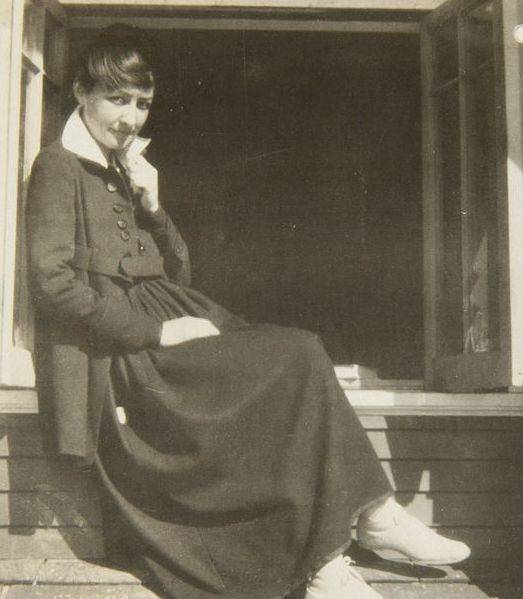

In 1927, artist and critic Frances O’Brien visited her friend Georgia O’Keeffe on the 28th floor of the Shelton Hotel. O’Brien observed the painter in her element, working quietly in the apartment she shared with her husband and promoter, the photographer Alfred Stieglitz. The result of O’Brien’s visit was a richly detailed, if brief, profile of O’Keeffe featured in a series of “Personality Portraits” called Americans We Like for the progressive biweekly magazine The Nation. In the piece, O’Brien noted that “Georgia O’Keeffe has never allowed her life to be one thing and her painting another” and offered up a series of incisive observations about the painter’s looks, clothes, and lifestyle.1

O’Brien’s article was hardly the first to emphasize O’Keeffe’s physical and social identity in addition to her artwork; rather, it reflects a widespread tendency on the part of critics and the public to connect O’Keeffe’s work to other elements of her life, something that permeates much of past and present scholarship on the artist. An avowed individualist, O’Keeffe’s dress, relationships, and style of living set her apart from other women of the time and invited this sort of interpretation. It also contributed to the formation of a cult of personality that fuels her continued mythologization.2 This phenomenon has outlasted O’Keeffe herself—it appears even in more recent retrospectives of the artist: A 2000 exhibition at the Phillips Collection featured massive black-and-white photographs of the artist and her living space in conjunction with paintings of objects in her home. The Brooklyn Museum’s 2017 show Living Modern displayed images of O’Keeffe as well as her personal effects side-by-side with her artworks.3

This cult of personality, a force that has so thoroughly shaped O’Keeffe’s image as an artist, coalesced quite early in her career—as early as 1917 and 1923, the dates of her first and second solo exhibitions. Reviews of her shows, profiles such as O’Brien’s, and public reception of her work combined to bring O’Keeffe a kind of notoriety that would set the tone for the rest of her career. This fame was the result of Stieglitz’s mythmaking, O’Keeffe’s own deliberate forms of self-fashioning, and the various early critical and public response to her emergence as an artistic force, which confounded, and occasionally pleased, both O’Keeffe and Stieglitz.

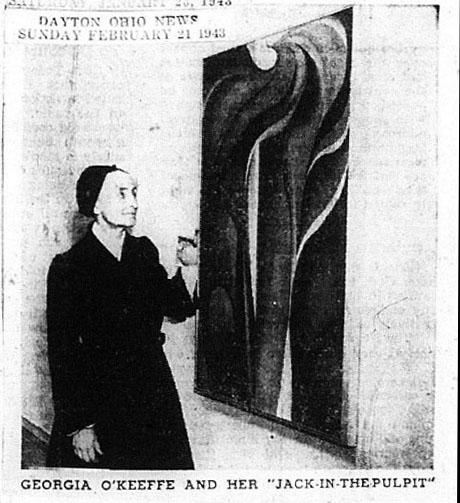

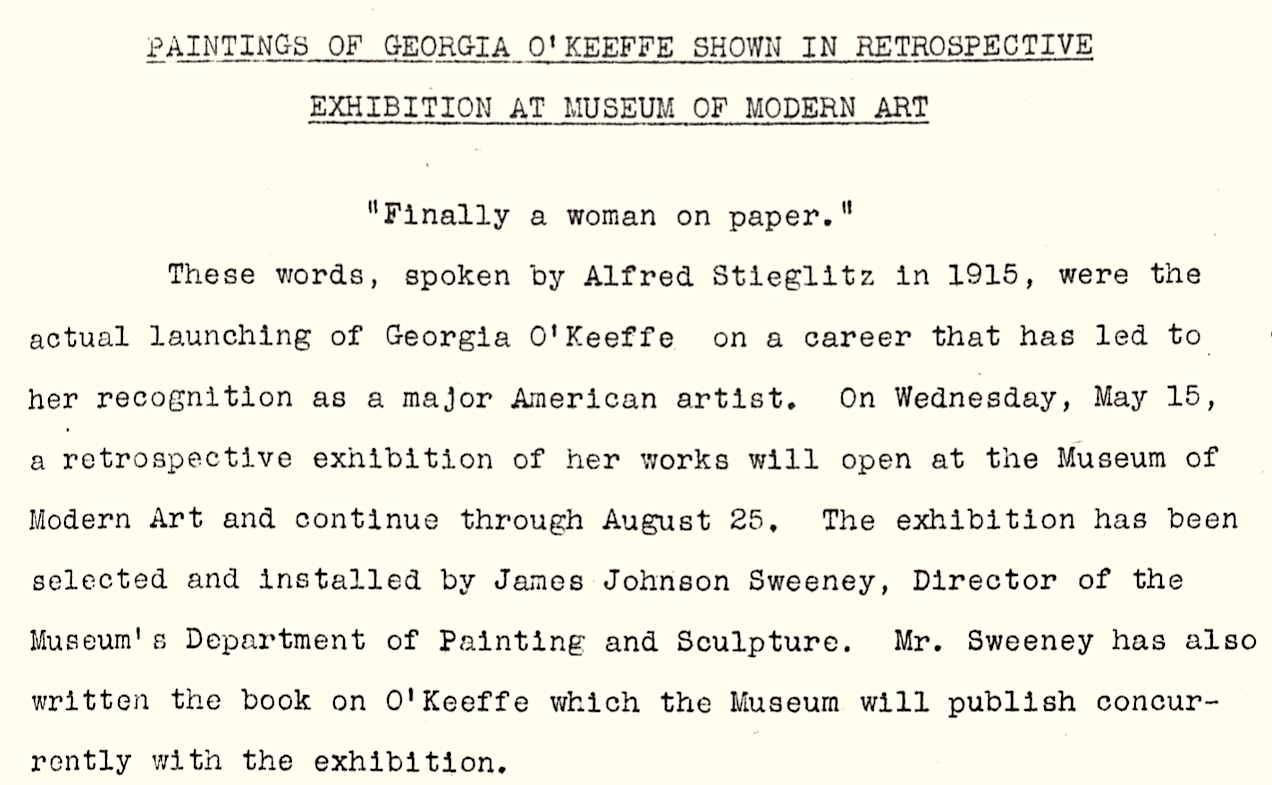

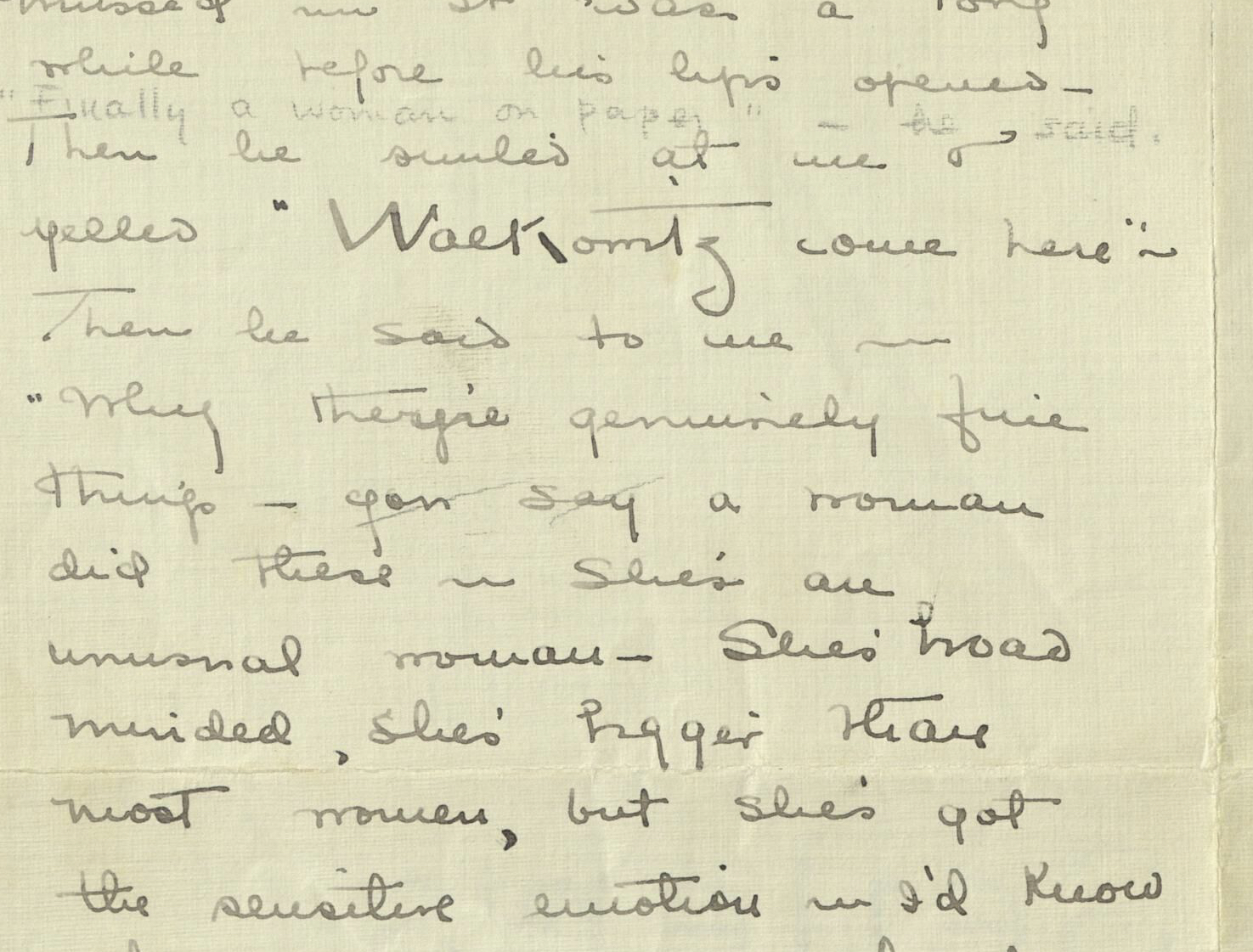

Stieglitz’s promotion of O’Keeffe began in earnest in 1915, when her friend Anita Pollitzer showed Stieglitz a few of the artist’s drawings. His alleged reaction—“finally, a woman on paper!”—has become part of the mythology of O’Keeffe and of her relationship with Stieglitz.4 Though in recent years the truth of this account has come into question, outlined in the essay by Barbara Buhler Lynes, it persists because it reflects Stieglitz’s future treatment of O’Keeffe’s public persona.5 Acting as mentor, professional manager, and, eventually, romantic partner to O’Keeffe, Stieglitz encouraged both the public and the critics to examine the painter’s work through the lens of her personal identity, with particular focus on two elements: her gender and her nationality.

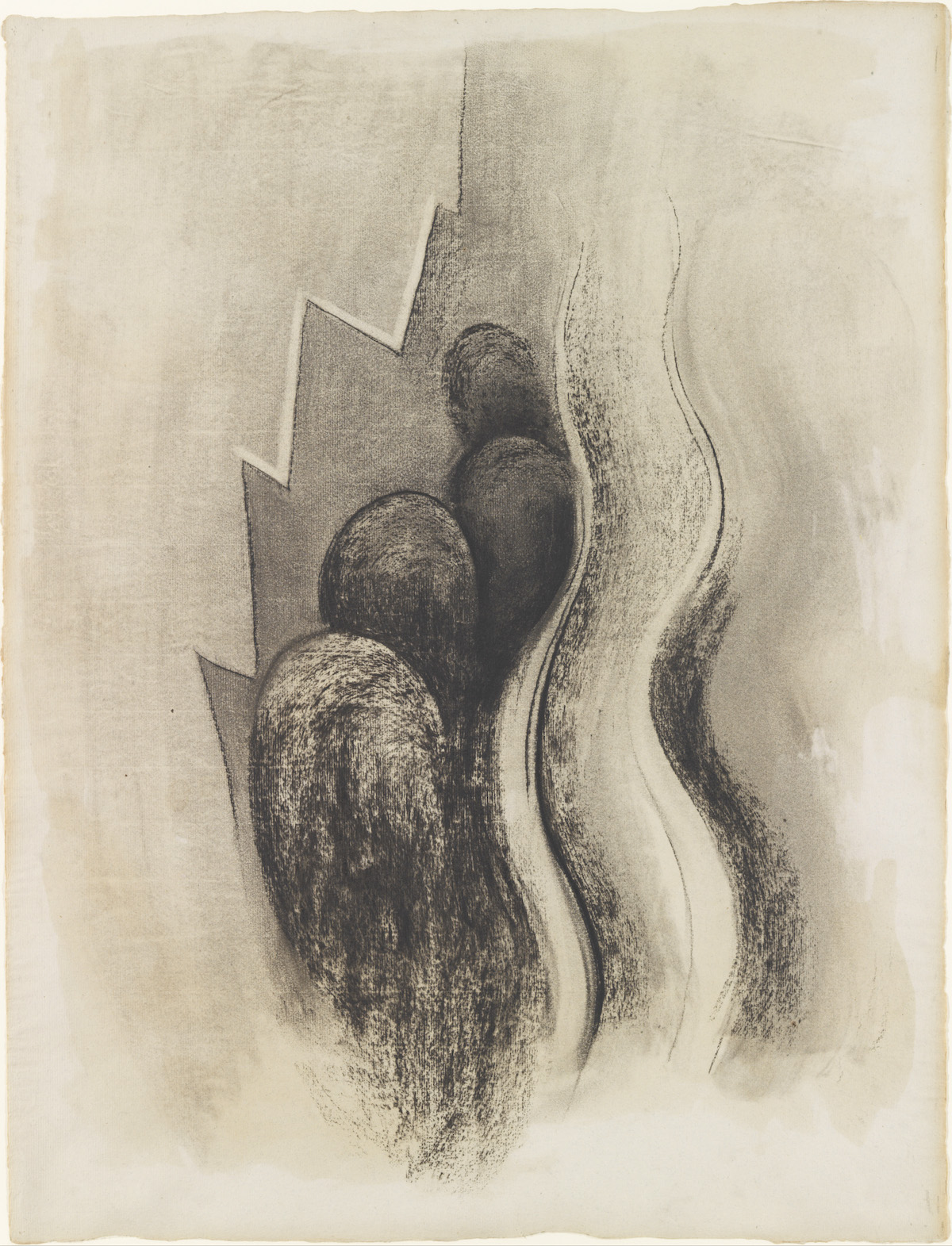

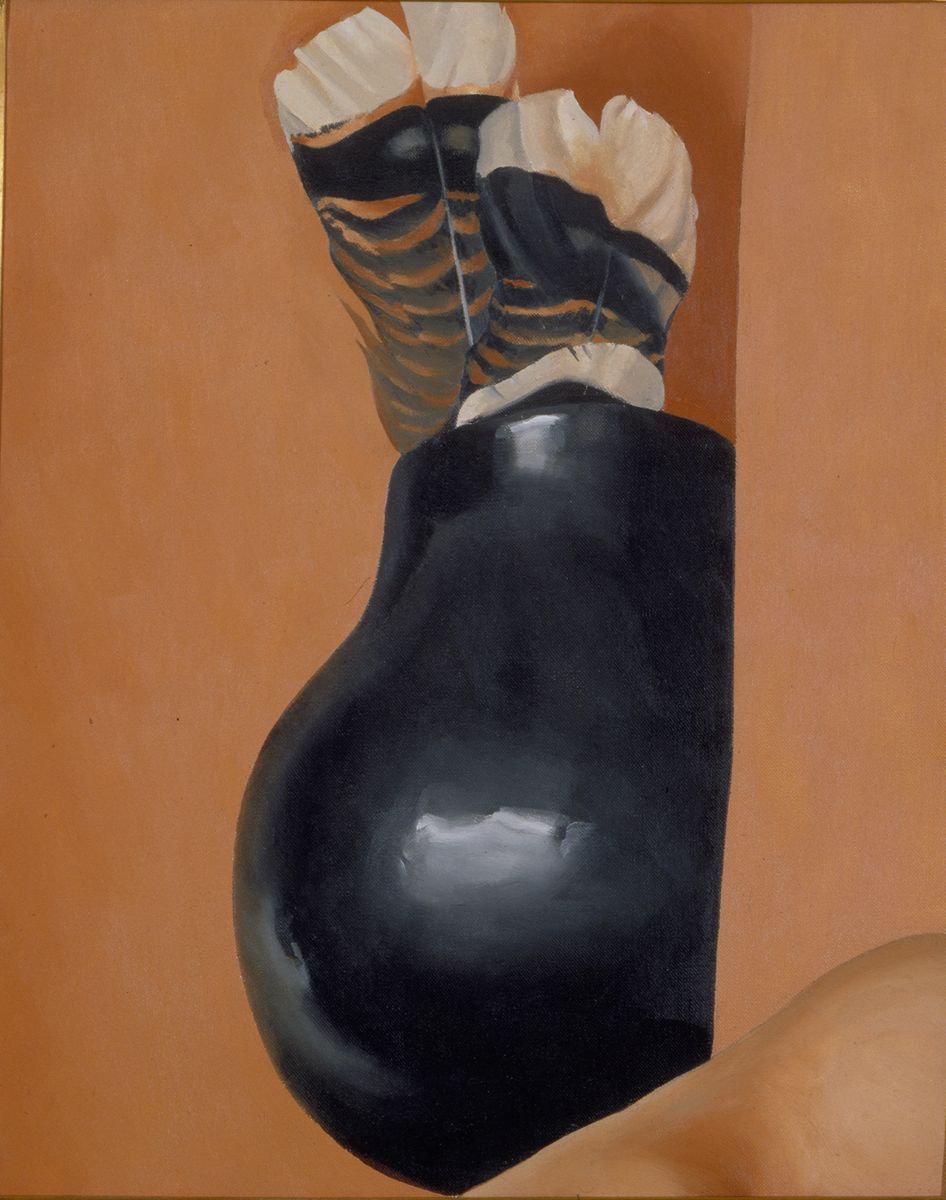

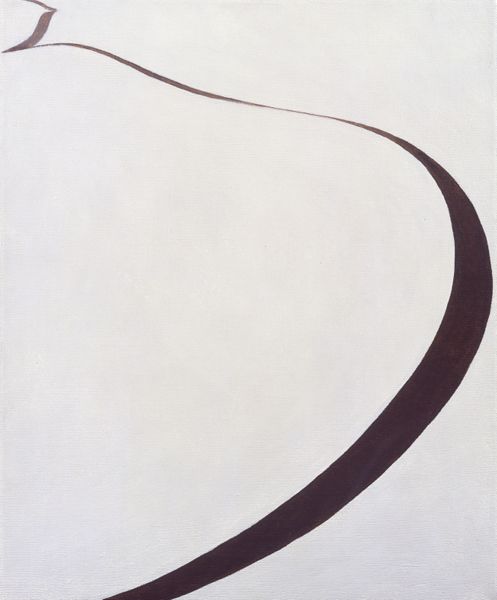

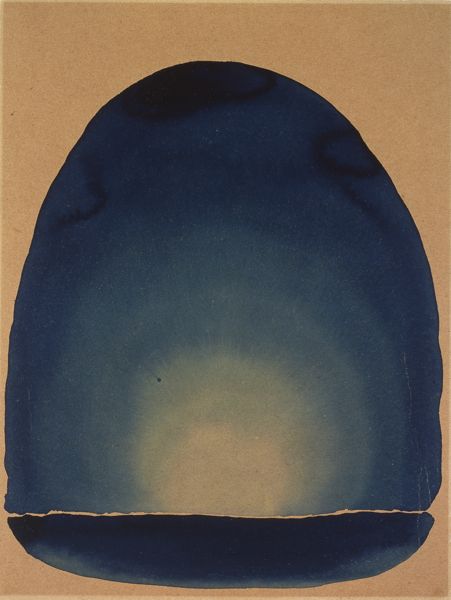

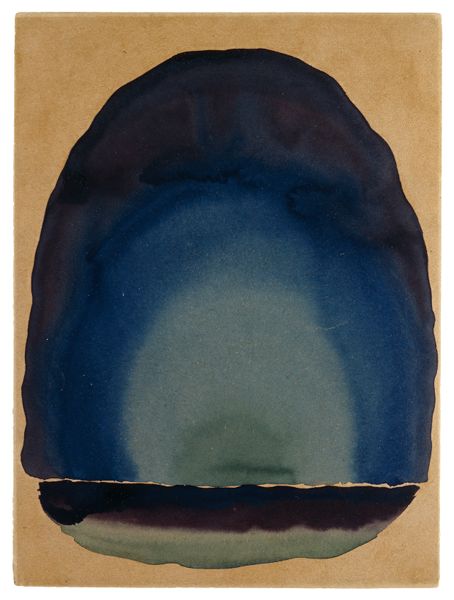

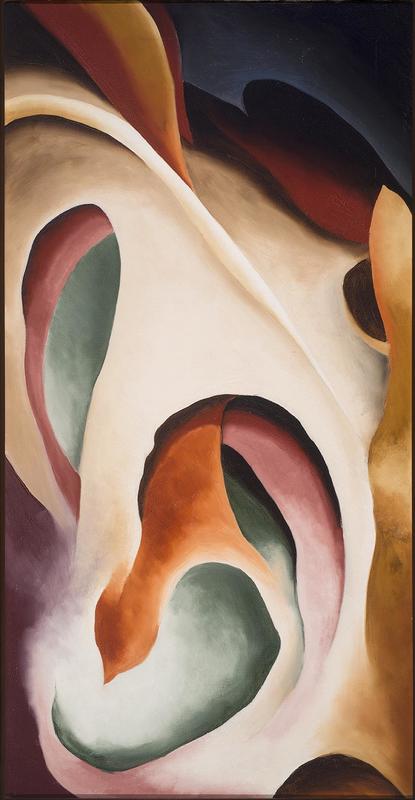

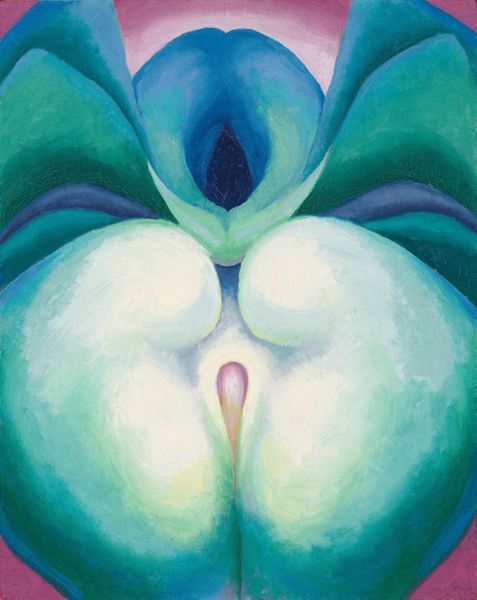

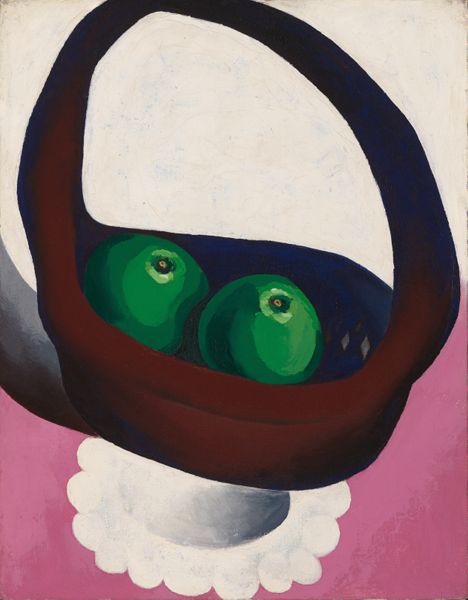

Stieglitz began showing O’Keeffe’s work at his 291 gallery in 1916 and later at Anderson Galleries in New York. The photographer was a self-proclaimed “feminine feminist”—he believed that there were essential and irreconcilable differences between men and women, and that these differences were reflected in their art.6 He had a hyper-idealized concept of woman; in Pollitzer’s words, he was a “composite of the romantic heroines of Wagner and of Goethe . . . and [held] a personal belief in what modern woman could accomplish.”7 O’Keeffe’s early work corresponded with Stieglitz’s notions of womanhood. Her paintings of flowers, a stereotypically feminine subject, evoked the forms of the female body for viewers, critics, and Stieglitz himself (figure 2).

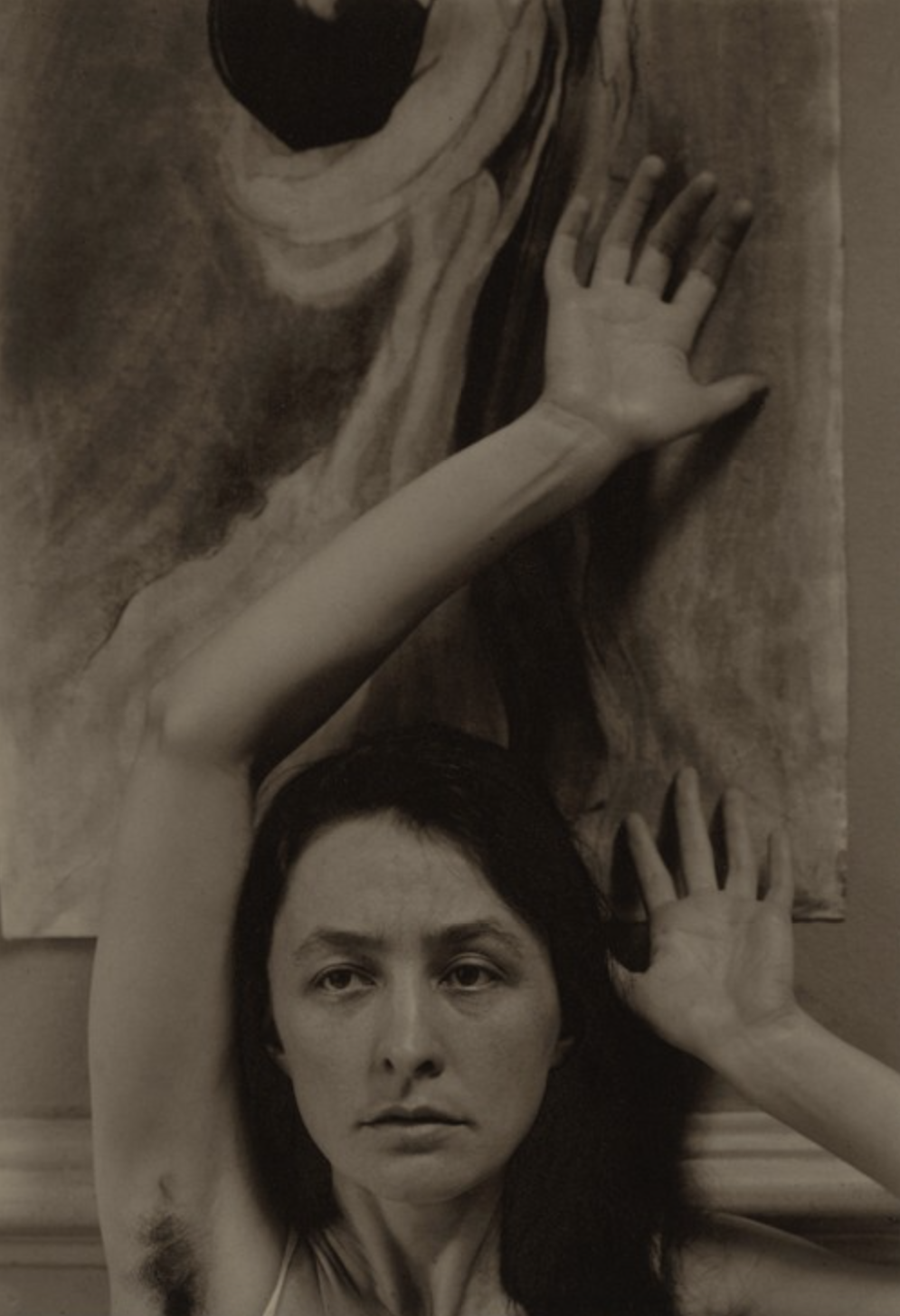

The photographer’s attitudes were also reflected in his approach to marketing O’Keeffe’s exhibitions; the catalogue for her 1923 show at Anderson Galleries included a Stieglitz-approved essay by fellow painter Mardsen Hartley. The piece positioned O’Keeffe as a “sexually obsessed,” distinctly feminine artist whose work was inexorably bound up with her body and self-perception.8 Hartley’s words colored much contemporary criticism regarding O’Keeffe’s work, as did Stieglitz’s decision to exhibit his photographs of the painter in 1921. These included nude images of O’Keeffe as well as photographs of her in front of her work—the curves of her face and body reflected in the organic, abstracted forms of her drawings and paintings (figure 3). These images, in the eyes of critics and the public, underscored Stieglitz’s argument that O’Keeffe’s work reflected her femininity.9

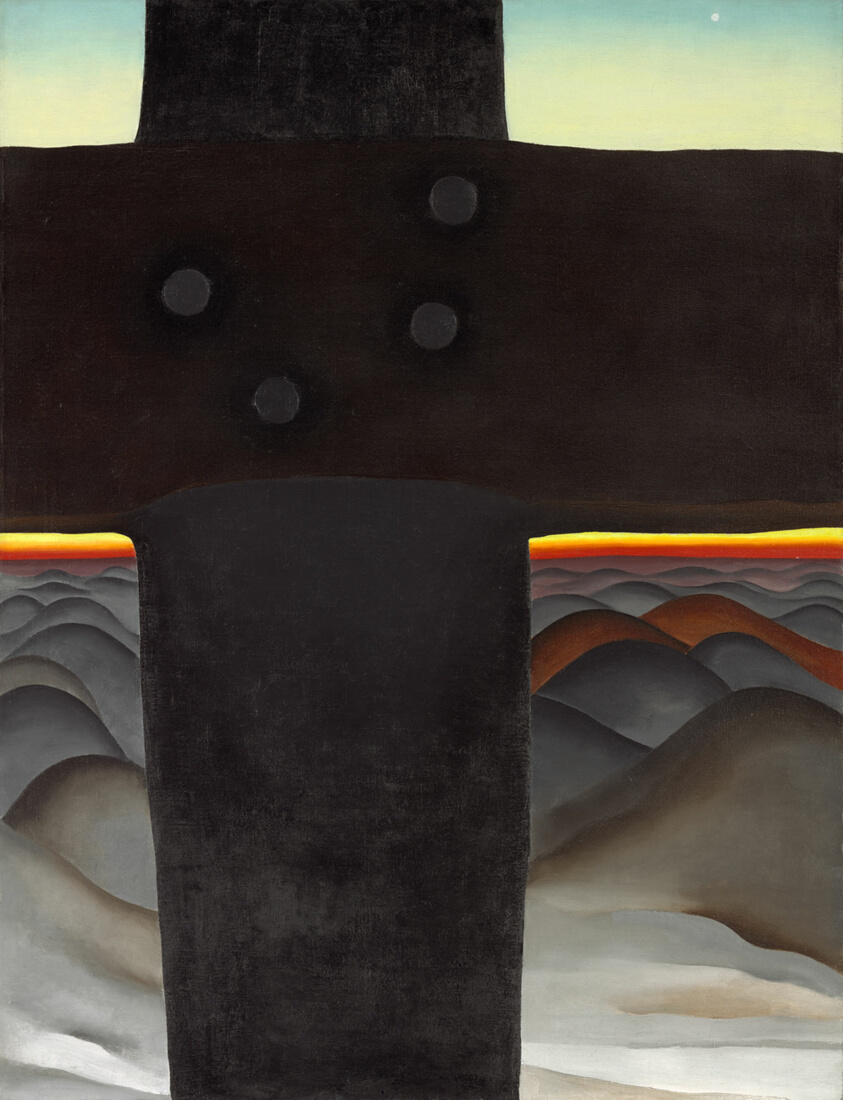

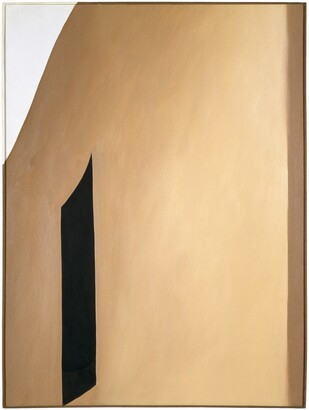

In addition to marketing O’Keeffe as a woman painter, Stieglitz did much to promote an image of her as an essentially American artist, and, more broadly, as a quintessential American. In the late 1910s, the photographer, who had long been a champion of modern art, began to narrow his focus to art made in the United States. O’Keeffe, as one of the artists he exhibited most often, necessarily became a part of this project. Tellingly, Stieglitz titled her 1923 exhibition Alfred Stieglitz Presents One Hundred Pictures: Oils, Water-colors, Pastels, Drawings, by Georgia O’Keeffe, American, placing particular emphasis on her nationality. In a group exhibition of 1925, Stieglitz further highlighted the Americanness of both O’Keeffe and the other artists featured at his galleries. His essay in the catalogue for the exhibition asked: “Are the pictures or their makers an integral part of the America of to-day?”.10 Though the other artists included in the exhibition, such as Arthur Dove, Mardsen Hartley, John Marin, and Paul Strand, were more often used as representatives of the American form of modernism Stieglitz hoped to promote, O’Keeffe’s art and personal circumstances were uniquely well-suited to this approach. She was born on a farm in a small town in Wisconsin, and during her youth and early adulthood lived in Virginia, South Carolina, and Texas. Her background in the American West and in the South was used to explain her aesthetic sensibilities, particularly in New York City where her works were first shown.

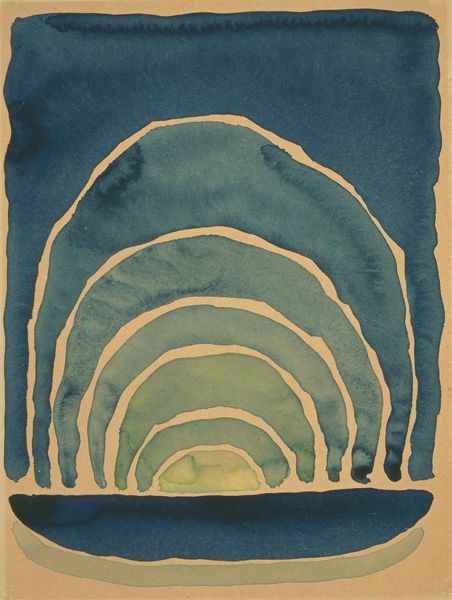

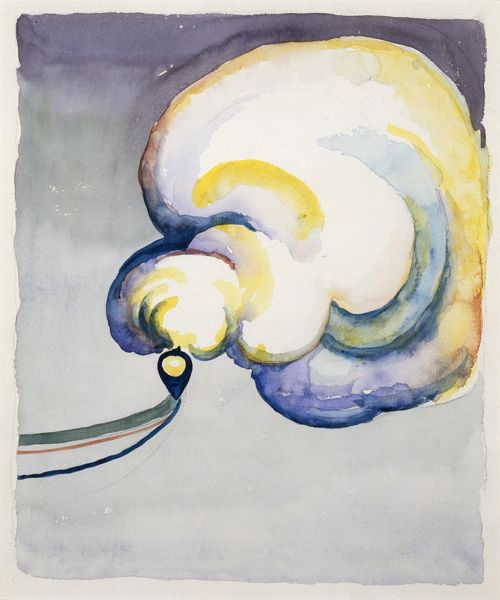

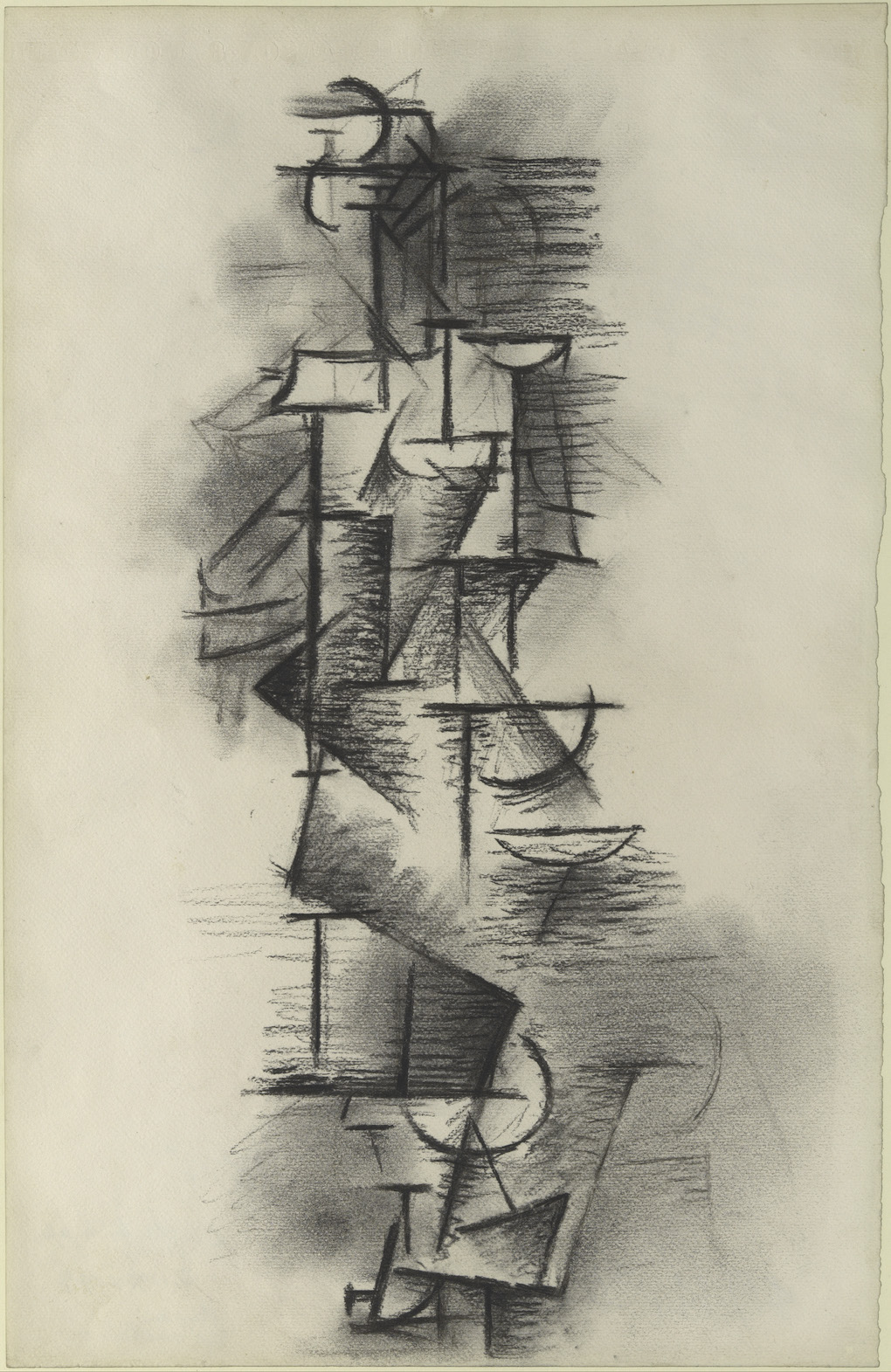

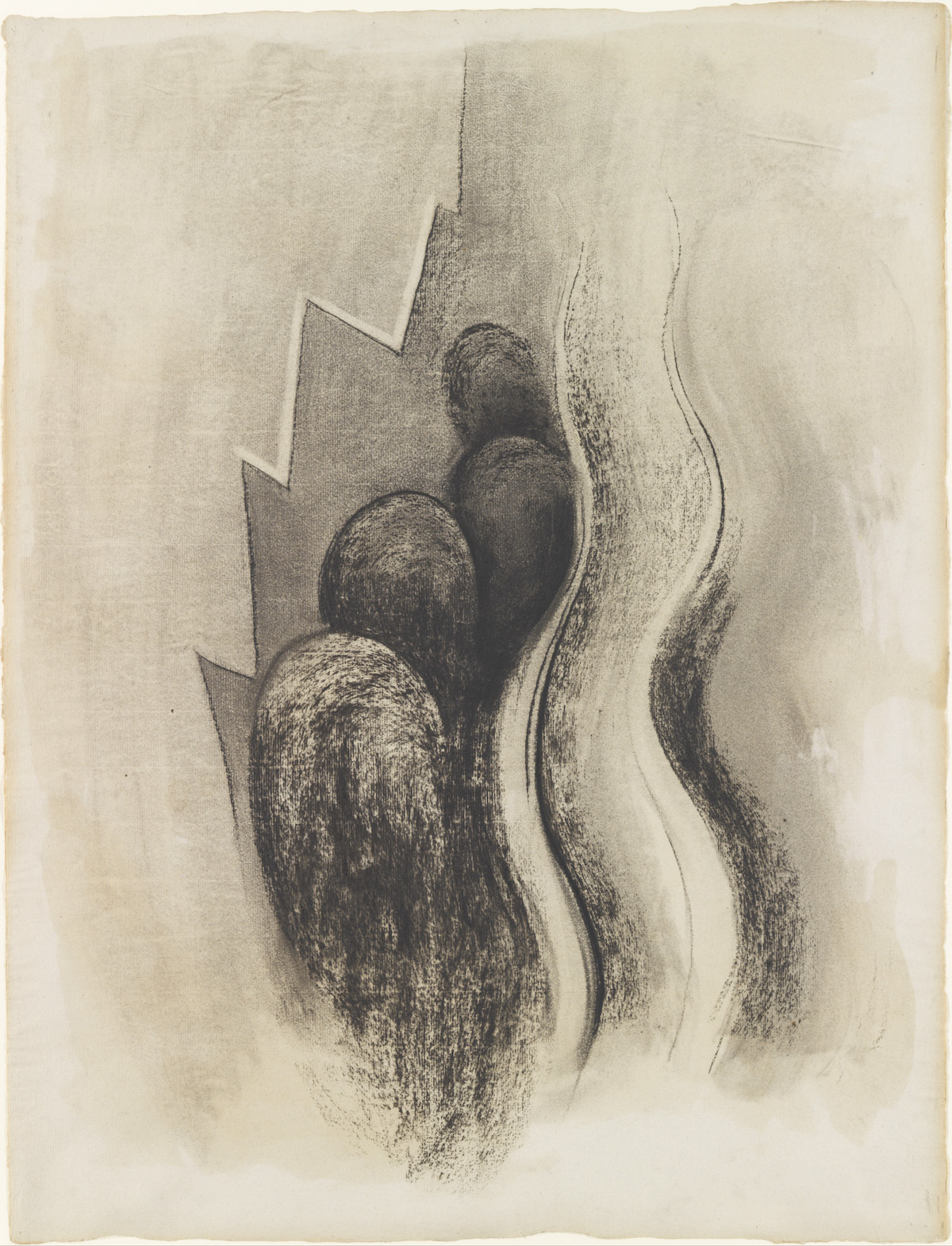

An additional factor that lent O’Keeffe the appearance of American originality was her lack of experience with and interest in European art. O’Keeffe first visited Europe well into her 60s, having expressed little prior desire for transatlantic travel. Further, unlike most of her male counterparts, she had not seen the Armory Show of 1913, one of the first major exhibitions of work by European modernists in the United States.11 While there is some evidence of European influence in her work, particularly in its modernist flavor (figures 4–5), its smoothness, color palette, and subject matter—much of it features elements of nature unique to the United States—stand in contrast to the work of influential Europeans such as Pablo Picasso or Georges Braque. Stieglitz selected O’Keeffe as exemplary of the evolution of an American style of modernism, referential of—yet distinct from—European trends. This positioning was successful. O’Brien’s profile of the artist argued that O’Keeffe was “an iconoclast to the old European traditions of art and artists,” that she was America’s “own exclusive product.”12

While O’Keeffe did not approve of some of Stieglitz’s tactics for promoting her work, his approach was undeniably effective. By presenting O’Keeffe’s work as distinctly Freudian in nature and representative of the attitudes of a sexually liberated woman, Stieglitz situated the artist within the zeitgeist of the 1910s and 1920s. He also attracted visitors to her exhibitions—500 people per day viewed her 1923 show at Anderson Galleries, and it won her fame in the New York art scene.13 Furthermore, O’Keeffe did little to counteract the eroticized and gendered interpretations of her work at the time, possibly because the tactic was so successful or due to the complication that disagreeing with Stieglitz publicly would precipitate. The other prong in Stieglitz’s marketing approach—promoting O’Keeffe as a thoroughly American painter—also helped to advance her new version of modernism. This view of the artist lasted for decades and was complemented by her later life and artistic choices made in New Mexico. Both elements of Stieglitz’s approach contributed to the formation of O’Keeffe’s cult of personality, which emerged with these first Stieglitz-sponsored exhibitions.

O’Keeffe’s cult of personality, while influenced by Stieglitz’s work, also emerged from her capacity for self-determination and individuality. O’Keeffe’s personal and artistic choices attracted attention from her earliest moments on the New York art scene, enhanced by her refusal to align herself with many of the popular political and cultural movements of the day. Though the artist was in close proximity to the bohemian cultural environment of Greenwich Village in the 1910s and 1920s, she stood out from other artists of her generation through her refusal to entirely embrace the aesthetic trappings of this lifestyle. She never bobbed her hair, and her clothing, though influenced by Village styles, was distinctly simpler than the items worn by her peers.14 Her lifestyle also reflected her distinct individualism and her ambivalence towards bohemian culture. While O’Keeffe practiced its “free love” approach by living with Stieglitz out of wedlock, her friend Frances O’Brien was quick to note that she had no interest in smoking, drinking, or other forms of “Bohemianism.”15 O’Keeffe also chose not to live in the Village, but instead had an apartment farther north, in Midtown—a sign of further alienation from elements of this society. These choices set O’Keeffe apart from other aspiring female artists of her social milieu. Yet, her early professional success produced a contingent of admirers from this very group. In his review of O’Keeffe’s 1923 exhibition, critic Henry McBride mockingly addressed O’Keeffe’s popularity with young, artistic women in New York, joking that O’Keeffe should “get herself to a nunnery” to avoid the female admirers she would gain from the successful exhibition.16

O’Keeffe’s attitude toward the feminist movement also reflected her sense of self-determination. While she identified with feminism early in her career, O’Keeffe wished to be viewed as an artist first and foremost, rather than as an avatar for the movement. Due to this, she had a somewhat ambivalent relationship to their cause. While her relationship with Stieglitz reflected her modern attitude toward marriage and monogamy, O’Keeffe never used the word “feminist” to describe herself.17 Later in life, she even rejected the movement outright as she did not recognize herself in the feminism of the 1970s.18 Once, when asked by artist Judy Chicago to participate in an anthology of women artists, she replied that one is either “a good painter or one is not, and that sex is not the basic [sic] of this difference.”19 In her emphasis on parity and freedom of choice, rather than on strict adherence to a code of values, O’Keeffe was ahead of her time—she pioneered a relationship to feminism similar to contemporary attitudes. Nevertheless, in the popular imagination, both her early association with feminism and her determination to become successful in an historically male-dominated sphere led to her identification as a feminist icon in later years.

Certainly the most important opportunity for O’Keeffe to express her individuality was through her art. While she aligned herself with the American modernists, her work was distinct from the paintings of Dove, Hartley, Marin, and others. Her simplified abstractions of nature—including large-scale representations of plant life (figure 6)—contrasted with the visually complex, impressionistic watercolors of John Marin (figure 7) due to their smooth surfaces and bright colors. Critics struggled to find the proper terminology for her art; some called her a “Futurist,” while others claimed she was a “Cubist.”20 The uncategorizable nature of her work allowed her to shake off such labels to conceive a new sort of modernism. Through her refusal to fully identify with bohemianism, feminism, or any other movement of her day, O’Keeffe pioneered new forms of them all.

O’Keeffe’s and Stieglitz’s efforts to promote her work plainly influenced critical and public perception of the painter’s life and work, but the pair could not altogether control O’Keeffe’s “image.” Due to her position as an artist who refused artistic and social categorization as well as her explosive popularity, early response to O’Keeffe’s exhibitions also constituted a response to O’Keeffe’s personhood. Profiles of the artist demonstrated the public’s fascination with her identity, particularly regarding her womanhood. As a fashionable and well-connected woman, she came to be seen as a symbol of cultural movements that she alternately rejected and embraced—early feminism, bohemianism, and American Modernism. Public fascination with O’Keeffe has carried through to this day, with the Brooklyn Museum exhibition Living Modern being perhaps the clearest manifestation of this phenomenon. This thoughtful examination of O’Keeffe’s deliberateness in all elements of her life fed the public’s fascination with the artist’s persona and argued that an artist’s work cannot necessarily be separated from their life.21

Whether a close reading of an artist’s personal identity clarifies or muddies our understanding of their work, the critical conflation of O’Keeffe’s own life and work enshrined her as (perhaps) the first modern American celebrity artist. Like her contemporary Frida Kahlo, however, this status as a national icon came at some cost. She gained fame, but not entirely on her own terms. Her images have been coopted to represent any number of identities as well as used to sell products. Nevertheless, during her lifetime O’Keeffe maintained a degree of personal independence, including in matters of personal style and identity that reflected her unwavering individuality—throughout the maelstrom of press she received into old age, she remained true to herself. In an era in which art and life have become integrated as never before, when self-creation and -curation have become mainstays of popular culture, perhaps this is, as much as anything, the great lesson gained from her early critics.

Notes

Note on titles of works: Institutional titles and dates for O’Keeffe’s works sometimes vary from first titles and dates established by Georgia O’Keeffe: Catalogue Raisonné (1999), whose entries explain changes. Here institutional titles and dates are listed first followed by those in the Catalogue Raisonné.

-

Frances O’Brien’s profile “Americans We Like: Georgia O’Keeffe” for the October 1927 edition of The Nation was one of a series of brief profiles of Americans for the magazine. O’Brien was a friend of both O’Keeffe and Stieglitz, and her portrayal of the artist reflects a deep knowledge of their ambitions for O’Keeffe’s public image. The profile acknowledges O’Keeffe’s status as an iconic, distinctly American painter, in line with Stieglitz’s wishes, without trading in the Freudian, sexualized interpretations of O’Keeffe’s works that the artist so resented. Frances O’Brien. “Americans We Like: Georgia O’Keeffe. The Fourth in a Series of Personality Portraits.” The Nation, October 12, 1927, 351. ↩︎

-

See Christopher Knight, “Beyond the O’Keeffe Mystique,” Los Angeles Times, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2000-mar-12-ca-7871-story.html. ↩︎

-

See Wanda M. Corn, Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern (New York: Prestel Publishing, 2017), 61. ↩︎

-

See Anita Pollitzer, A Woman on Paper: Georgia O’Keeffe (New York: Simon & Schuster Books, 1988), 48. This publication misdates the letter Pollitzer wrote O’Keeffe the night of December 31, 1915 to January 1, 1916, which is the postmark on the letter’s envelope rather than the day it was written. ↩︎

-

See Barbara Buhler Lynes’s essay, Georgia O’Keeffe’s “1946 Museum of Modern Art Exhibition: A Validation of Myth”, in this catalogue. ↩︎

-

See Linda Grasso, Equal Under the Sky: Georgia O’Keeffe and Twentieth Century Feminism (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2017), 55. Grasso examines O’Keeffe’s complex relationship to feminism as well as her outsized role as a contemporary feminist icon. ↩︎

-

Pollitzer, 164. ↩︎

-

See Barbara Buhler Lynes, O’Keeffe, Stieglitz, and the Critics, 1916-1929 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991), 25. This collection of critical materials analyzes public response to O’Keeffe’s early exhibitions, arguing that Stieglitz encouraged interpretations of the artist’s work that focused on her gender identity and an eroticized, Freudian interpretation of her work. ↩︎

-

See Roxana Robinson, Georgia O’Keeffe: A Life (Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England, 1999), 257. In this section of her book, Robinson explains the possible origins of eroticized interpretations of the painter’s work. ↩︎

-

Alfred Stieglitz, “Foreword,” Alfred Stieglitz Presents Seven Americans: 159 Paintings, Photographs, & Things, Recent & Never Before Publicly Shown, by Arthur G. Dove, Mardsen Hartley, John Marin, Charles Demuth, Paul Strand, Georgia O’Keeffe, Alfred Stieglitz (New York: Anderson Galleries, 1925), 2. The essay was one of several in the catalogue that positioned these artists as Americans working in a new style, having rejected the influences of European modernism. A piece by Arnold Rönnebeck, titled “Through the Eyes of a European Sculptor” (pp. 5–7), argued that the exhibition represented “nothing less than the discovery of America’s independent role in the History of Art.” Critical response to the exhibition was mixed and colored by what many saw as a pompous collection of essays in the exhibition catalogue. O’Keeffe’s work, however, was almost universally praised. ↩︎

-

See Pollitzer, XXIV. ↩︎

-

See O’Brien. ↩︎

-

See Robinson, 254 ↩︎

-

See Corn, 61. In this section, the curator offers an extensive analysis of O’Keeffe’s early style and propensity for standing out through her dress. ↩︎

-

See O’Brien. ↩︎

-

Henry McBride’s February 4, 1923, review of O’Keeffe’s show for the New York Herald poked fun at eroticized interpretations offered by other critics and emphasized her growing popularity with young women in New York. His tongue-in-cheek, hyperbolic description of the masses of O’Keeffe’s “sisters,” who were hounding her for artistic advice, underscores the emergence of O’Keeffe’s first cult of personality, a microcosm of educated, wealthy, young, female artists in the city. ↩︎

-

See Grasso, 11. ↩︎

-

See Barbara Buhler Lynes, “Georgia O’Keeffe and Feminism: A Problem of Position,” in The Expanding Discourse: Art History and Feminism, eds. Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard (New York: HarperCollins, 1992), 436–49. ↩︎

-

See Haley Mlotek, “Georgia O’Keeffe’s Powerful Personal Style,” The New Yorker, April 6, 2017, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/georgia-okeeffes-powerful-personal-style. ↩︎

-

For the quotes, see “Another ‘Futurist at the Photo-Secession’,” American Art News 15, no. 26 (April 7, 1917); and McBride. ↩︎

-

See Corn, 283. ↩︎