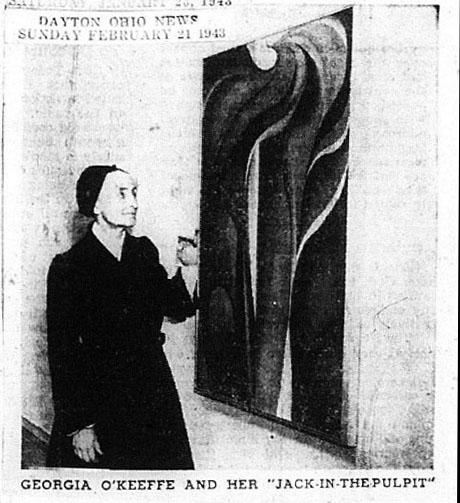

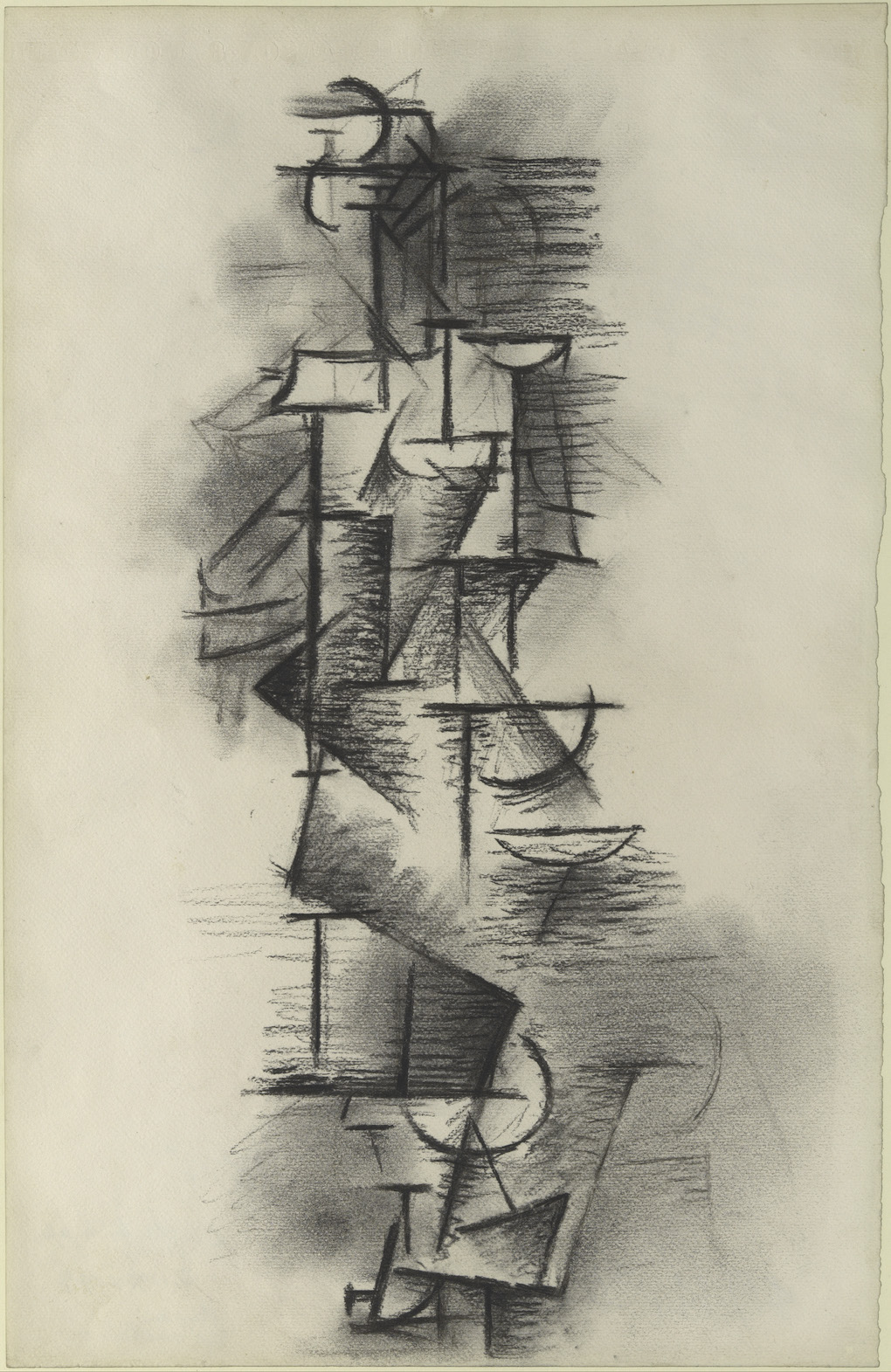

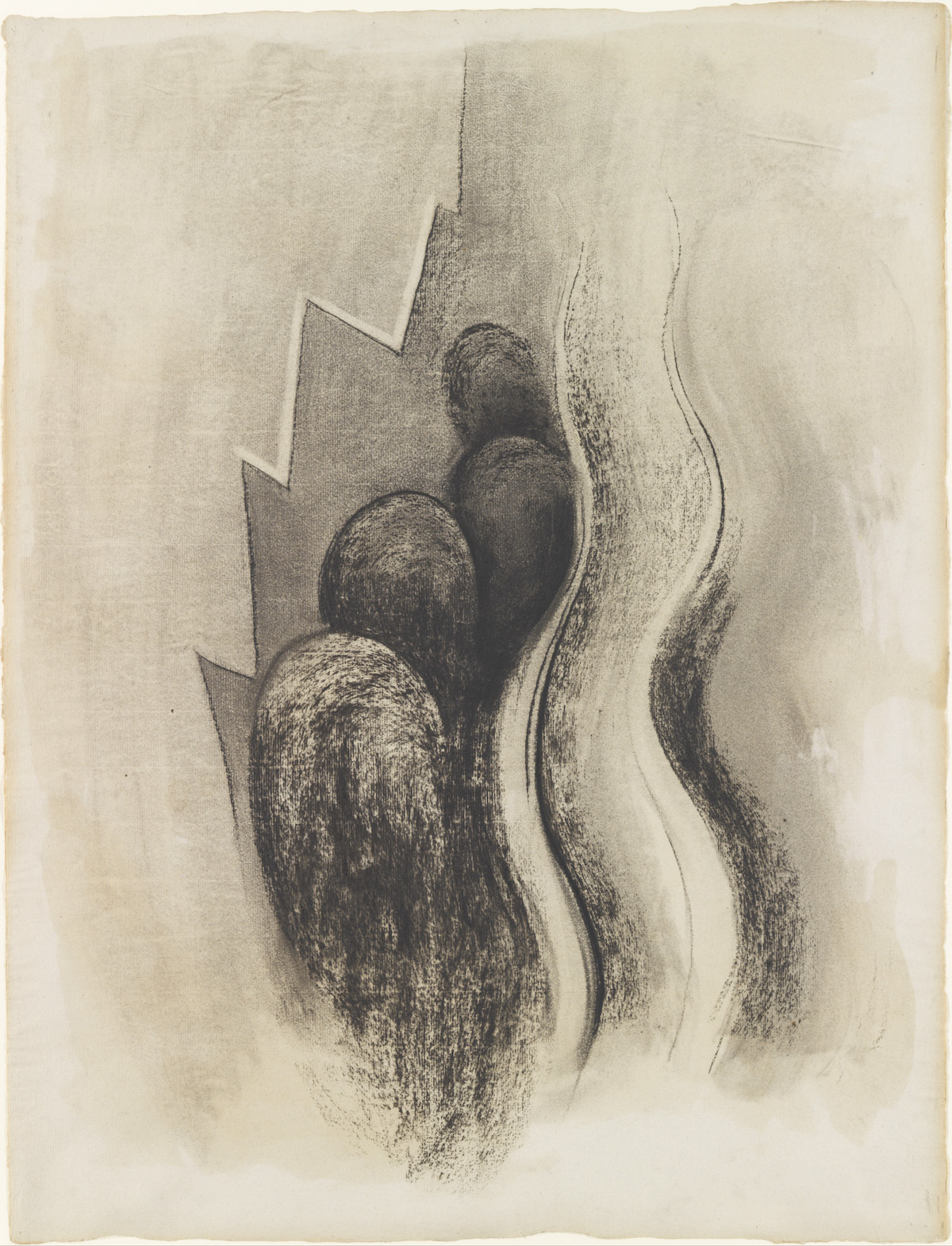

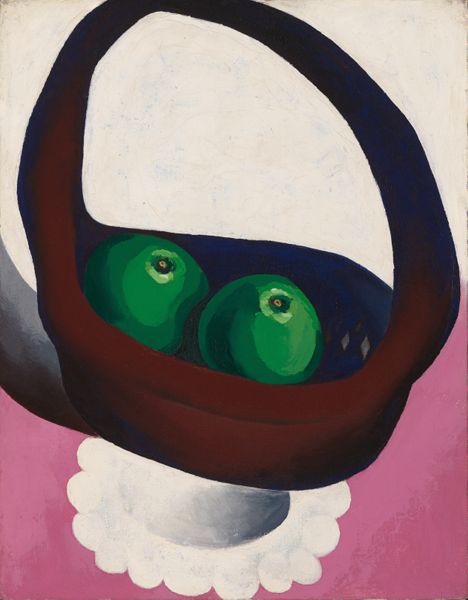

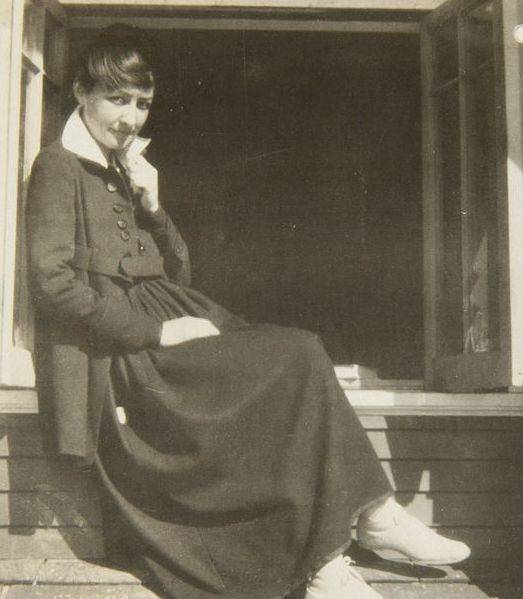

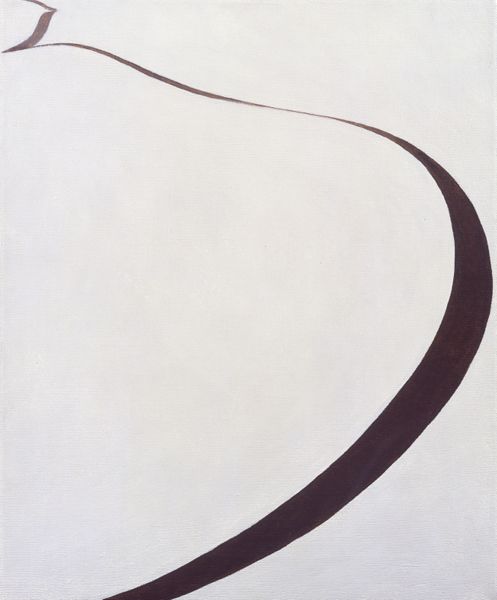

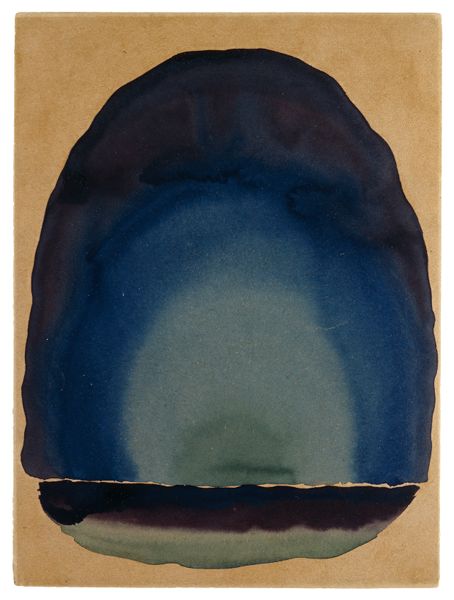

Aspects of the significance of the well-received Georgia O’Keeffe retrospective exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1946 have long been recognized in the O’Keeffe literature (figure 1).1 It was the artist’s first retrospective in the epicenter of the American art community and the museum’s second exhibition devoted to the art of a woman.2 What follows identifies another equally important component of the exhibition’s significance. The press release and its subtitle, “Finally, a Woman on Paper,” codified as fact and effectively set into motion arguably the most popular and pervasive myth in the O’Keeffe literature.

That is, the internationally known photographer, gallerist, and leading advocate of modern art in America, Alfred Stieglitz, supposedly exclaimed, “Finally, a Woman on Paper,” upon seeing O’Keeffe’s work for the first time on December 31, 1915. Indeed, from 1946 on, the phrase has been repeated nearly annually in reviews of O’Keeffe’s exhibitions, and in articles, books, and biographies about her. Yet, as will become clear, Stieglitz did not say “Finally, a Woman on Paper” that day despite the 1946 exhibition press release assertion that he did.

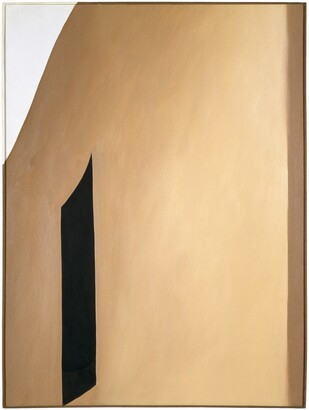

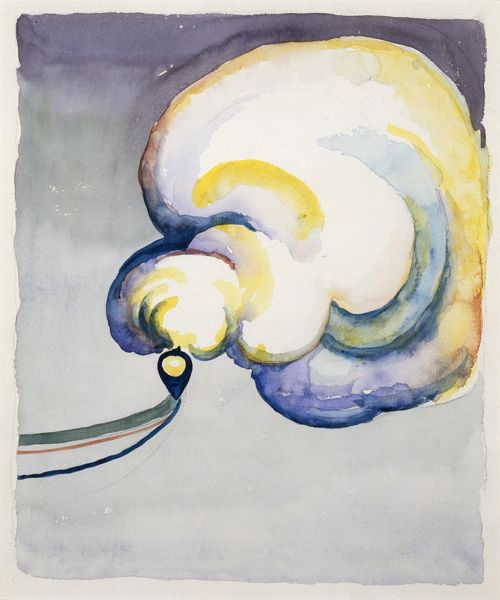

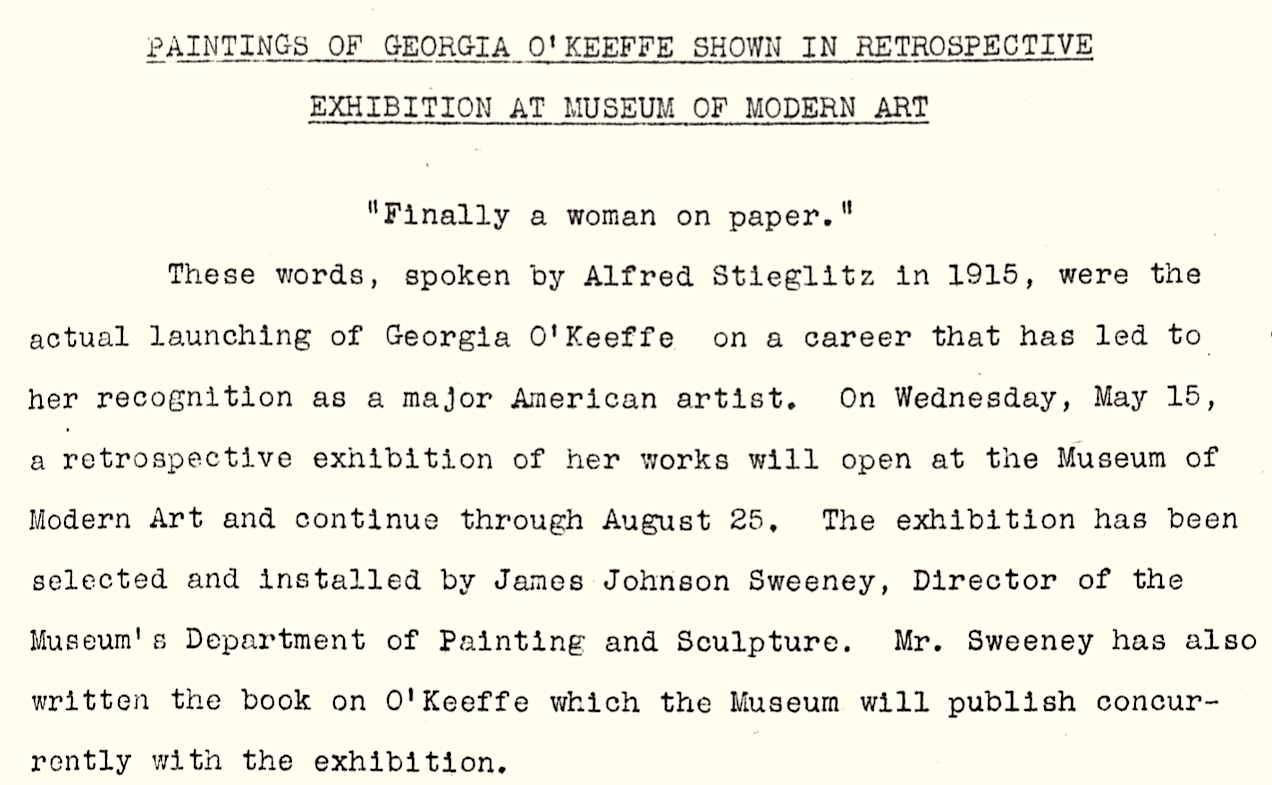

Exhibition curator James Johnson Sweeney was instrumental in preparing the 12-page press release (figure 2; pdf)—nine pages longer than those typical from the museum then. It included the exhibition checklist, lists of earlier O’Keeffe exhibitions and her paintings in public collections, her curriculum vitae, and information on her background and education. It also explained that her work had been influenced by artist and teacher Arthur Wesley Dow, and included O’Keeffe’s descriptions of important moments in the development of her art. There were also excerpts from the essay Sweeney was preparing for the exhibition catalogue, which was never published.3

The press release also featured a 1916 O’Keeffe letter to Stieglitz, who became her dealer that year and her husband in 1924. Its third page drew attention to this letter and to how Sweeney had obtained it: “In the catalog Mr. Sweeney quotes from a considerable group of unpublished early correspondence—generously put at his disposal by Miss O’Keeffe—between the artist and her discoverer, Alfred Stieglitz.” The “unpublished early correspondence,” however, also included letters O’Keeffe had written in June, August, and October 1915 and January 1916 to her New York friend and former classmate there, Anita Pollitzer.4

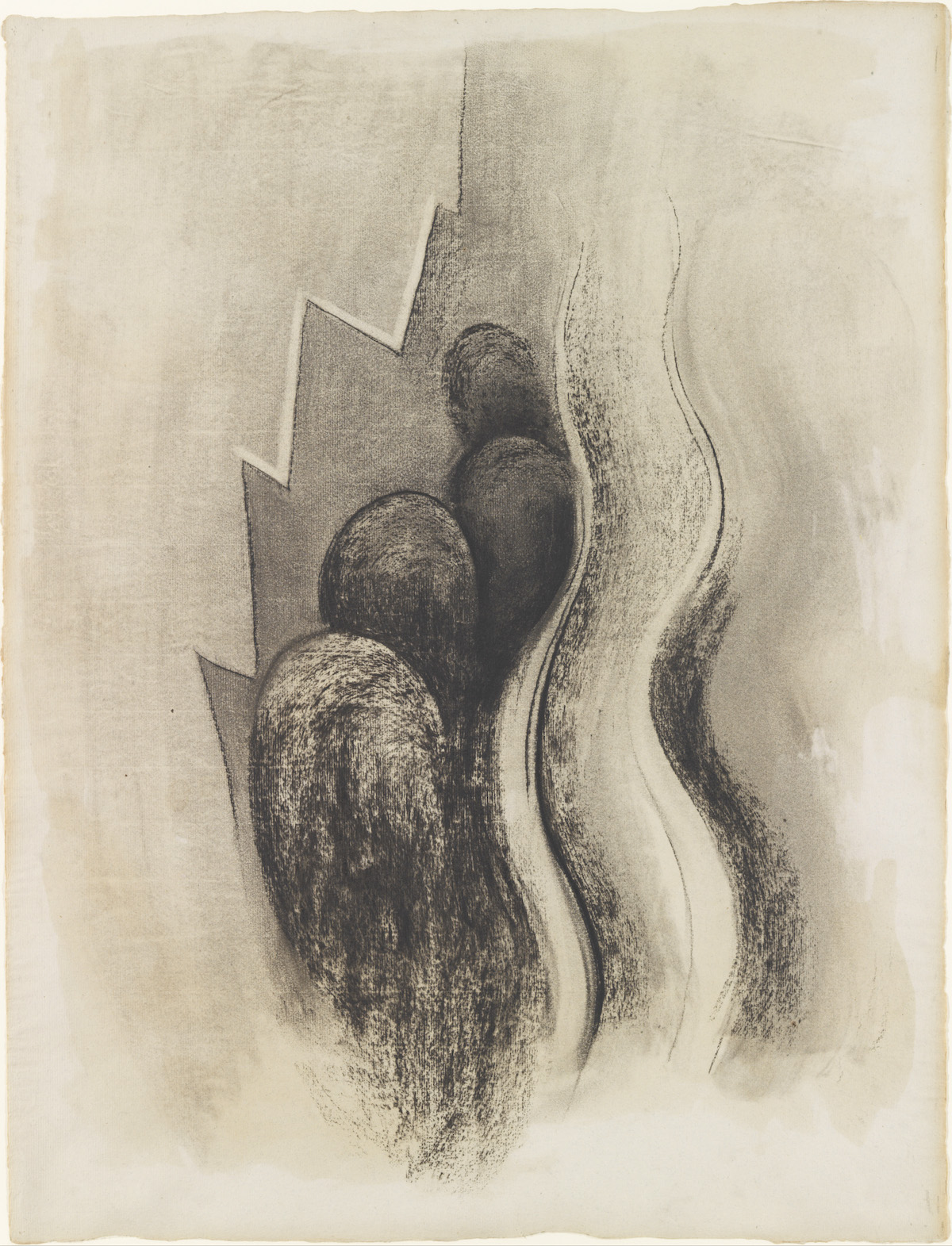

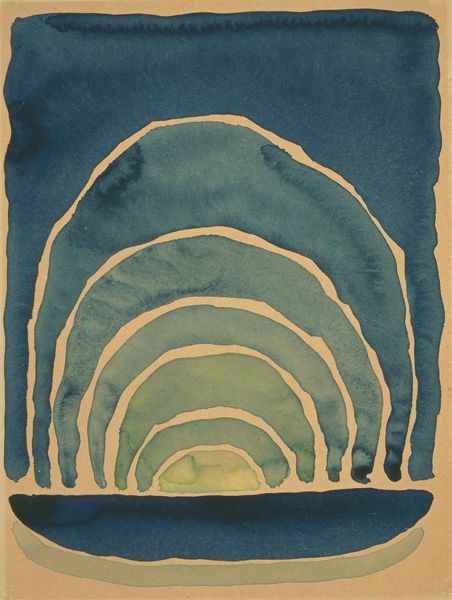

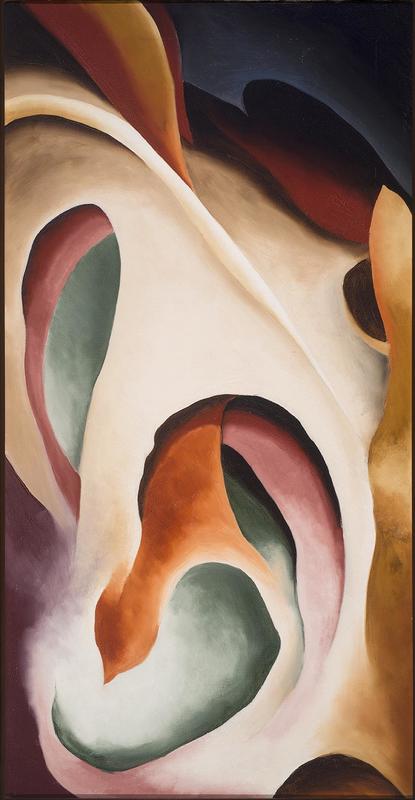

O’Keeffe was then teaching in South Carolina and had mailed her friend a series of recently completed drawings. Despite her directive to show them to no one, Pollitzer took them to Stieglitz at his famous avant-garde gallery, 291, on December 31, 1915. When he saw them, he supposedly proclaimed, “Finally a Woman on Paper.”

To be sure, the exhibition subtitle recalls Stieglitz’s description of O’Keeffe’s innovative abstractions when he first exhibited them in 1916. He wrote: “‘291’ had never before seen woman express herself so frankly on paper.”5 And the phrase is also reminiscent of how Stieglitz described O’Keeffe’s work in a late 1917 or early 1918 letter to his friend, photographer Anne Brigman, sent after the one-person O’Keeffe exhibition Stieglitz organized in 1917. He stated: “The room [291] was never more glorious than during its last exhibition—the work of Miss O’Keeffe—A woman on paper—Fearless. Pure Self-Expression.”6 And Stieglitz used similar words when writing O’Keeffe in 1918, when she was teaching in Texas: “Of course, I am wondering what you have been painting—what it looks like—what you have been full of—The Great Child pouring out some more of her Woman self on paper—purely—truly—unspoiled.”7 Yet none of Stieglitz’s words conveys the drama and promotional impact of “Finally, a Woman on Paper.”

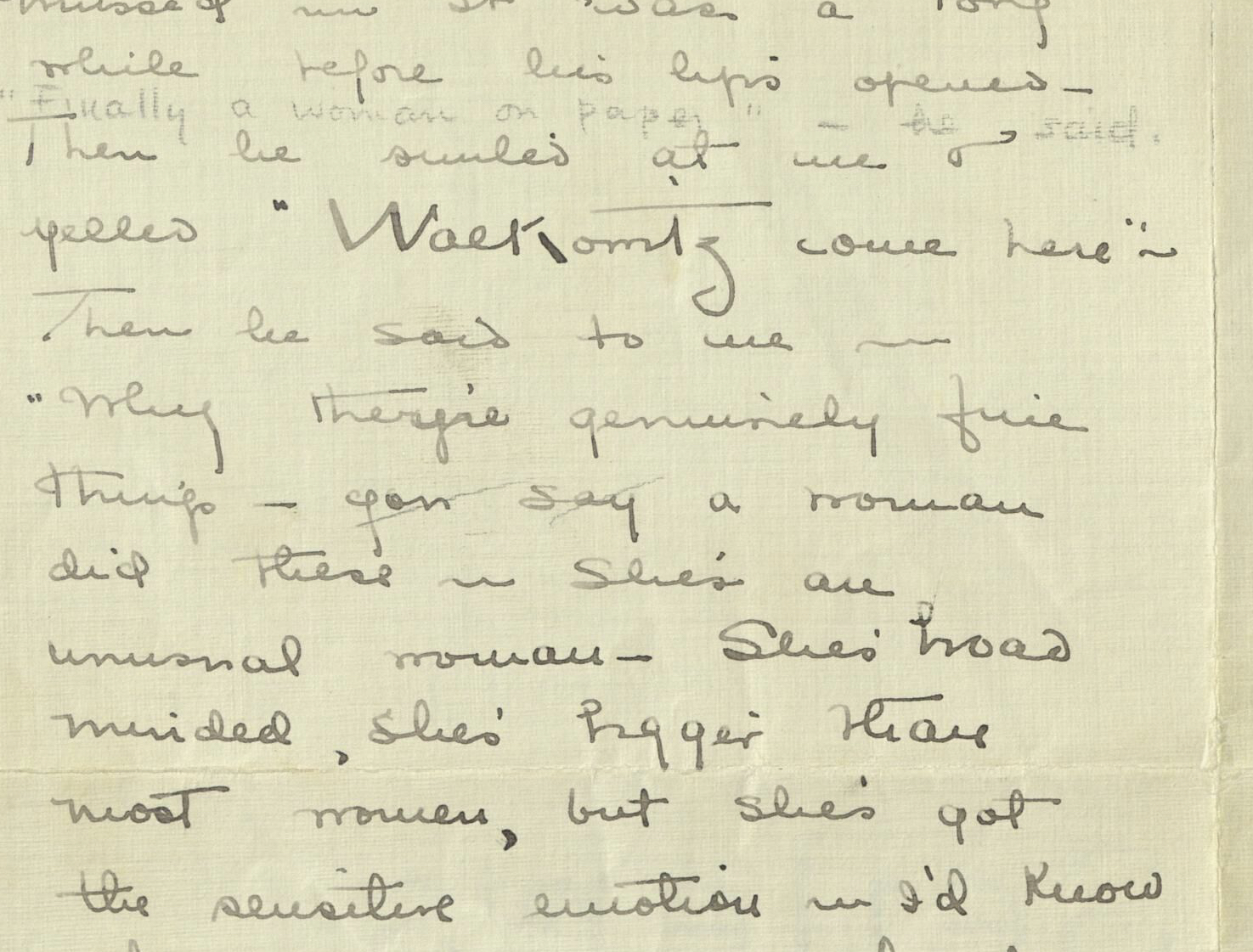

Had Stieglitz uttered the phrase in 1915, would Pollitzer not have remembered it when she wrote to O’Keeffe that evening, after she had taken O’Keeffe’s work to Stieglitz? Yet, her ink-written letter, penned in cursive, did not include it. Rather, it only stated: “Why they’re genuinely fine things—you say a woman did these—She’s an unusual woman—She’s broad minded, she’s bigger than most women, but she’s got the sensitive emotion—I’d know that she was a woman—Look at that line . . . they’re the purest, finest, sincerest things that have entered 291 in a long while . . . I wouldn’t mind showing them in one of these rooms one bit.”8

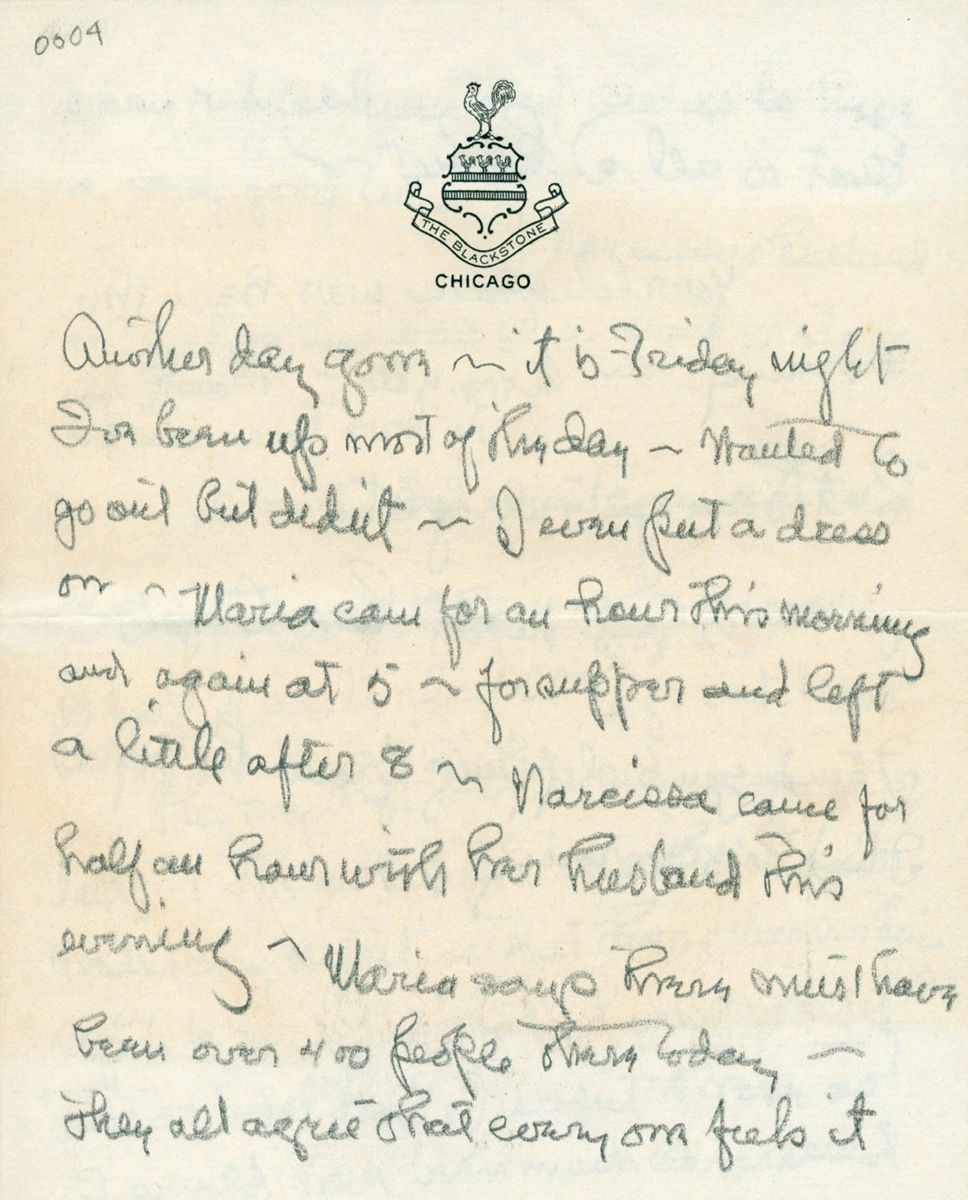

Moreover, would O’Keeffe not have repeated “Finally, a Woman on Paper” when writing her close friend Arthur Macmahon on January 6, 1916, when quoting from Pollitzer’s letter?9 Yet she wrote: “Stieglitz liked them [her drawings]. Said they were the purest finest sincerest things that had entered 291 in a long time—that he might want to show them later.”10 The absence of the phrase in O’Keeffe’s letter suggests it was not in Pollitzer’s. Yet, it is there now, mostly printed in pencil, in Pollitzer’s hand, and inserted between the cursive lines of Pollitzer’s ink-written letter (figure 3). It thus differs in medium, style, and tone from the more reasoned Stieglitz reaction Pollitzer recorded in ink. How, when, and why then did Pollitzer insert it into a letter that had been in O’Keeffe’s possession since receiving it in 1916?

Its different mediums were first noted in the literature in 1983 and the penciled phrase was then seen as something Pollitzer perhaps added as an afterthought before mailing the letter on January 1, 1916.11 Yet, this difference was soon obscured by the 1990 publication of the O’Keeffe/Pollitzer correspondence.12 It misdated Pollitzer’s December 31, 1915, letter as January 1, 1916, did not mention that the phrase was inserted between the lines of the letter, and made no distinction between its pencil and pen components. Those consulting the book rather than the original letter would not know that the phrase “Finally, a Woman on Paper” was inserted in pencil and might not be original to it. Considering O’Keeffe did not include the phrase in her letter to Macmahon as well as its history in the O’Keeffe literature, as will be reviewed here, it is more probable, as will become clear, that Pollitzer inserted the phrase in 1946 or shortly thereafter, when the phrase and its origin story were validated as fact in the 1946 O’Keeffe exhibition press release.

Although supposedly uttered in 1915, “Finally, a Woman on Paper” did not appear in the literature until 13 years later, which seems odd, given that a great deal had been written about O’Keeffe since 1916 and that the phrase was later considered “eminently quotable.”13 It was in reviewing O’Keeffe’s 1928 exhibition that Stieglitz’s friend Louis Kalonyne first recorded the phrase and its origin story: “‘Finally, a Woman on Paper!’—or words to that general effect—Stieglitz is reported to have said quite moved, to the New York girl friend of O'Keeffe's who had brought the drawings to him.”14 Yet, it did not then take hold in the O’Keeffe literature.

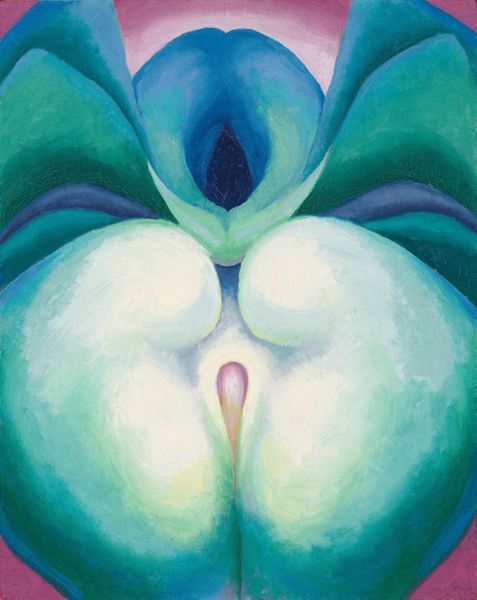

Both the phrase and its origin story surfaced again 13 years later, in a 1941, anonymously written entry on O’Keeffe in Current Biography.15 “Without her permission, the friend showed the drawings to Alfred Stieglitz, who is said to have ejaculated: ‘Finally, a Woman on Paper.’” Ejaculated rarely describes something said. Rather, it refers to the pleasure of male sexual climax. Its use here suggests that Stieglitz wrote or provided input for the entry as he greatly enjoyed provoking controversy. Moreover, the word alludes to how O’Keeffe and her art aroused and satisfied him, as well as to how he had perceived and promoted her art since 1916: as a manifestation of female sexuality.16

Two years passed before the phrase and its origin story were next cited. O’Keeffe’s and Stieglitz’s friend, curator Daniel Catton Rich, referred to both in his essay for the catalogue of O’Keeffe’s first retrospective exhibition that he organized at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1943. Rich pointed out: “To Anita Pollitzer in New York [O’Keeffe] sent in 1916 [sic] a roll of sketches with the express condition that they were not to be shown to anyone. . . . Disobeying O’Keeffe’s request she promptly tucked the roll under her arm and took them to one of the few men in America capable of appreciating them—Alfred Stieglitz. . . . He was instantly impressed by O’Keeffe’s drawings. ‘Finally, a Woman on Paper,’ he remarked.”17 One wonders if Rich cited the phrase and its origin story at Stieglitz’s suggestion as it had not yet gained much traction in the O’Keeffe literature, even after the 1941 provocative entry in Current Biography.

That Rich was unaware of the sexist implications of the phrase and its origin story are clear from his catalogue essay. It was the first in the literature to disassociate O’Keeffe’s art from the sexualized interpretations that had dominated its reception since 1916.18 Rich stated:

In the first review of the exhibit in Stieglitz’s own magazine, Camera Work, there occurs the suggestion that these drawings may be of psychoanalytic interest. Exciting as this observation was to a period fascinated by Freud, it has been, in the long run, harmful to O’Keeffe’s case as an artist. It set off a whole train of mystic and sexual explanations of her art which have sometimes stood in the way of understanding.19

“Finally, a Woman on Paper” was quoted once in reviews of the 1943 Chicago exhibition as “At Last, a Woman on Paper,” and again in 1945 in both forms.20 Janet Hollis reviewed O’Keeffe’s exhibition at Stieglitz’s gallery that year, stating “At Last, a Woman on Paper”; and “Finally, a Woman on Paper” was used in the title and cited in the text of an article on O’Keeffe in U.S.A. An American Review.21 But neither the phrase nor its origin story caught on in the O’Keeffe literature until 1946, when both were authenticated as fact in the O’Keeffe exhibition press release and subsequently repeated regularly in the literature. As seemingly unaware of the phrase’s sexist implications as Rich, Sweeney wrote: “These words [“Finally, a Woman on Paper”], spoken by Alfred Stieglitz in 1915 were the actual launching of Georgia O’Keeffe.”22

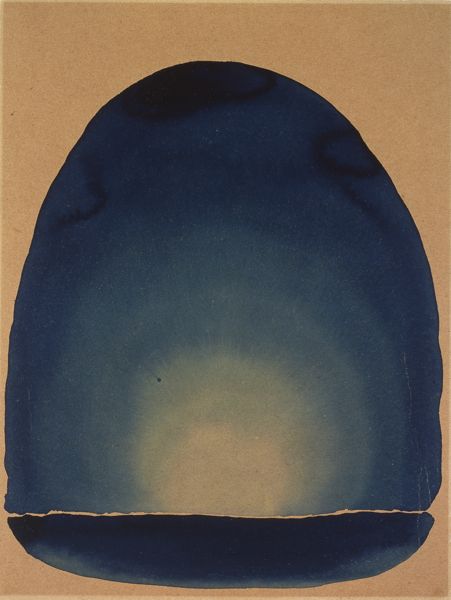

Curiously, given her later refusal to condone associating her art with her gender, O’Keeffe voiced no known objection to the phrase or its origin story.23 She most probably held the same opinion then that she had expressed in an interview with Michael Gold in 1930, stating: "I am trying with all my skill to do a painting that is all of woman, as well as all of me."24 She had first articulated her feelings about this issue when writing Pollitzer on January 4, 1916, about her 1915 charcoal abstractions: “The thing [her work] seems to express in a way what I want it to but—it also seems rather effeminate—it is essentially a womans [sic] feeling—satisfies me in a way.”25 And, by 1946, like the men, O’Keeffe may have believed Stieglitz had uttered “Finally, a Woman on Paper” when first seeing her work.

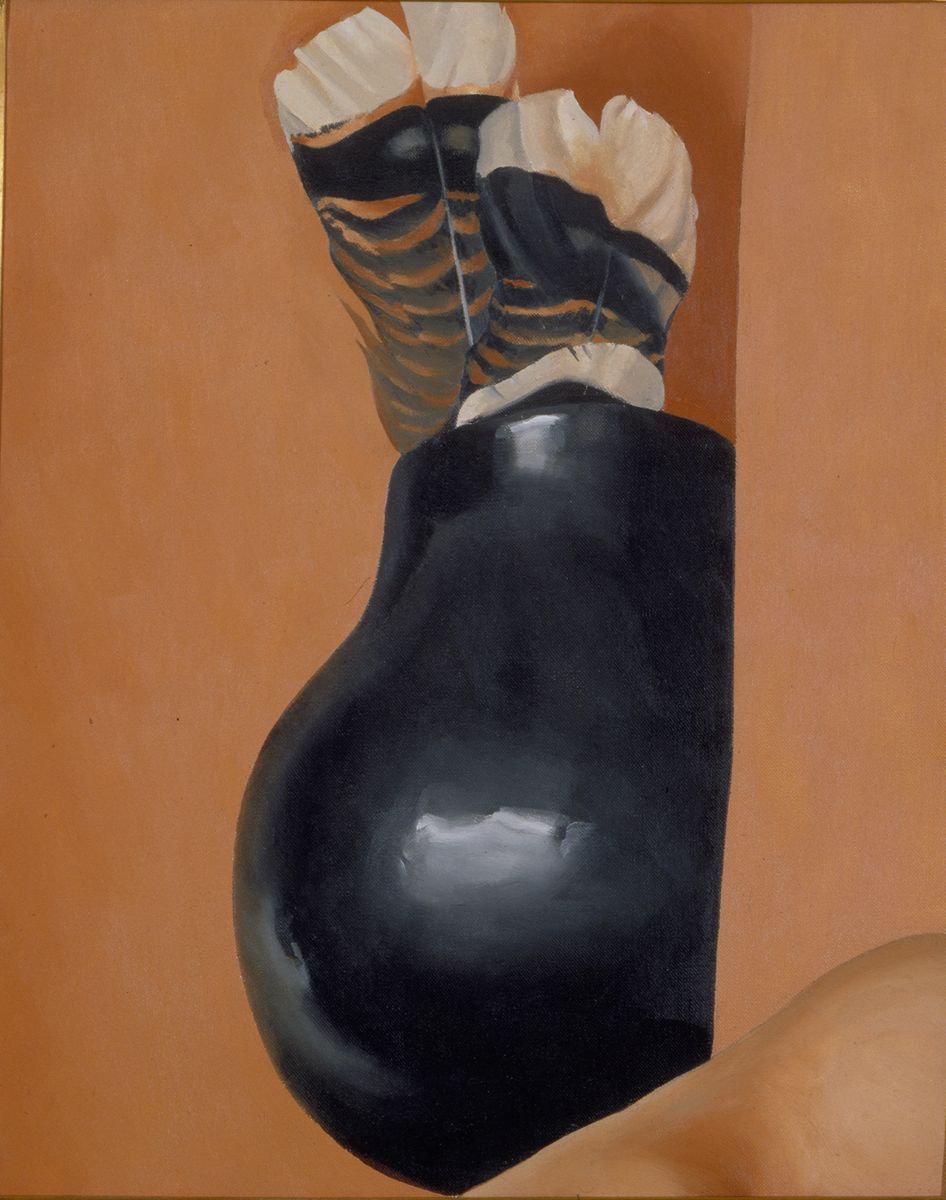

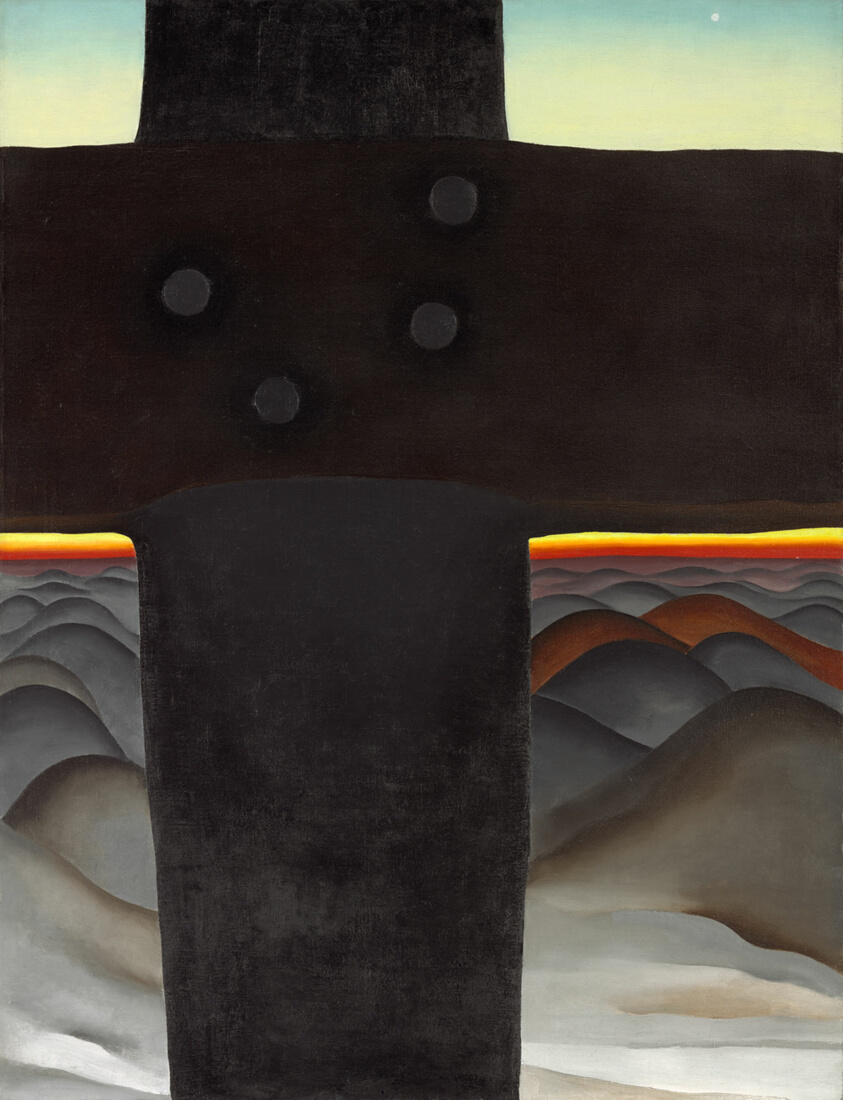

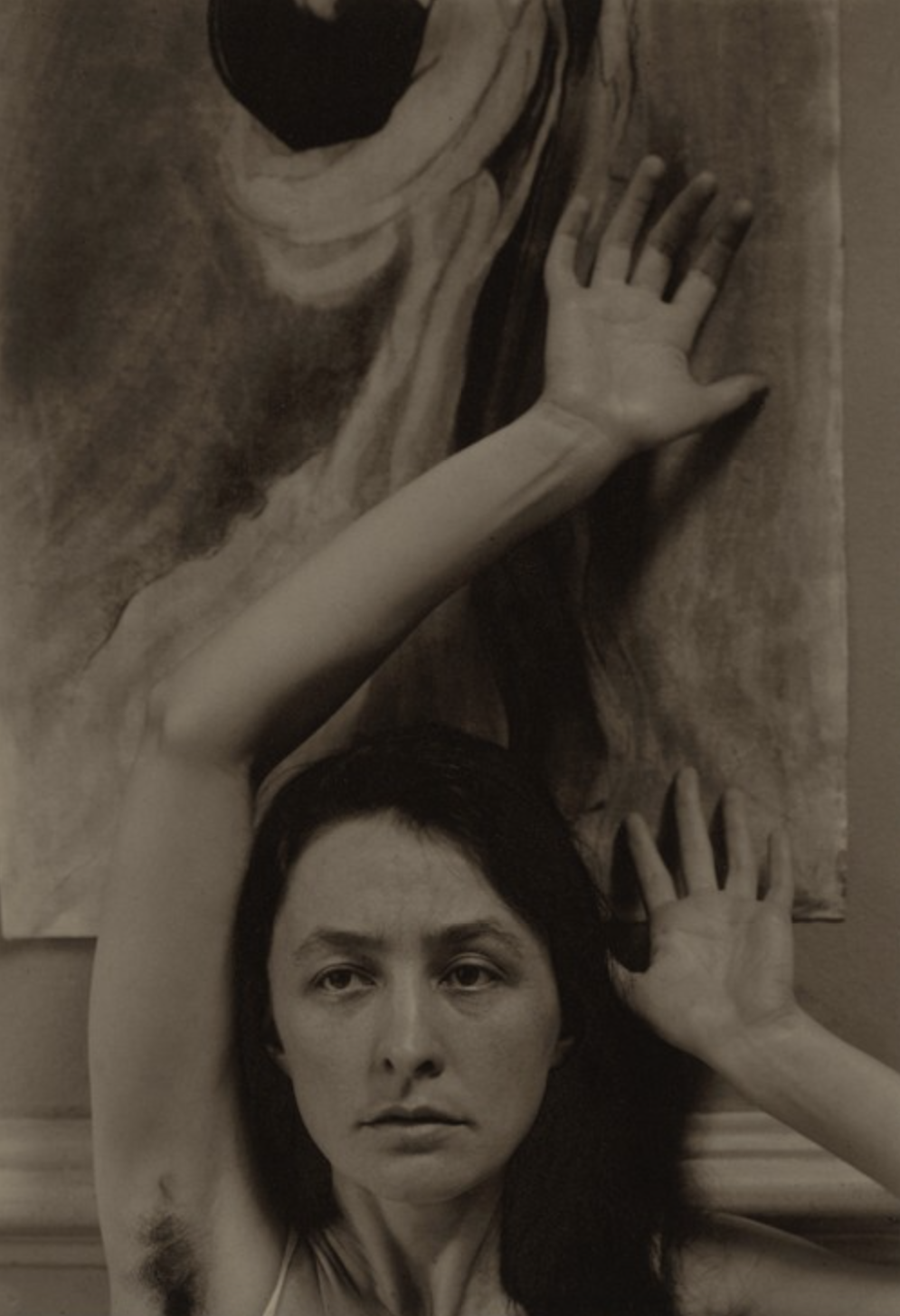

And she may have realized that the phrase, while referring to her own accomplishment, also indirectly called Stieglitz’s to mind. Long before the 1946 exhibition, Stieglitz had realized arguably his most outstanding achievement, an extensive photographic portrait of O’Keeffe. He completed it between 1917 and 1937, when he retired from photography, and it was clearly his own “Woman on Paper.” Stieglitz’s early photographs of O’Keeffe often presented his subject in the nude, partially dressed, and occasionally posed in front of her abstract works, gesturing toward them with her hands. He had exhibited 45 of them in 1921, when he was still married to his first wife and living with the unmarried O’Keeffe—the exhibition created a sensation.

Clearly, Sweeney had Stieglitz’s “Woman on Paper” in mind. In excerpts from his catalogue essay, which the press release included, he subtly referred to the 1921 exhibition. He stated: “An expression of intense emotion, stark but always constrained, is the essence of O’Keeffe’s art. And the way she came to this was by the severest critical self-stripping.” The anonymous critic for Time riffed on Sweeney’s words, making “Austere Stripper” the title of the review. Art critic Henry McBride’s review referred to the event directly:

There came to notice almost at once something about some photographs showing every conceivable aspect of O'Keeffe that was a new effort in photography and something new in the way of introducing a budding artist. It made a stir. Mona Lisa got but one portrait of herself worth talking about. O'Keeffe got a hundred. It put her at once on the map. Everybody knew the name. She became what is known as a newspaper personality.26

That Sweeney was thinking about Stieglitz’s “Woman on Paper” is also evident from his suggestion that Stieglitz exhibit examples of it in a gallery adjacent to those of O’Keeffe’s exhibition.27 Stieglitz rejected the idea because it would not represent the breadth of his achievement. Yet this was perhaps an excuse, knowing full well how the 1921 exhibition had upset and outraged O’Keeffe. It provided visual equivalents for how Stieglitz was promoting O’Keeffe’s art and prompted critics to associate her art with her body and her sexuality. Indeed, and perhaps at O’Keeffe’s insistence, he only occasionally exhibited one or several of these photographs during his lifetime after 1921.28

Whatever the case, O’Keeffe was in support of most of Sweeney’s efforts. She had allowed him to publish one of her letters to Stieglitz in the press release and had asked Pollitzer to provide him with letters she had sent her friend. The women had remained friends and were both living in New York in 1946, until June, when O’Keeffe left to spend the summer in New Mexico. Pollitzer had made her O’Keeffe letters available to Sweeney, and because she was preparing a review of O’Keeffe’s 1946 exhibition must have asked in turn for access to her letters to O’Keeffe.29 In reviewing her December 31, 1915, letter, she must have realized “Finally, a Woman on Paper” was not there.

Pollitzer was unaware of the degree to which the phrase’s promotional ring differed from the more cautious Stieglitz response she had described in the original letter, its history and origin story in the literature, or that inserting it then in pencil would later call its originality into question. Yet, she knew that “Finally, a Woman on Paper” had become the mantra of the 1946 press release and may have thought she had not remembered exactly how Stieglitz had responded when she showed him O’Keeffe’s work some 30 years earlier. She thus amended her letter to correspond with the premise and subtitle of the 1946 press release. She either added it then or shortly thereafter, when she was preparing the article “That’s Georgia,” published in Saturday Review (1950). In it, she cited the phrase and its origin story, as was the case in her posthumously published book about O’Keeffe, A Woman on Paper.30

Stieglitz died on July 13 at 86 during the run of O’Keeffe’s exhibition, but not before enjoying the adulation heaped on him in Sweeney’s press release and the critical response it and the exhibition generated. While these materials celebrated O’Keeffe and her astonishing achievements, they also drew inordinate attention to Stieglitz. For example, the press release stated: “For more than a decade [Stieglitz has] been introducing to the American public the most modern painting and sculpture from abroad as well as the most advanced American art.” Additionally, it highlighted the role he had played in discovering, promoting, and championing O’Keeffe’s art, the annual exhibitions he had organized of it, as well as the avant-garde publications he had founded, 291 and Camera Work, calling them “the most radical publications of their kind in America.”

Indeed, adulation for Stieglitz so dominated the press release that the critic for Art News called attention to it:

Georgia O’Keeffe’s full-length retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art is a very useful affair. If you walk through it before you read the catalogue [press release] you will be able to form your own picture of what she represents in American art without interruptions on the part of Mr. Stieglitz. The ‘291’ publicity technique need not bewilder you in all its wonderful simplicity until you feel ready to take it.31

Whether Stieglitz suggested the exhibition subtitle to Sweeney or played a part in developing the press release will never be known, but the 1946 exhibition served both artists well. Its press release highlighted the significance of O’Keeffe’s breakthrough charcoal drawings while alluding to Stieglitz’s “Woman on Paper,” and validated as truth the myth of his prescience in immediately realizing her potential as early as 1915.32 It and the press release inexorably linked the two, hitching the aging Stieglitz to the star the much younger O’Keeffe had become, providing Stieglitz a permanent place in the O’Keeffe literature. Indeed, it is not possible to discuss O’Keeffe’s life, art, or career without mentioning Stieglitz.

While this may continue to be the case, it is now clear for the first time that Stieglitz was not as perceptive in 1915 as the myth of his then saying “Finally, a Woman on Paper” implied. He did not come up with the phrase and its origin story until over a decade later, when he developed it as a promotional tool. Stieglitz had no way of knowing that the phrase was not part of the Pollitzer letter that described his reaction to first seeing O’Keeffe’s work but was instead added decades later. Nor could he have imagined that the letter would ultimately reveal as myth the 1946 release and its subtitle’s assertion that Stieglitz had uttered “Finally, a Woman on Paper” as early as 1915.

Notes

-

For an assessment of the criticism the exhibition received in 1946, see Barbara Buhler Lynes, “Georgia O’Keeffe and Henry Moore: Icons, Innovators, Voices of Authority,” Moore and O’Keeffe: Bones and Stones to Oil and Bronze, exh. cat. (San Diego: San Diego Museum of Art, 2023), forthcoming. ↩︎

-

The first was the 1942 Josephine Joy exhibition. ↩︎

-

The exhibition press release and installation photographs are available on the Museum of Modern Art website: https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2851. Letters exchanged between O’Keeffe and Sweeney after 1946 indicate that he continued to work on the catalogue essay, but never completed it. ↩︎

-

The press release misdates the January letter to November 4, 1915. ↩︎

-

See Alfred Stieglitz, "Georgia O'Keeffe—C. Duncan—Réné [sic] Lafferty," Camera Work, no. 48 (October 1916): 13. ↩︎

-

Alfred Stieglitz to Anne Brigman, late 1917 or early 1918, Box 8, folders 169–73, Alfred Stieglitz/Georgia O’Keeffe Archive, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University (hereafter cited as AS/OK). ↩︎

-

Alfred Stieglitz to Georgia O’Keeffe, March 31, 1918, AS/OK. ↩︎

-

Anita Pollitzer to Georgia O’Keeffe, December 31, 1915, Box 208, folder 3649, AS/OK. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/32191697?child_oid=32192109 ↩︎

-

O’Keeffe had known Macmahon since 1914, when both were teaching summer courses at the University of Virginia, and by 1916 they had become very fond of one another. ↩︎

-

Georgia O’Keeffe to Arthur W. Macmahon, January 8, 1916, in Roxana Robinson, Georgia O’Keeffe: A Life (Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, 2021), 654. ↩︎

-

The letter’s envelope is postmarked January 1, 1916. ↩︎

-

See Nancy Scott, “The Pollitzer-O’Keeffe Correspondence,” Source: Notes in the History of Art 3, no. 17 (Fall 1985): 34–41; and Clive Giboire, ed., Lovingly Georgia: The Complete Correspondence of Georgia O'Keeffe & Anita Pollitzer, introduction by Benita Eisler (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990), 115. ↩︎

-

See Anne Middleton Wagner, Three Artists, Three Women: Modernism and the Art of Hesse, Krasner, and O’Keeffe (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 35 and n. 12. ↩︎

-

See Louis Kalonyme, "Georgia O'Keeffe: A Woman in Painting," Creative Art 2 (January 1928): xxxiv–xl. In his book, Herbert Seligmann, another Stieglitz friend, recorded Stieglitz uttering the phrase and its origin story in 1926, but used the words At Last rather than Finally: “Stieglitz told today [January 6, 1926] of how he met O’Keeffe . . . a young girl, Anita Pollitzer . . . walked in with a roll of drawings under arm. ‘I’ve been asked by letter not to show anyone these . . . but they belong here’ . . . When Stieglitz saw the first one he said: ‘At Last a Woman on Paper.’” But Seligmann’s book was not published until 1966. See Herbert J. Seligmann, Alfred Stieglitz Talking: Notes of Some of His Conversations, 1925-1931 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Library, 1966), 23. Because capitalization and punctuation of the phrases vary in the literature, they are referred to here to avoid confusion as “Finally, a Woman on Paper,” and “At Last, A Woman on Paper.” ↩︎

-

See Current Biography, June 1941, 62–63. ↩︎

-

See Barbara Buhler Lynes, O’Keeffe, Stieglitz and the Critics, 1916-1929 (Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, 1989; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991); Kathleen Pyne, Modernism and the Feminine Voice: O’Keeffe and the Women of the Stieglitz Circle (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008); and Marcia Brennan, Painting Gender, Constructing Theory: The Alfred Stieglitz Circle and American Formalist Aesthetics (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001). ↩︎

-

See Daniel Catton Rich, Georgia O’Keeffe (Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 1943), 17. ↩︎

-

See Barbara Buhler Lynes, "The Language of Criticism: Its Effect on the Art of Georgia O'Keeffe in the 1920s," in Georgia O'Keeffe: From the Faraway, Nearby, eds. Ellen Bradbury and Christopher Merrill (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Press, 1992), 43–55. Reprinted in Women’s Art Magazine, no. 51 (March/April 1993): 4–9; and “Georgia O’Keeffe, An American Phenomenon: Issues of Identity,” in Georgia O’Keeffe, ed. Barbara Buhler Lynes (Milan: Skira Editore, 2011), 13–20. In the 1920s, O’Keeffe waged a silent campaign to separate her art from sexualized readings of it, and in the statement for her 1939 exhibition she first openly voiced her concern: “Well—I made you take time to look at what I saw and when you took time to really notice my flower you hung all your own associations with flowers on my flower and you write about my flower as if I think and see what you think and see of the flower—and I don't.” Statement in Georgia O'Keeffe: Exhibition of Oils and Pastels (New York: An American Place, 1939), n.p. ↩︎

-

See Rich, Georgia O’Keeffe, 21. ↩︎

-

Stieglitz also exhibited O’Keeffe’s work in New York that year. ↩︎

-

See Janet Hollis, "Two American Women in Art—O'Keeffe and Cassatt," Delphian Quarterly 28 (April 1945): 10; and “Georgia O'Keeffe: ‘Finally, A Woman on Paper,’” U.S.A. An American Review 2, no. 8 (1945): 95–96. ↩︎

-

Museum of Modern Art Press Release. ↩︎

-

See Barbara Buhler Lynes, “Georgia O’Keeffe and Feminism: A Problem of Position,” in The Expanding Discourse: Art History and Feminism, eds. Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard (New York: HarperCollins, 1992), 436–49. ↩︎

-

See Gladys Oaks, “Radical Writer and Woman Artist Clash Uses—This is an Industrial Age, Michael Gold Tells Georgia O'Keefe [sic], Who Thinks He's All Mixed Up,” The World, March 16, 1930, Women's Section 3. See also Lynes, “Georgia O’Keeffe and Feminism: A Problem of Position”; Brennan, Painting Gender, Constructing Theory; and Linda M. Grasso, Equal under the Sky: Georgia O’Keeffe & Twentieth-Century Feminism (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2017). ↩︎

-

See Giboire, Lovingly Georgia, 117. ↩︎

-

See Henry McBride, "O'Keeffe at the Museum: An Exhibition that Confirms the Opinion Long Held by the Public," The Sun (New York), May 18, 1946, 9. ↩︎

-

See James Johnson Sweeney to Mr. [Monroe] Wheeler, May 11, 1946; and Mr. [Monroe] Wheeler to Photography Department, May 13, 1946, Museum of Modern Art Exhibitions, 319.3, Museum of Modern Art Archives. ↩︎

-

More than 40 years after Stieglitz’s death, O’Keeffe helped organize an extensive exhibition of his “Woman on Paper” at the Museum of Modern Art in 1978, the first project she worked on before her death that brought Stieglitz’s work and his reputation back into the spotlight. Another was the 1983 Stieglitz exhibition at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. ↩︎

-

See Anita Pollitzer, Harper's Bazaar 80, no. 2816 (August 1946): 169. ↩︎

-

See Anita Pollitzer, "That’s Georgia," Saturday Review of Literature 33, no. 44 (November 4, 1950): 41–43; and A Woman on Paper (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1988), 48. Pollitzer had to have inserted the phrase before O’Keeffe gave the letters she had received from her to the Beinecke Library, because the pencil phrase is in the 1915 letter housed there. O’Keeffe gave a great deal of correspondence and other materials to the library in 1949, but detailed lists of what they included have not been discovered, thus making it impossible to establish a firm date for O’Keeffe’s gift. ↩︎

-

See Art News 45, no. 4 (June 1946): 51. ↩︎

-

Ironically, none of the charcoal abstractions O’Keeffe completed in 1915 were in the exhibition, and it included only three works on paper. See Barbara Buhler Lynes, Georgia O’Keeffe: Catalogue Raisonné (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999), entries 64, 99, and 157. ↩︎