Barbara Buhler Lynes’s O’Keeffe, Stieglitz and the Critics, 1916-1929 was published in 1989, three years after Georgia O’Keeffe’s death, and three years before Lynes was asked to write Georgia O’Keeffe: Catalogue Raisonné, published in 1999. The 1989 publication was as thorough a review of O’Keeffe’s early critical literature as anyone could have undertaken at this time; it was exhaustively footnoted, with a selected bibliography running to 18 pages. Absent from this study, however, was much of O’Keeffe’s personal correspondence, including hundreds of letters exchanged in these years between Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz. This material, held at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University, was restricted (per O’Keeffe’s instructions) for 25 years after her death. Contained within this correspondence are glimpses of O’Keeffe’s and Stieglitz’s personal responses to this very public criticism—insights that were not available to Lynes in 1989. Nevertheless, O’Keeffe, Stieglitz and the Critics remains a work of reference. It details the early reception of O’Keeffe’s art in New York and the exhibitions that made her the most-talked-about artist in the country. The present publication stands in this tradition.

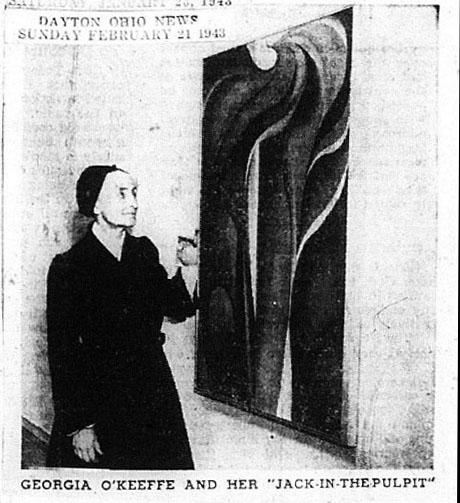

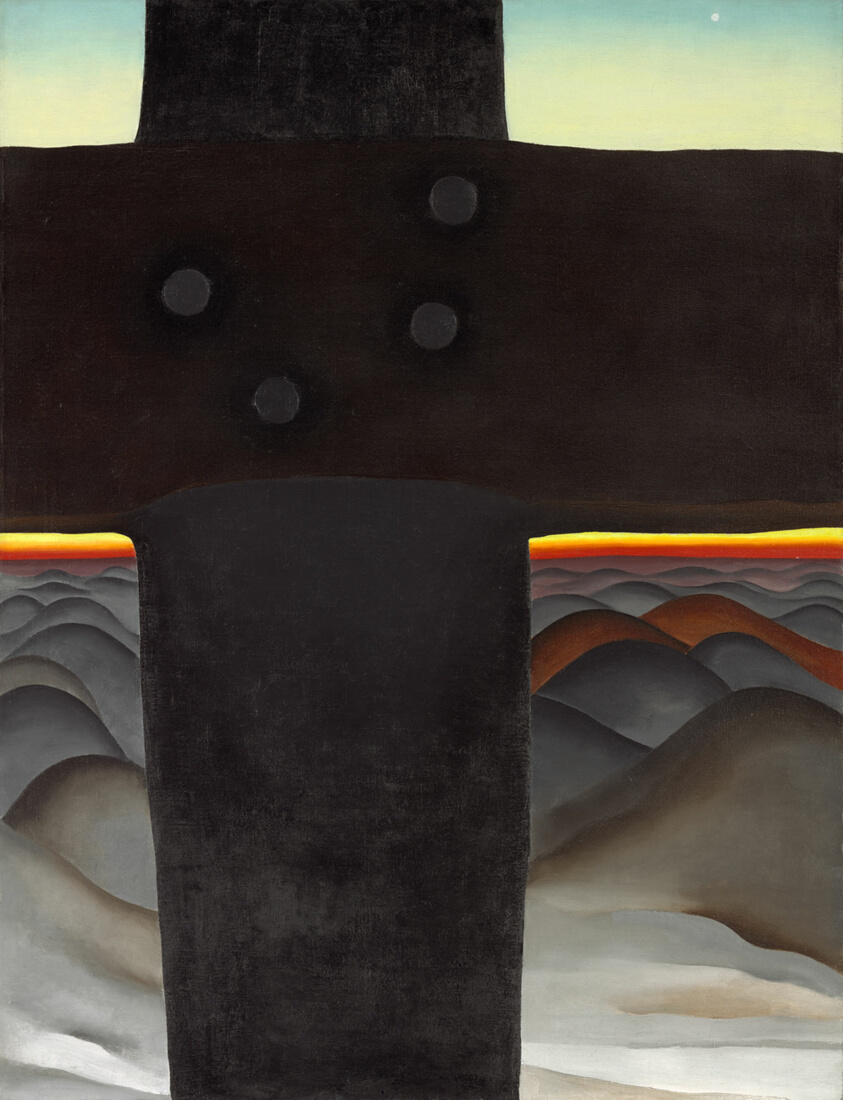

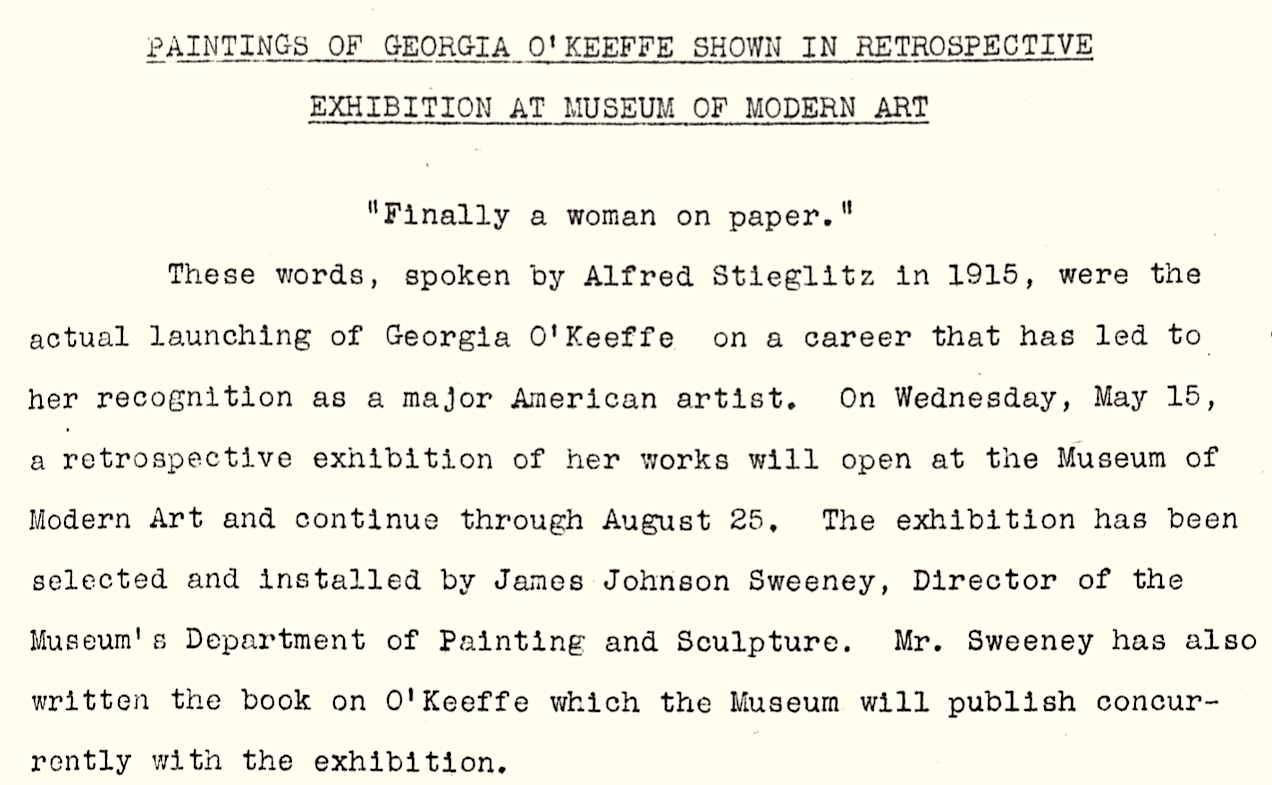

There would have been no critics without exhibitions, and the history of O’Keeffe’s exhibitions (and their accompanying literature) continues to this day. We understood, from the outset, that no publication of this kind could hope to have the “final word.” It fell to us, therefore, to make a selection: a handful of case studies that together could form a narrative. In making this selection we sought help, and I would like to gratefully acknowledge input received from the curatorial and research team including Jennifer Foley, Liz Ehrnst, and Liz Neely as well as from the authors of the essays, whom we also consulted on this question. We concluded that we would concentrate on exhibitions organized during the artist’s lifetime, selecting pivotal examples from 1917 to 1975. The result is the four essays that follow. The first and last of these, by Alexandra Dean and Amy Von Lintel, in fact address more than a single exhibition. Dean revisits the critical responses to O’Keeffe’s earliest exhibitions in New York, the origin of the “cult of personality” surrounding the artist, and more broadly the boundaries between her art and life; Von Lintel tells the story of O’Keeffe’s connection to the West by way of Texas, including exhibitions in both Dallas and Fort Worth. The second and third essays in this group, by Sarah Kelly Oehler and Barbara Lynes, focus on O’Keeffe’s first retrospective exhibitions in Chicago and New York; at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1943, and the Museum of Modern Art in 1946.

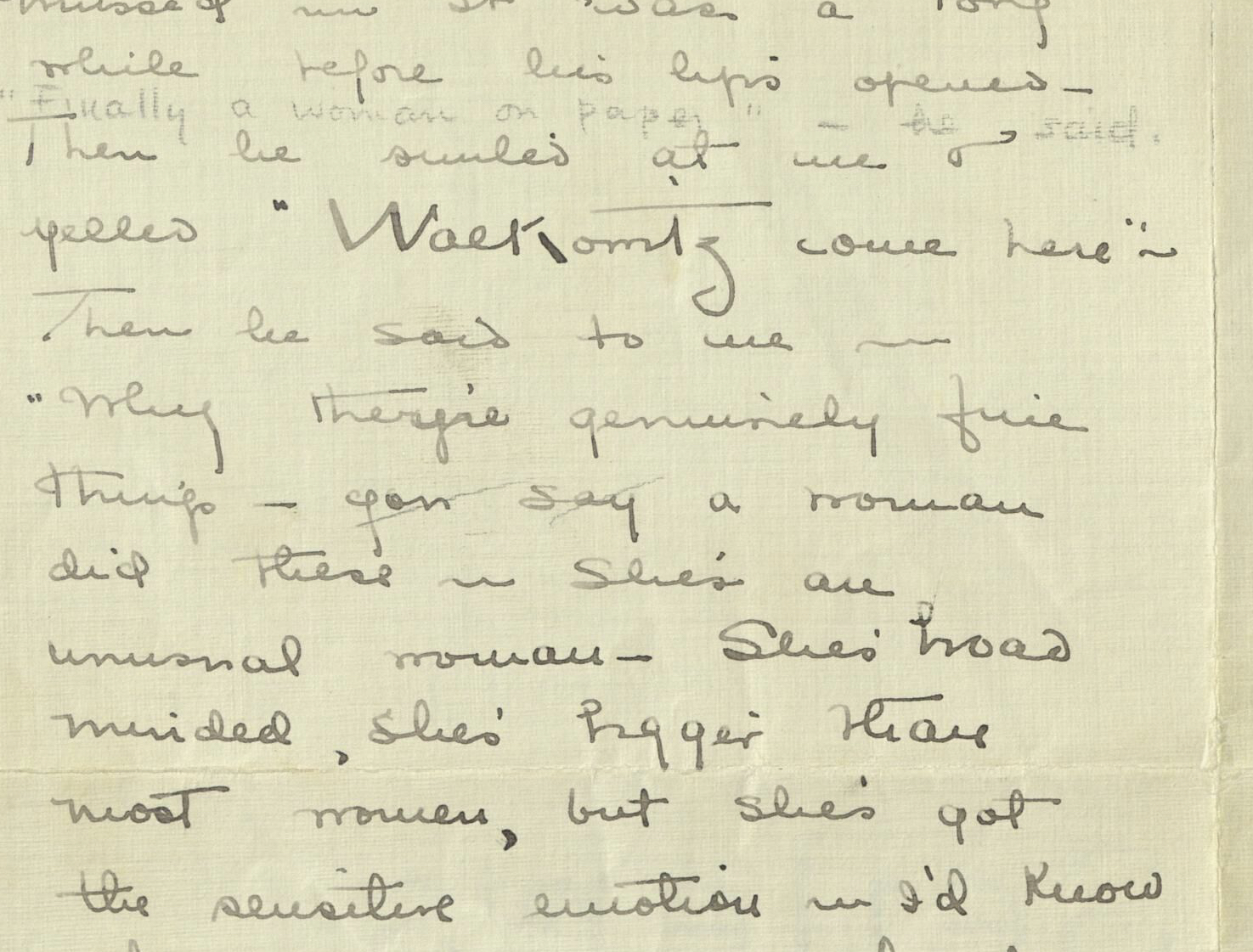

In place of a single “institutional” account, we are gratified that these four contributors offer a plurality of voices. Nevertheless, certain themes run throughout this publication that weave these individual narratives together. Alongside contemporary responses to O’Keeffe’s art, we witness an early emphasis on the identity of the artist herself in discussions of these exhibitions. This is nowhere more emphatically seen than in the phrase, attributed to Alfred Stieglitz, “Finally a woman on paper.” Lynes’ debunking of this quote’s being uttered by him in 1915 as mere legend serves to recall that the O’Keeffe narrative is still very subject to revision, even as it illustrates the durability of the prejudices and apocrypha that continue to shape our understanding of Georgia O’Keeffe.