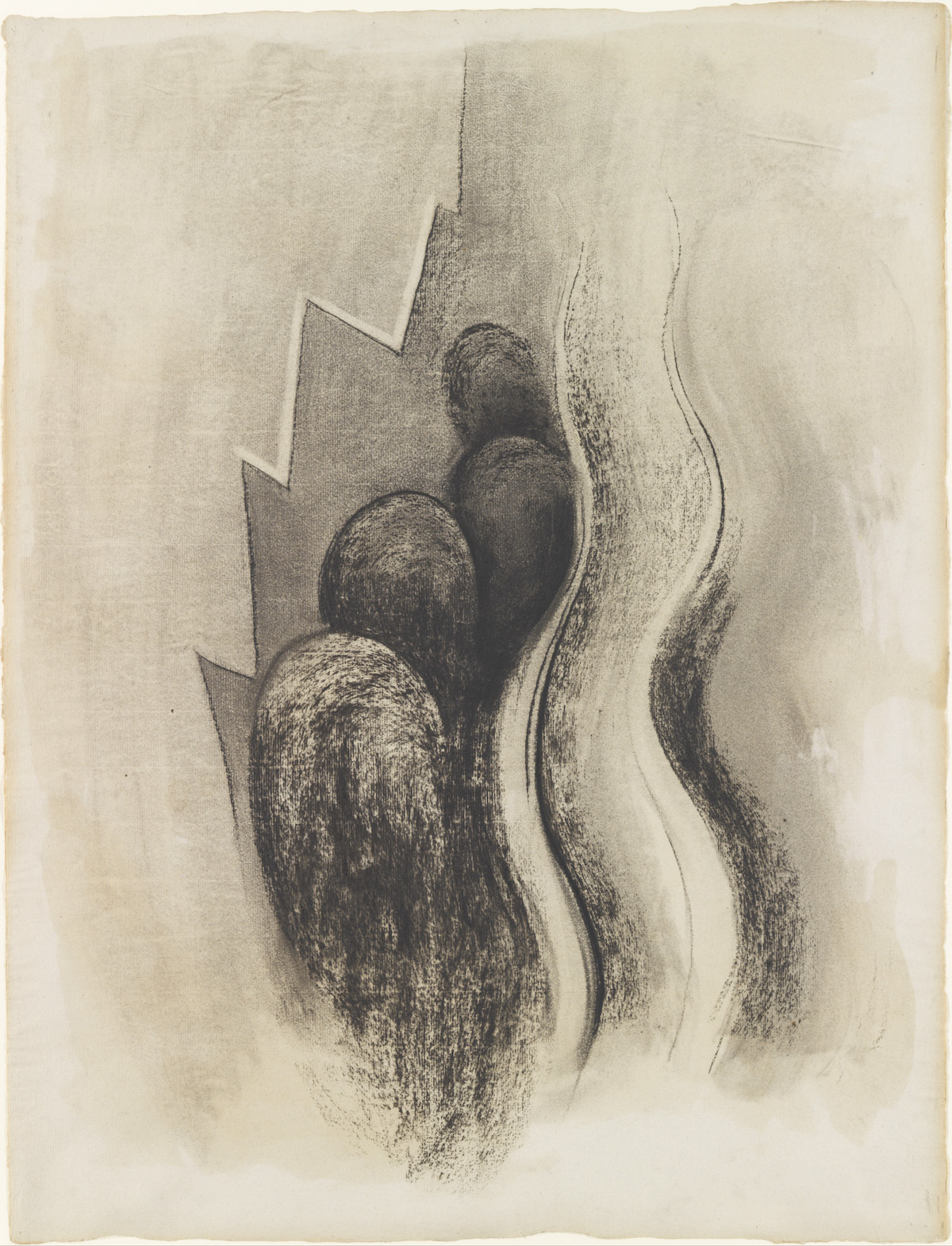

With the DMA, another Texas museum whose foundational moments became quickly intertwined with O’Keeffe’s was the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth. Originally founded in 1961 as the Amon Carter Museum of Western Art, the museum always declared a commitment to defining “western art” in terms beyond the typical cowboy images.7 Though the work of Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell—arguably the quintessential cowboy artists—were at the heart of the private collecting practices of Amon G. Carter Sr., Ruth Carter Stevenson, Board of Trustees president and daughter of Carter, soon began lobbying for the museum to include modern and contemporary art with diverse connections to the West.8 And in that vein, the museum wasted little time preparing an exhibition of 95 of O’Keeffe’s works that opened in 1966. This exhibition illuminated the widest variety of O’Keeffe’s subjects and styles, including flower pictures, Southwest landscapes, iconic Penitente crosses, animal bones, and nearly pure abstractions.9 O’Keeffe also worked directly with the museum staff for years in preparation for this retrospective, and she attended the opening in person.10

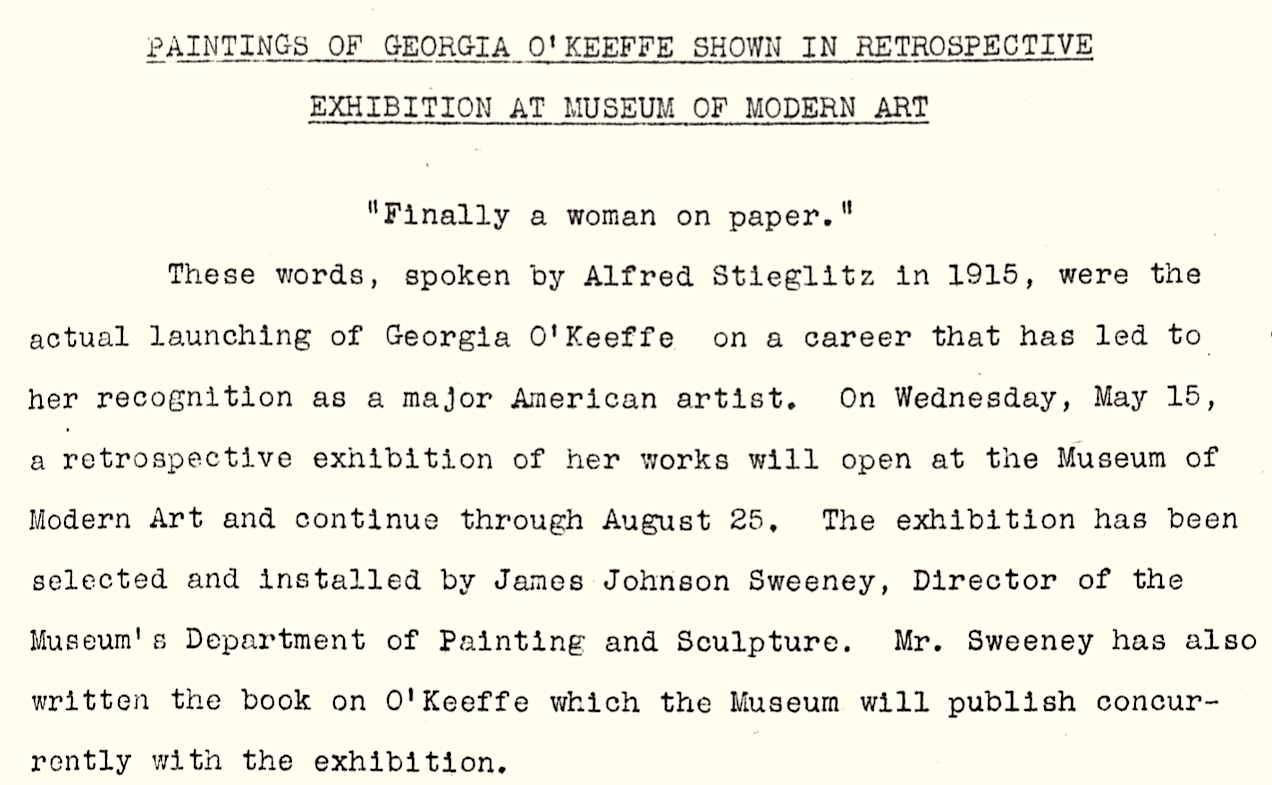

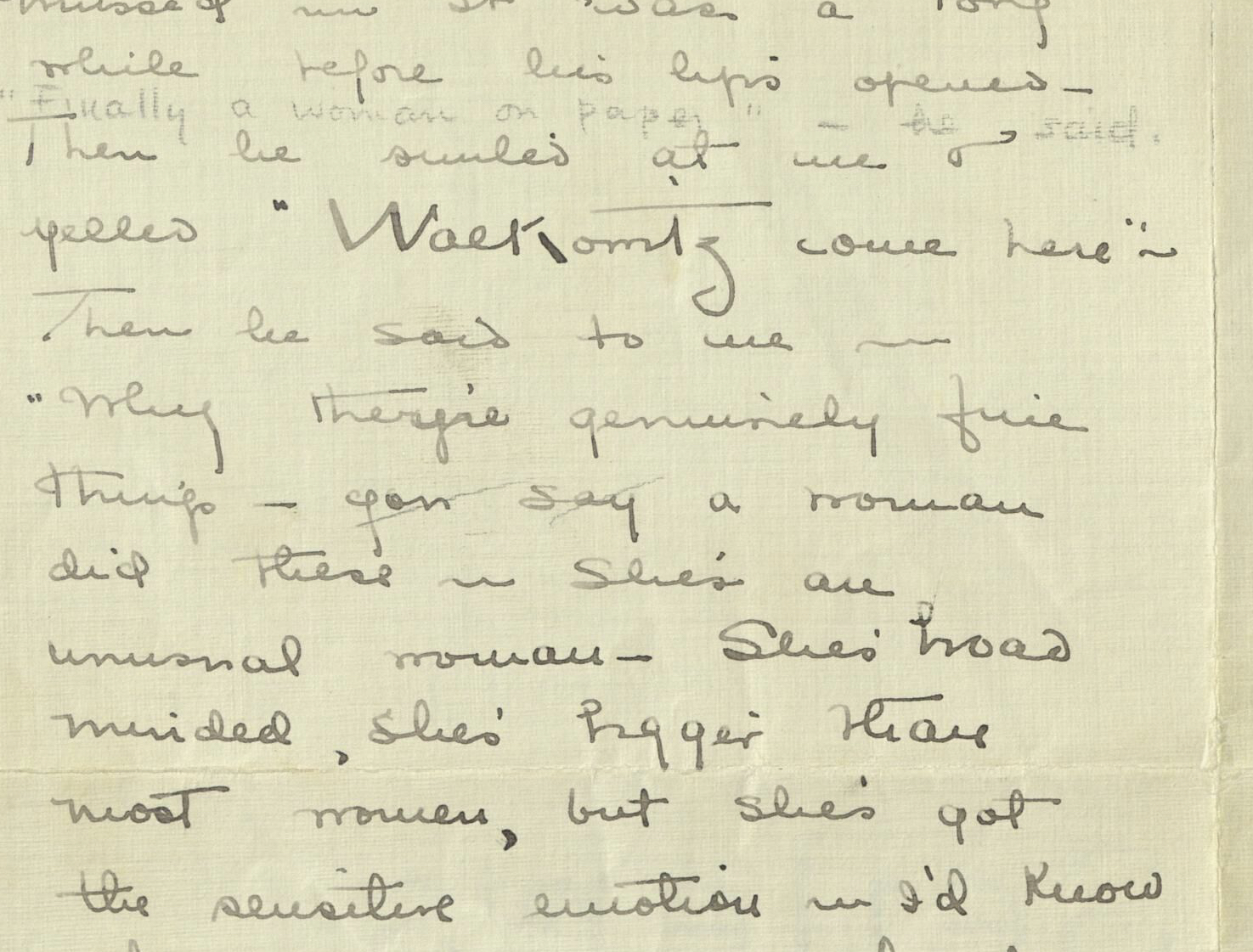

The curator of this O’Keeffe retrospective and the first director of the Amon Carter, Mitchell A. Wilder, was not an O’Keeffe expert, but had a rich understanding of the wide scope of art produced and consumed in the American West.11 Before being hired by the Fort Worth museum, Wilder had become a leading expert on Hispanic colonial art, especially religious folk art of the Southwest, and had served for years as director at the Colorado Springs Fine Art Center, which housed a large collection of Native American art. Wilder was therefore a bold but ideal choice to organize the Amon Carter’s show of O’Keeffe’s work in a way that was declaratively Texan, Western, and “American” at the same time.12 His team of board members at the Amon Carter included other leading art collectors in Texas, such as John de Menil (later a founder of the Menil Collection in Houston; but also Rene d’Harnoncourt, director of MoMA; Richard F. Brown, the first director of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA); and Philip Johnson, the world-renowned architect who designed the Amon Carter building. Wilder also brought on James Johnson Sweeney to install O’Keeffe’s works at the Amon Carter; a longtime friend of the artist, Sweeney had helped curate her retrospective at MoMA and had by then taken the position of director at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.13 Clearly the new art museum in Fort Worth was thinking beyond Texas and beyond any limited “regional” scope.

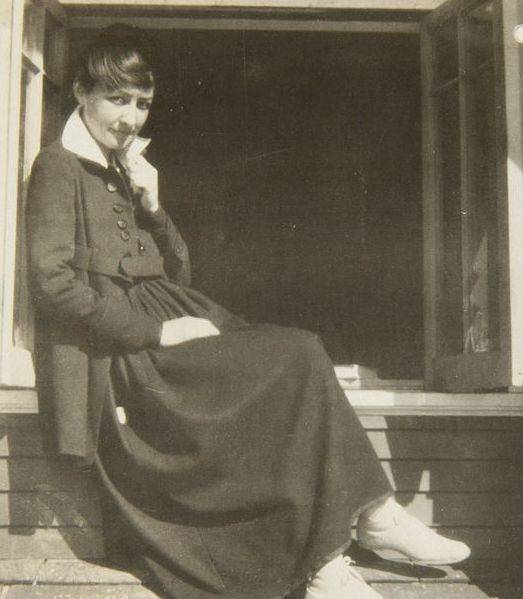

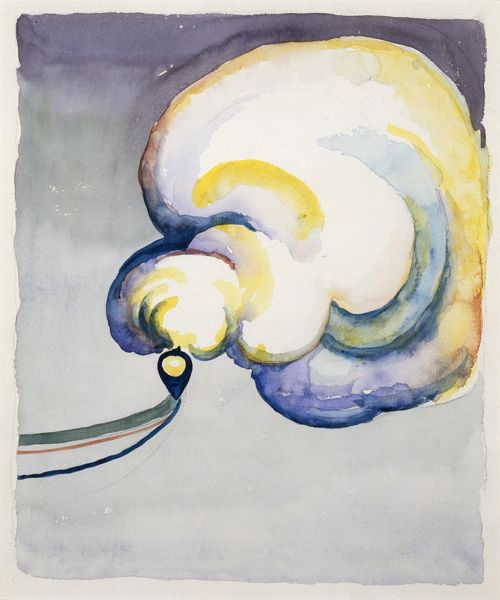

The cover of the exhibition catalogue of O’Keeffe’s Amon Carter retrospective was also an interesting choice—one that reveals the museum’s desire to highlight the artist’s latest forays into extreme abstraction, rather than feature her more recognizable subjects. The cover shows the stark design of Winter Road I (1963, figure 3), painted just three years before the opening of the exhibition, where a warm brown, calligraphic line dances in a curve across the space against an open and empty white ground. This minimalist image fits well within the art trends of the 1960s, when abstraction in the United States had shifted from abstract expressionist, rather busy “allover” compositions to more subdued geometric styles.14 Featuring this painting on the catalogue cover—an abstract design based directly on the artist’s view of a road curving around a mesa as seen out of her bedroom window in Abiquiú, New Mexico, which would not have been obvious to many viewers15—demonstrates the curators’ wishes to declare O’Keeffe’s continued modernity and contemporary relevance in a changing art world. And by 1967, the year after the O’Keeffe retrospective, Stevenson publicly declared the Amon Carter’s new mission to expand their purview to focus on “American art” broadly conceived.16 Though it took until 2010 for the museum to officially change its name to the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, this expanded mission was arguably catalyzed by the O’Keeffe show in 1966.17

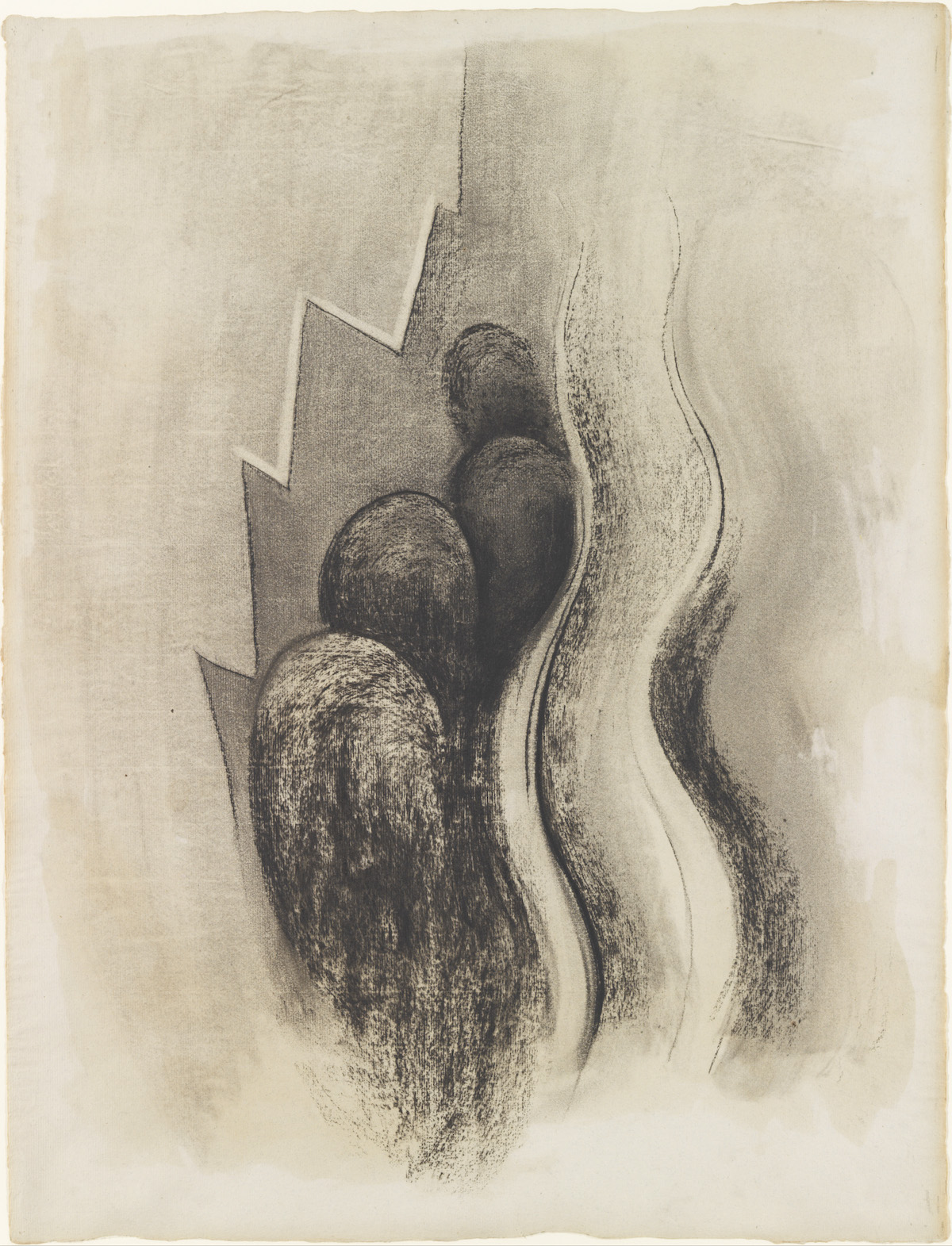

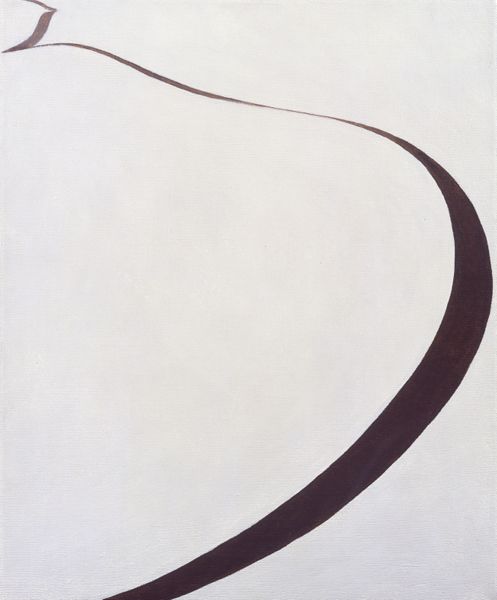

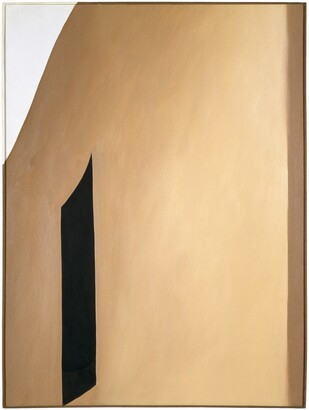

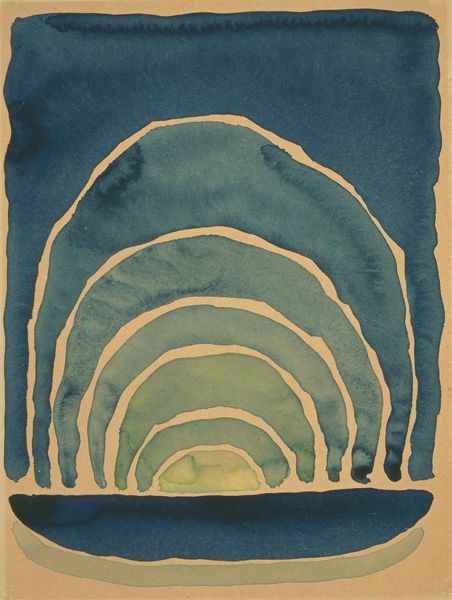

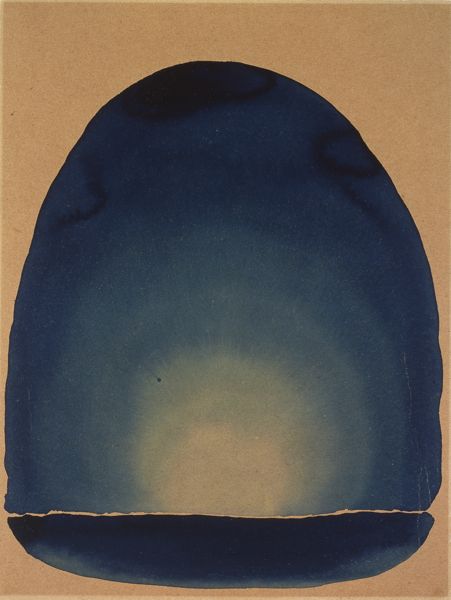

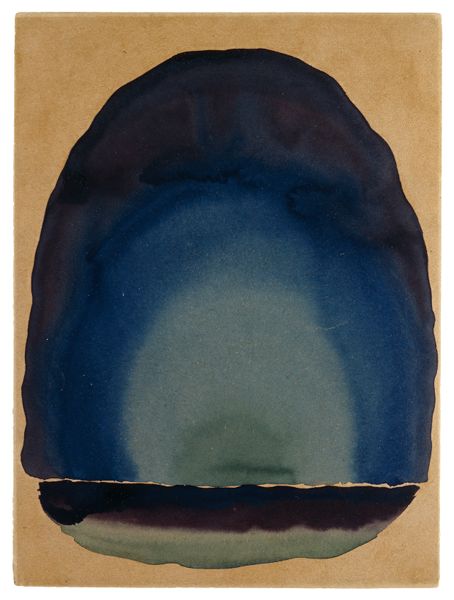

Another intriguing fact about O’Keeffe’s Winter Road I is that the Amon Carter described the painting in 1966 as newly part of its permanent collection, listing it as such in the exhibition catalogue, for instance.18 Along with the major works that the museum acquired by the artist—Dark Mesa with Pink Sky (1930, figure 4), acquired in 1965; and Black Patio Door (1955, figure 5) and the three-part watercolor series Light Coming on the Plains (No. I, No. II, and No. III) (1917, figures 6–8), all acquired in 1966—Winter Road I would have been a major coup for the museum to have in its collection. However, the painting did not stay at the Amon Carter, and since 1995 has been in the National Gallery of Art’s collection in Washington, DC.19

But even without the retention of this boldly abstract piece, the Amon Carter still solidified a premier collection of O’Keeffe works in the context of her 1966 retrospective. In particular, the Amon Carter was among the first institutions to recognize the artist’s Texas period as both unique and significant. Acquiring the Light Coming on the Plains series brought some of the first major Texas works out from the artist’s personal collection and into a public museum. The majority of O’Keeffe’s Texas watercolors remained with the artist until her death, and are now in the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe.20 And the few Texas pieces by O’Keeffe that have now made their way back to the state—such as an Evening Star at the McNay, acquired in 1985 (figure 9), and the four pieces at the Amarillo Museum of Art, including a beautiful image of a train in the distance (figure 10), acquired in 1982—arrived decades after the Amon Carter acquired their Texas watercolor gems, around the death of O’Keeffe, who passed in 1986.21

The McNay Museum in San Antonio has also long committed to showing and supporting O’Keeffe’s work. The McNay opened its doors in 1954, and by 1958 was featuring several major works by the artist in a show titled American Art in San Antonio.22 Two of these pieces, From the Plains I / From the Plains (1953, figure 11) and Goat’s Head (1957, figure 12), were part of the private collection owned by San Antonio millionaire Tom Slick, an inventor who was the son of one of the most successful Texas oilman “wildcatters,” whose tagline became “slick ideas.”23 According to his niece, who penned his biography, “whether [Tom] was pursuing the Yeti, or a cure for cancer, or a new oil recovery technology, or the best food in town, [he] was passionately awake and present, never numb.”24 That passion for discovery led Slick to invest in innovative modern art, including works by O’Keeffe. Both From the Plains I and Goat’s Head were later donated to the McNay from the Slick Estate in 1973, and today remain in the museum’s permanent collection.25

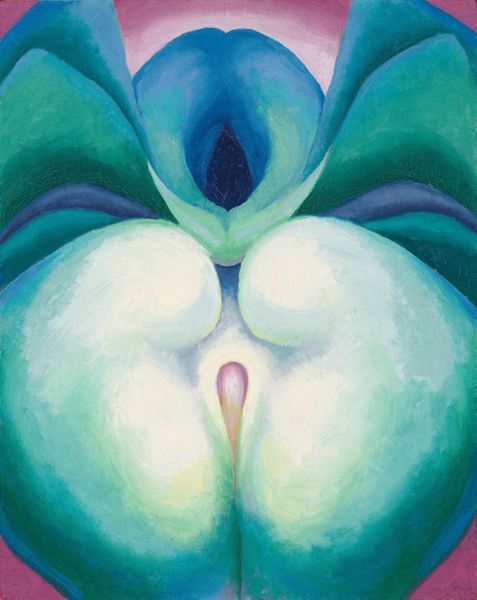

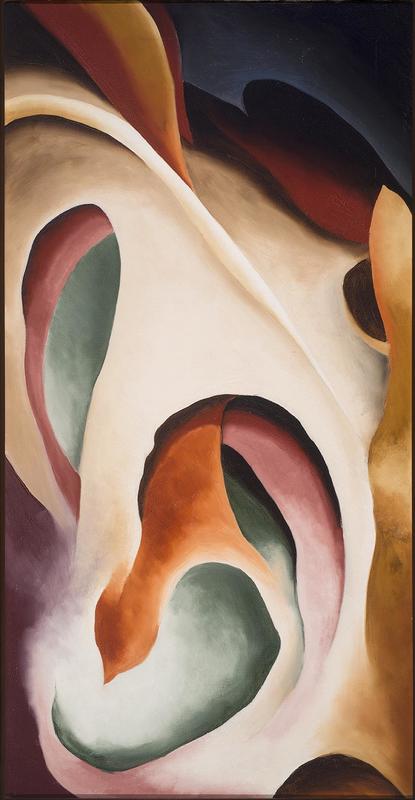

After its initial decade, the McNay continued to dedicate exhibitions to O’Keeffe’s work, including one in 1960; a solo show of the artist’s work in 1975, which resulted in the museum’s acquisition of the stunning abstraction Leaf Motif, no. 2 (1924, figure 13); and the important O’Keeffe and Texas in 1998, for which leading O’Keeffe scholar Sharyn Udall conducted significant research on the artist’s Texas years and authored an extensive catalogue.26 Unfortunately, this show included more than two dozen of the “Canyon Suite” watercolor series, now shown to be fakes.27 The series had been “discovered” in the town of Canyon just after the death of O’Keeffe, had been bought and sold on the market, and wound up in the collection of Crosby Kemper of Kansas City, who loaned it to the McNay for the 1998 show. Only after the 1999 catalogue raisonné of O’Keeffe’s work was published did the inauthenticity of the watercolors become public, and Kemper demanded a refund from his dealer on his multimillion-dollar purchase of the works.28 This scandal, however, did not stop the McNay from continuing to feature exhibitions of the artist’s work, and in 2022 the museum hosted Georgia O’Keeffe and American Modernism.29

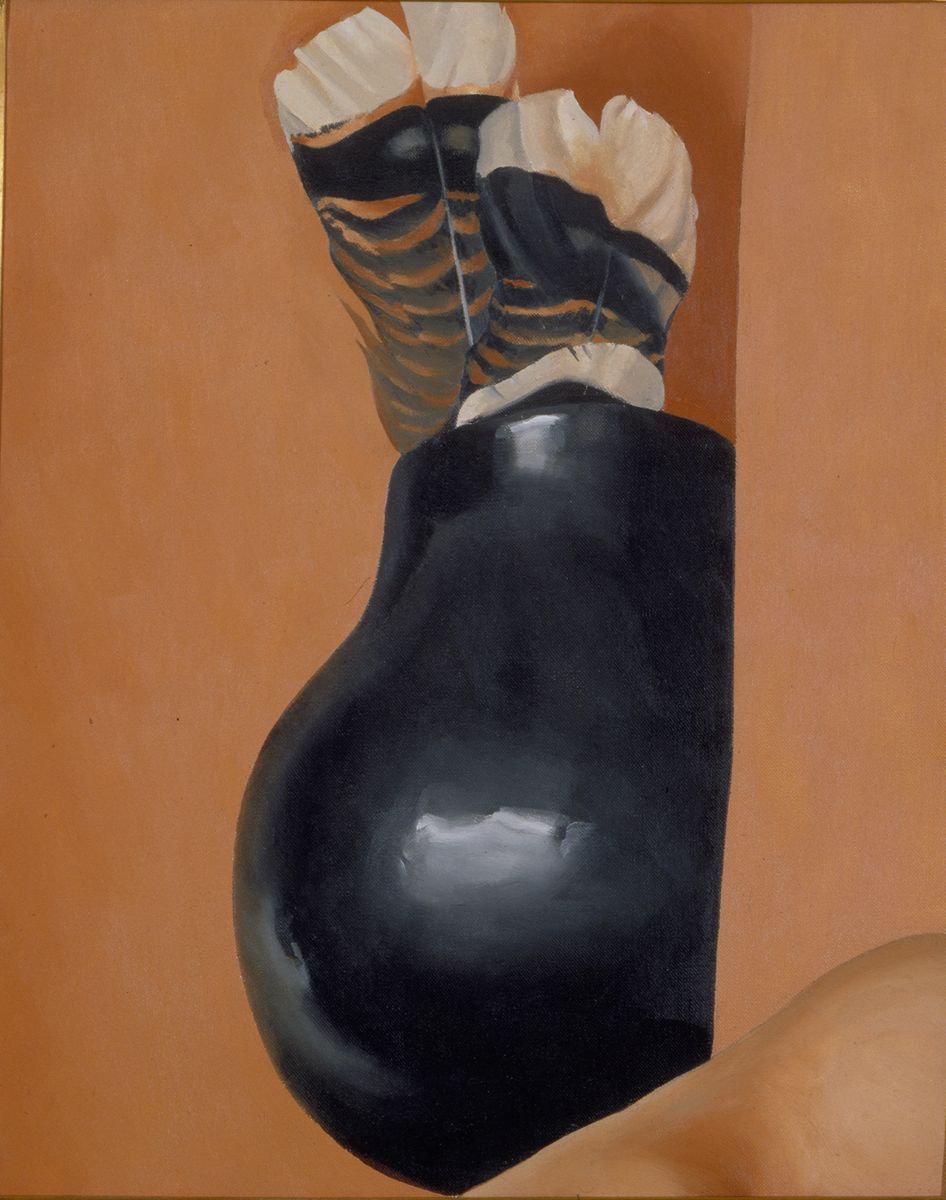

Perhaps one of the collectors most critical to O’Keeffe’s connection to Texas is Anne Marion, the Fort Worth–born heiress of an oil and ranching fortune. Marion became a major benefactor of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth in the early 1980s, and then founded the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe in 1997—the first U.S. museum dedicated to a single woman artist.30 But even as early as the 1966 retrospective at the Amon Carter, Marion was loaning O’Keeffe’s art from her private collection to be seen by a Texas public. For instance, she loaned Pelvis Series, Red with Yellow (1945, figure 14) to the Fort Worth museum before later placing it on extended loan to the O’Keeffe Museum. In other words, Marion was utterly instigative in supporting the Texan legacy of O’Keeffe.

According to the Dallas Museum of Art website, “Georgia O'Keeffe was truly an artist of this region, but moreover she was a true American icon and a sure favorite with the public.” This binary of regional and national, Texan and American, was at the heart of O’Keeffe’s Texas exhibitions. Not only was the artist’s reputation significantly enhanced by the attention she received in Texas, but the museums and collectors of Texas have gained national clout in their choice to put O’Keeffe’s art on display again and again.

Notes

Note on titles of works: Institutional titles and dates for O’Keeffe’s works sometimes vary from first titles and dates established by Georgia O’Keeffe: Catalogue Raisonné (1999), whose entries explain changes. Here institutional titles and dates are listed first followed by those in the Catalogue Raisonné.

-

Her life and work in New Mexico has been extensively documented. A good place to start is Barbara Buhler Lynes and Agapita Judy Lopez, Georgia O’Keeffe and Her Houses: Ghost Ranch and Abiquiu (New York: Abrams; Santa Fe, NM: The Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, 2012). On her time in Texas, see especially Amy Von Lintel, Georgia O’Keeffe’s Wartime Texas Letters (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2020); and Georgia O’Keeffe and Amy Von Lintel (text author), Georgia O’Keeffe Watercolors, 1916-1918 (Santa Fe, NM: Radius Books and the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, 2016). ↩︎

-

See Eileen Kinsella, “O’Keeffe Painting Sells for $44 Million at Sotheby’s, Sets Record for Work by Female Artist,” Artnet, November 20, 2014, https://news.artnet.com/market/okeeffe-painting-sells-for-44-million-at-sothebys-sets-record-for-work-by-female-artist-176413. ↩︎

-

The name changed to the Dallas Museum of Art in 1984. The majority of the 29 paintings in this 1953 exhibition were lent to the Dallas museum by Edith Halpert’s Downtown Gallery in New York City, and only included works from 1924 to 1950. In other words, there were no works from her Texas years. Moreover, the biographical summary given in the exhibition catalogue mentioned O’Keeffe’s work as a “high school teacher” in Amarillo but said nothing about her time teaching at West Texas State Normal College (now West Texas A&M University) in Canyon from 1916 to 1918, when she produced dozens of paintings and drawings. Instead, it says she “came to New York in 1915 and lived there until 1949,” misrepresenting how nomadic she actually was in these years. See An Exhibition of Paintings by Georgia O’Keeffe, online at the “The Portal to Texas History” as part of the DMA exhibition records: https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth183370/m1/3/. ↩︎

-

On the Art Institute of Chicago exhibition, see the digitized version of the catalogue by Daniel Catton Rich: https://www.artic.edu/exhibitions/7588/retrospective-exhibition-of-paintings-by-georgia-o-keeffe. Though no works from Texas were included in the Chicago exhibition, the catalogue includes a section on O’Keeffe’s time in and inspiration from Texas. The MoMA retrospective did not include a catalogue publication, and likewise no Texas works were included. See https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2851.

On the history of the DMA, see the museum website: https://dma.org/about/museum-history. According to the museum, the Centennial Exposition Art Exhibition drew more than 154,000 visitors to the new building from June 6 to November 26, 1936—visitors who would have viewed O’Keeffe’s works on display there. ↩︎

-

The exhibitions at the DMA that featured O’Keeffe included, in addition to the 1936 and 1953 shows, a group show on religious art in 1958; Southwestern Art: A Sampling of Contemporary Painting and Sculpture, 1960; Dallas Collects, 1963; Georgia O’Keeffe, 1887-1986, 1988, which traveled to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, the Art Institute of Chicago, and The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York; and Georgia O’Keeffe: The Poetry of Things, organized by the DMA and the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC, in 1999. The 1988 retrospective had a record 205,904 visitors, with 24,000 attending the first week alone. ↩︎

-

Texas museums not discussed in this essay that also have works by O’Keeffe include the Museum of Texas Tech University, which has Red Hills, Series II-35 (1938); the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum in Canyon, which has Red Landscape (1917); and the Stark Museum of Orange, which has Gerald’s Tree II (1937). The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has three of O’Keeffe’s paintings, all acquired after 1970. ↩︎

-

The Amon Carter’s early mission statement is worth quoting in full: “The Amon Carter Museum of Western Art was established under the will of the late Amon G. Carter for the study and documentation of westering North America. The program of the Museum is expressed in publications, exhibitions, and permanent collections related to the many aspects of American culture, both historic and contemporary, which find their identification as Western.” See Mitchell A. Wilder, ed., Georgia O’Keeffe: An Exhibition of the Work of the Artist from 1915 to 1966 (Fort Worth, TX: Amon Carter Museum of Western Art, 1966), copyright page. ↩︎

-

See the Amon Carter Museum website: https://www.cartermuseum.org/about/our-story. ↩︎

-

The catalogue presented a unique but highly effective method of showing this range of production. The text drew from exhibition reviews and writeups across the career of O’Keeffe, beginning with Marsden Hartley’s catalogue foreword in 1935 and ending with Sam Hunter’s catalogue foreword for a show at Brandeis University in 1963. These previously published statements about O’Keeffe’s work highlight everything from her earliest abstractions, to her New York City pictures, to her bone and cross series, to her nature paintings. Though many of them are very stereotypical in their gendered assessment of O’Keeffe and her work, they are also highly illuminating for the ongoing reception of her abstract style, including the 1963 essay by Hunter that argues for O’Keeffe’s unique “experiential” mode of abstraction that places her squarely in minimalist and post-modern trends. ↩︎

-

Wilder, Georgia O’Keeffe, foreword. ↩︎

-

Wilder was the director of the Amon Carter Museum in 1966, but he was largely responsible for the organization of the exhibition. Sweeney “installed the exhibition” at the request of O’Keeffe. See Wilder, Georgia O’Keeffe, foreword. The exhibition also traveled to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. ↩︎

-

On Wilder’s awareness of the particularly layered and complicated role of a curator in a western U.S. museum like the Amon Carter, see Mitchell A. Wilder, “Art in the Southwest,” The Atlantic, March 1951, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1951/03/art-in-the-southwest/639730/. He particularly highlighted the importance and growth of Texas museums. ↩︎

-

On O’Keeffe’s friendship with Sweeney, see, for instance, Georgia O’Keeffe to Ted Reid, postmarked May 10, 1946, Ted Reid-Georgia O’Keeffe Archive, Cornette Library, West Texas A&M University. The letter describes a party that Sweeney was throwing O’Keeffe at his home following the opening of her retrospective at MoMA. She refers to “my friends the Sweeneys.” ↩︎

-

For a good definition of abstract expressionism, see the MoMA website: https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/themes/abstract-expressionism/. ↩︎

-

On this view and its relationship to the painting, see the polaroid taken by O’Keeffe (https://collections.okeeffemuseum.org/object/6015/) as well as Lynes and Lopez, O’Keeffe and Her Houses, 242–47. O’Keeffe wrote: “Two walls of my room in the Abiquiu house are glass and from one window I see the road toward Española, Santa Fe, and the world. The road fascinates me with its ups and downs and finally its wide sweep as it speeds toward the wall of my hilltop to go past me.” ↩︎

-

See the Amon Carter Museum website: https://www.cartermuseum.org/about/our-story. ↩︎

-

The museum dropped the “of Western Art” designation in its title in 1977 and added “of American Art” in 2010. See https://www.cartermuseum.org/about/our-story. ↩︎

-

Wilder, Georgia O’Keeffe, copyright page, 30. ↩︎

-

See https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.91449.html. The reasons why the painting did not remain at the Amon Carter Museum are still unclear, per email correspondence between the author and Jonathan Frembling on August 30, 2022. ↩︎

-

See Barbara Buhler Lynes and Russell Bowman, O’Keeffe’s O’Keeffes: The Artist’s Collection (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2001). ↩︎

-

Amarillo as a city has long had its eye on O’Keeffe as part of their artistic claims to fame, given that the artist lived and taught school there between 1912 and 1914. In 1968, the Junior League of Amarillo organized an exhibition of the artist’s work held at the Amarillo Civic Center, and then the Amarillo Art Center (now Amarillo Museum of Art, a name change that occurred in 1994) organized a group show in 1985. See Al Kochka et al., Georgia O’Keeffe and Her Contemporaries (Amarillo, TX: Amarillo Art Center, 1985). This show included 24 of O’Keeffe’s works, including early abstractions, Texas watercolors, as well as flower, shell, landscape, and bone paintings. Later acquisitions of O’Keeffe’s work at the Amon Carter include Red Cannas (1927) in 1986; Series I, No. 1 (1918) in 1995; and White Birch (1925) in 1997. See https://www.cartermuseum.org/collection/red-cannas-198611, https://www.cartermuseum.org/collection/series-i-no-i-19958, and https://www.cartermuseum.org/collection/white-birch-19977a. White Birch was featured in the 1966 retrospective at the Amon Carter, on loan from the private collection of Mr. and Mrs. J. Lee Johnson III of Fort Worth. See Wilder, Georgia O’Keeffe, 28. ↩︎

-

On the history of the McNay, see the museum website: https://www.mcnayart.org/our-mission/. ↩︎

-

In Texas, a “wildcatter” is someone who drills for oil in places not known to have deposits, in other words, high-risk, exploratory drilling. ↩︎

-

Elaine Wolff, “In Search of Tom Slick, Art Collector,” San Antonio Current, June 17, 2009, https://www.sacurrent.com/arts/in-search-of-tom-slick-art-collector-2286290. This article was published in the context of an exhibition on the Slick art collection at the McNay. See also Catherine Nixon Cooke, Tom Slick: Mystery Hunter (n.p.: Paraview, 2005); In Search of Tom Slick: Explorer and Visionary, rev. ed. (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2020); and Loren Coleman, Tom Slick: True Life Encounters in Cryptozoology (Fresno, CA: Craven, 2002); as well as the biographical statement on Slick featured on the Christie’s auction house webpage on O’Keeffe’s Sun Water Maine pastel from 1922, which was in Slick’s collection: https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5631570. ↩︎

-

From the Plains I was also included in the 1966 retrospective at the Amon Carter. ↩︎

-

Sharyn Udall, O’Keeffe and Texas (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1998). This show also led to the McNay’s acquisition of O’Keeffe’s Pink and Yellow Hollyhawks (1952). See https://collection.mcnayart.org/objects/6199/pink-and-yellow-hollyhocks. ↩︎

-

The scandal of the “Canyon Suite” fakes was extensively covered in the press in the late 1990s and early 2000s. See, for instance, Jo Ann Lewis, “The Curious Case of the Spurious O’Keeffes,” Washington Post, August 6, 2000; Jo Ann Lewis, “The Art that Went from Boon to Bust,” Washington Post, December 3, 1999, C1; and Gretchen Reynolds, “If It’s Not an O’Keeffe, Exactly What Is It?,” New York Times, March 7, 2000. For more of an assessment of the crime and its context in Canyon, Texas, see Amy Von Lintel, “A Famous Art Fraud Demystified,” Panhandle Art Stories (Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, forthcoming). ↩︎

-

Barbara Buhler Lynes, Georgia O’Keeffe: Catalogue Raisonné (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1999). Lynes and National Gallery Paper Conservator, Judith C. Walsh, discovered that some of the “Canyon Suite” works were produced after O’Keeffe was teaching at West Texas State Normal College, and none was on the type of paper O’Keeffe used for more than 95% of the watercolor paintings she produced during her tenure there. ↩︎

-

See https://www.mcnayart.org/exhibition/okeeffe-and-american-modernism/. ↩︎

-

Anne Burnett Windfohr Marion was born in 1938. Her father Samuel Burk Burnett was the founder of 6666 Ranch in King County and became one of the wealthiest men in Texas. On Marion, see Tessa Solomon, “Anne Marion, Founder of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in New Mexico, Has Died at 81,” ArtNews, February 13, 2020, https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/anne-marion-died-at-81-1202677880/; and Katharine Q. Seelye, “Anne Marion, Texas Rancher, Heiress and Arts Patron, Dies at 81,” New York Times, February 25, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/25/us/anne-marion-dead.html. ↩︎