In January 1943, Georgia O’Keeffe returned to Chicago. She had lived in the city in her early adulthood: first in 1905–6 when she studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and again, two years later, when she worked unhappily as a commercial illustrator before contracting measles, forcing her to quit the city. Her return to Chicago more than 30 years later, however, was far more triumphant.

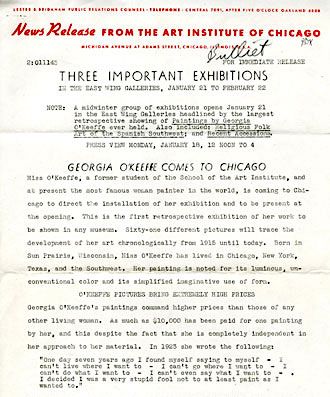

The occasion was a momentous one. The Art Institute of Chicago was mounting Georgia O’Keeffe, Paintings, 1915-1941, a large-scale display of her artwork that marked several “firsts” for O’Keeffe in what was already a significant career: her first museum retrospective, far more comprehensive in breadth than her 1927 exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum of Art; her first solo exhibition to be held outside of New York City; and the largest gathering of her works since 1923 (figure 1).1 That it was held in the Midwestern metropolis she had once called home, not far from her birthplace in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, further enhanced its cachet. Although little noted in the scholarship on O’Keeffe—generally overshadowed by her 1946 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art—the Chicago exhibition established the canon of her work up until 1943, produced a catalogue that would become the defining statement of O’Keeffe’s early career, and reinvigorated her connections to Chicago. The exhibition would also influence O’Keeffe’s decisions regarding the estate of Alfred Stieglitz, the renowned photographer and art dealer, and also her husband, who died three years later, in 1946. Required to determine which institutions would receive his sizable collection of European and American art, O’Keeffe seized the opportunity to designate her own paintings—many of which were in the Art Institute show—as part of these donations.

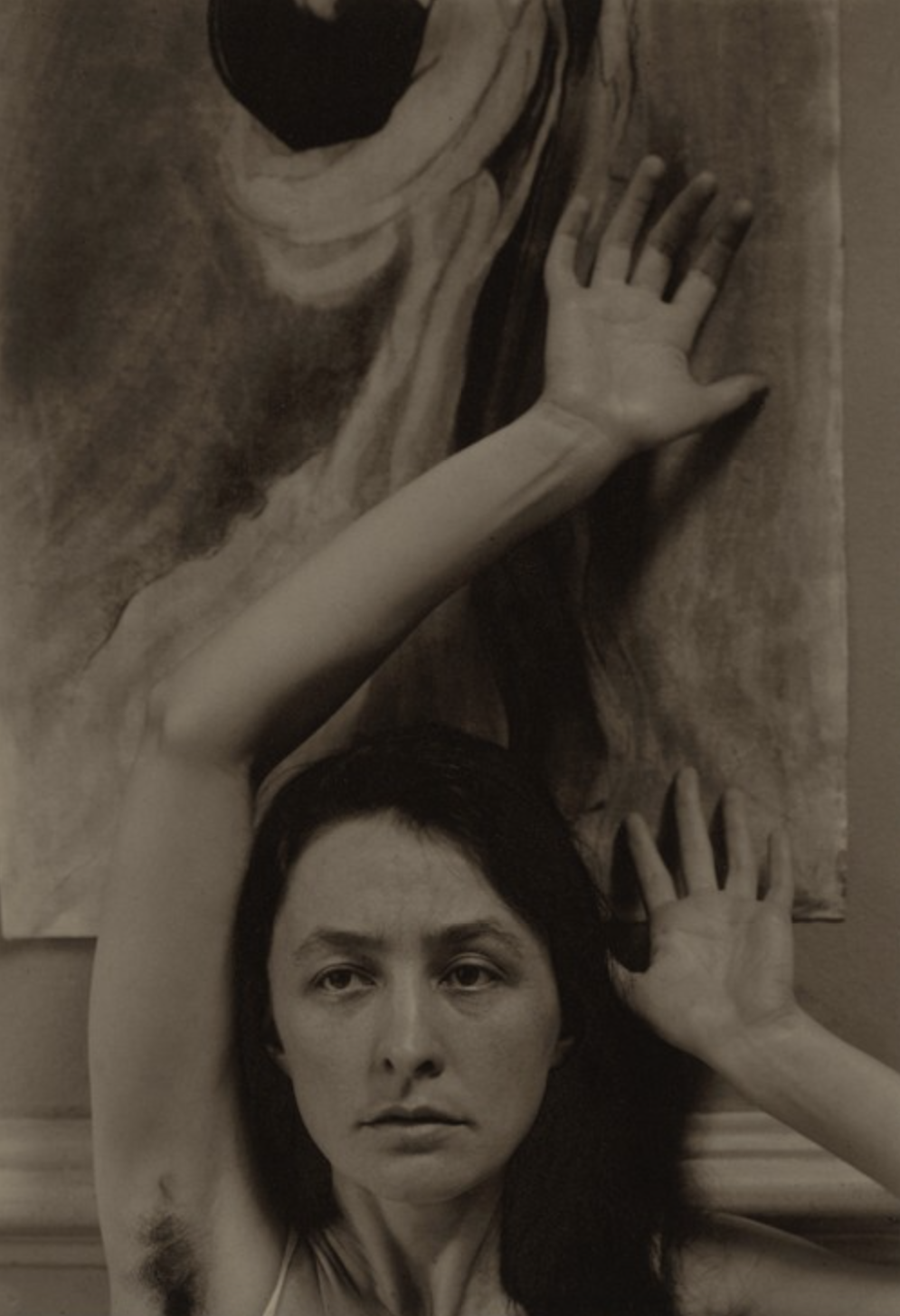

The Chicago exhibition originated thanks to the discerning eye of Daniel Catton Rich, director of the Art Institute (figure 2).2 Rich and O’Keeffe met in 1929, when both were guests of Mabel Dodge Luhan, the famed patron of the arts, at her home in Taos, New Mexico. At the time, Rich was the assistant curator of painting and sculptures at the Art Institute and was already familiar with O’Keeffe’s art thanks to Stieglitz’s exhibitions in the 1920s. He continued to follow her career from afar, and, in the spring of 1941, broached the possibility of an exhibition.3

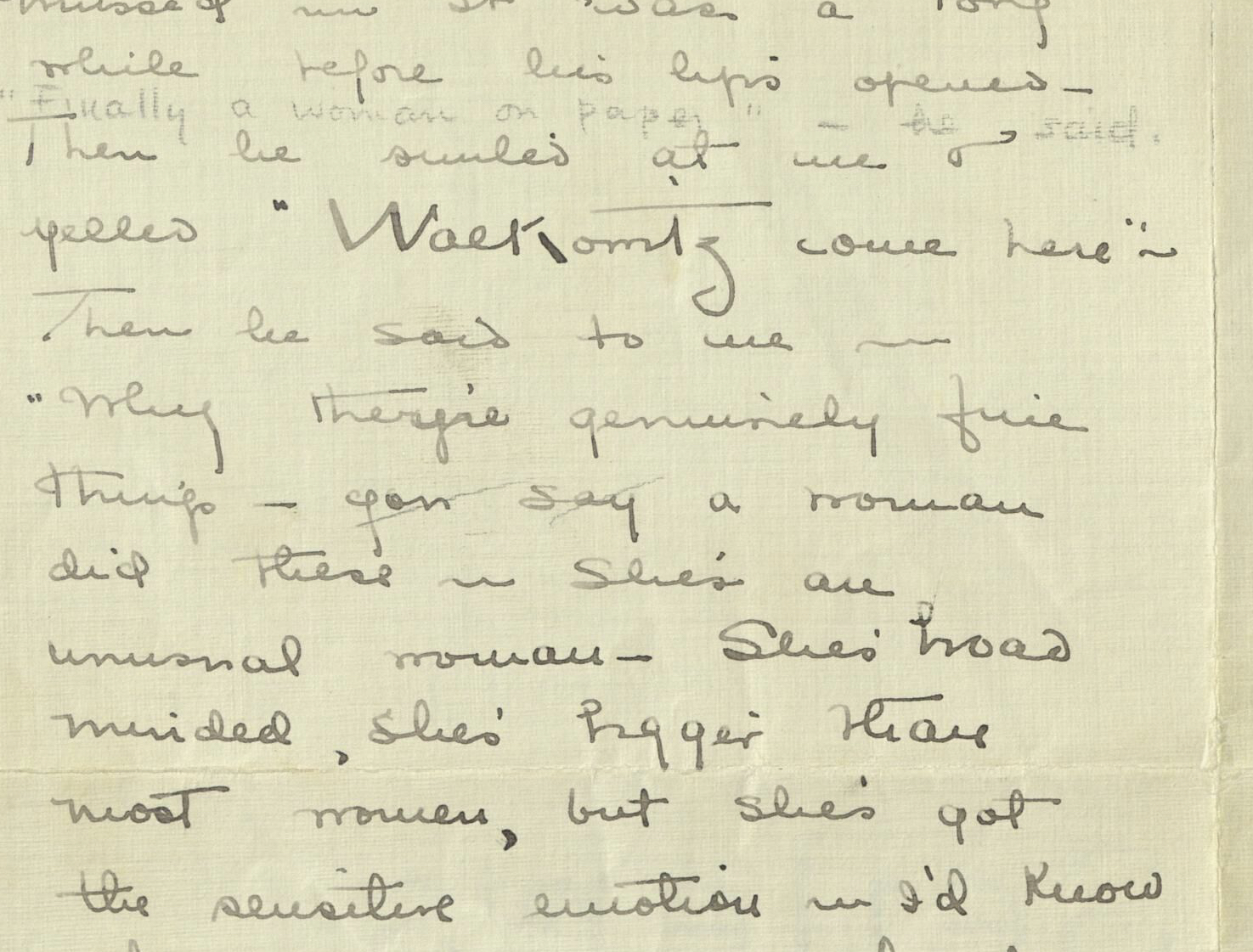

From the beginning, Rich conceived of the show as a career-spanning exhibition that would demonstrate the beauty and range of her art to eager Chicago audiences. As he explained to O’Keeffe in a letter: “I have long admired your work and feel that a selection of it showing your changes and developments would be greatly appreciated by our public, already keenly aware of your place in American art.”4 O’Keeffe must have encouraged Stieglitz (in his role as her art dealer) to agree, as he wrote to her while she stayed at Ghost Ranch that summer: “I’m returning Mr. Rich’s letter. Thanks. Yes a show of yours properly selected will be an eye opener.”5 During trips to New York that fall and winter, O’Keeffe, Rich, and Stieglitz discussed the exhibition further, and agreed to two stipulations: that Rich would allow O’Keeffe to install the exhibition herself, and that the Art Institute would acquire a major work from the show.6

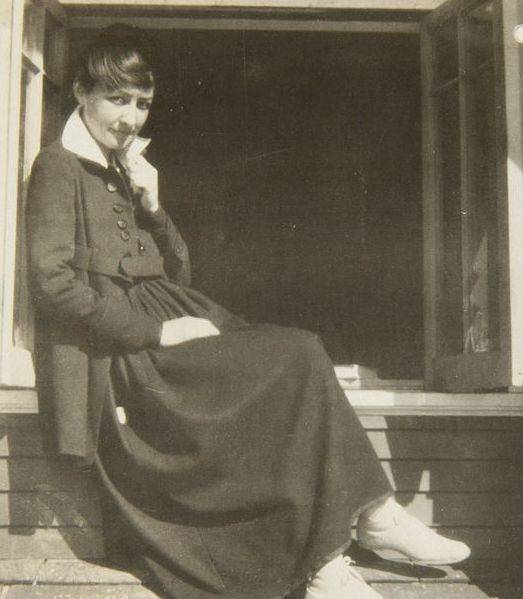

O’Keeffe arrived in Chicago on Monday, January 11, 1943, and checked into the Blackstone Hotel, located on Michigan Avenue several blocks south of the Art Institute. The next few days were a whirlwind of press interviews and gallery installations as O’Keeffe and Rich prepared for the exhibition’s scheduled opening on Thursday, January 21. O’Keeffe threw herself into hanging the exhibition, an activity that fascinated reporters unused to a woman so rigorously attending to such matters:

With Miss O’Keeffe . . . the hanging of a picture is as important as its painting. She is a slight, wiry little woman with a face of exquisite, coinlike beauty, done almost in pale sepia, and brown hair wound in a coronet, but she lugged her heavy paintings, in their frames of copper and stainless steel, like an automaton. Before she was thru, of course, she had Daniel Catton Rich, Institute director, discarding his jacket and racing around in a yellow sweater and maroon tie to help; and before she was really thru, she was in bed with the flu.7

Indeed, O’Keeffe retreated to the Blackstone Hotel to recuperate after three days of installation, but not before insisting that the Art Institute repaint the largest of the three galleries—reportedly a violet color—which resulted in two white rooms and one in a greenish-gray hue.8

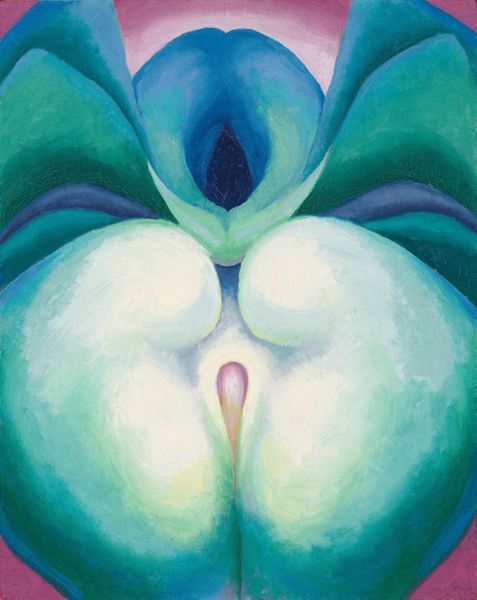

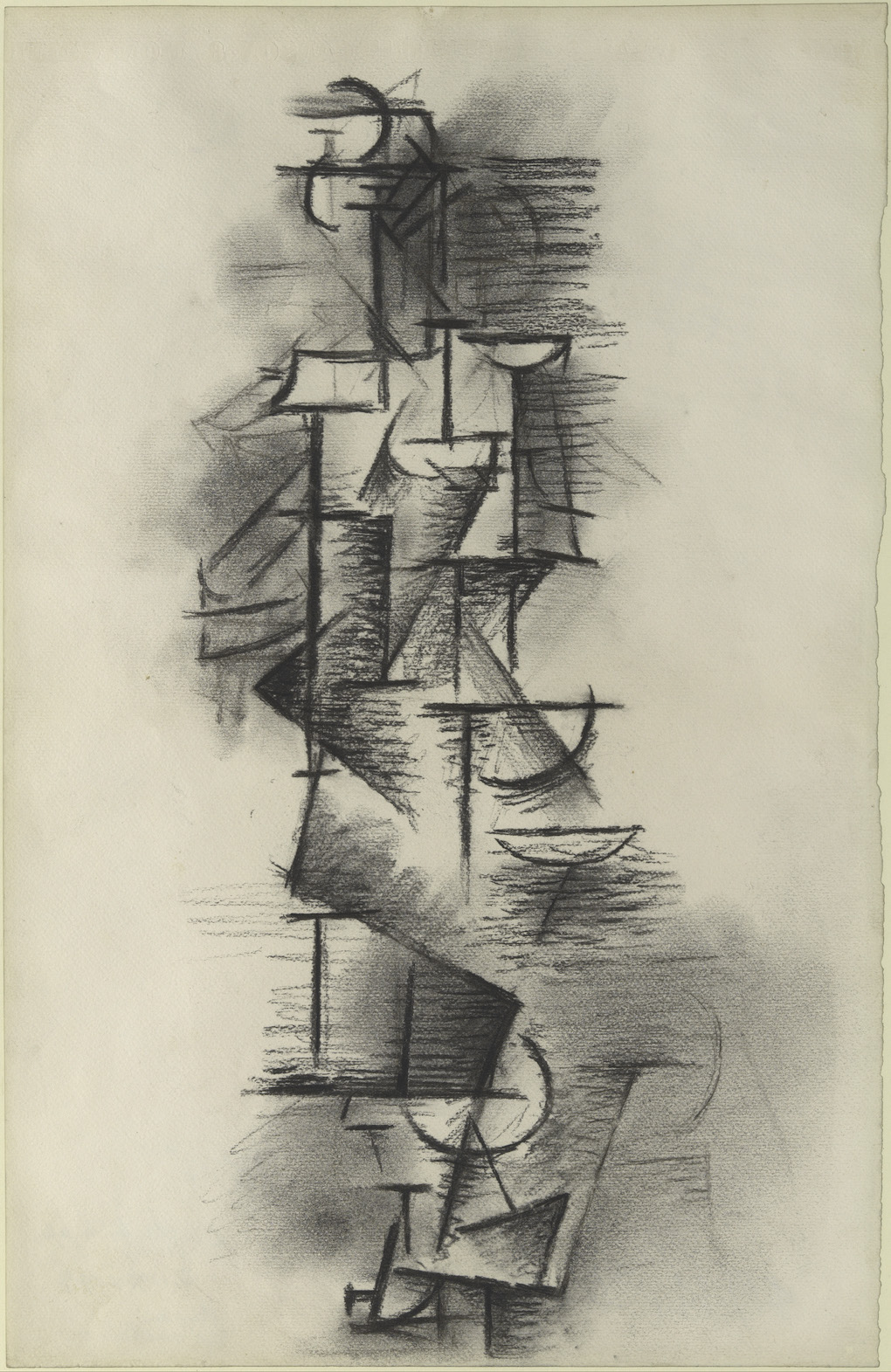

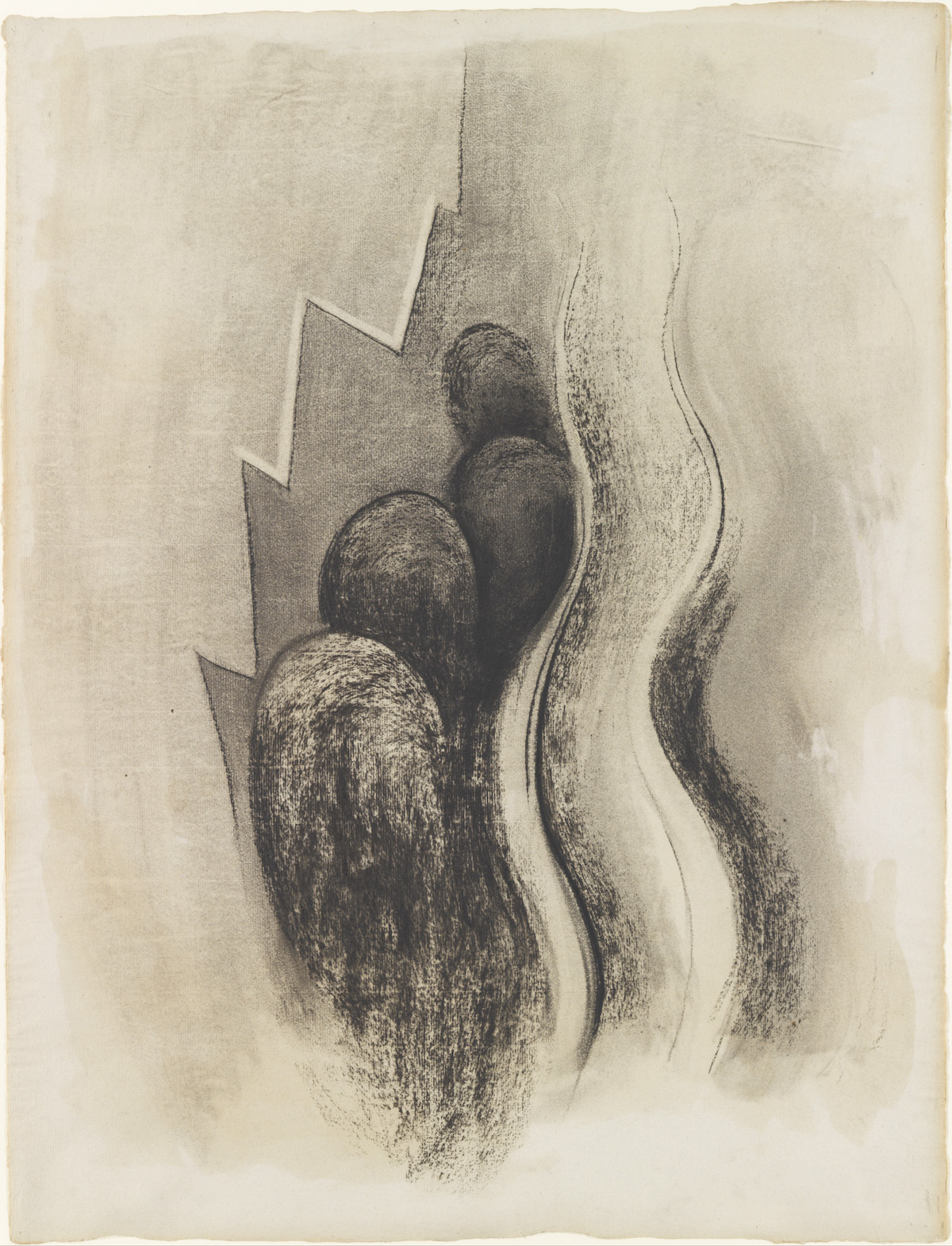

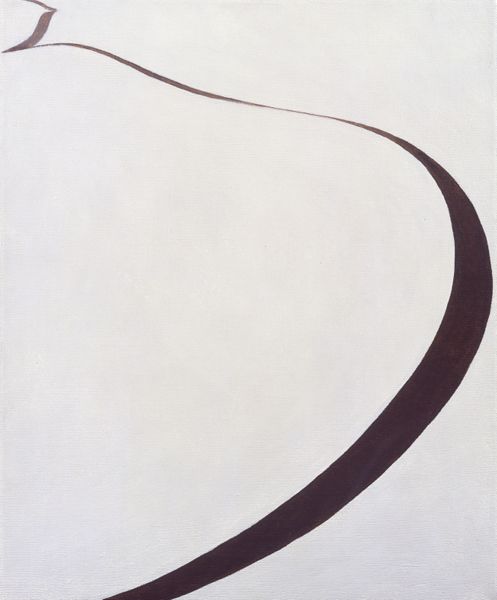

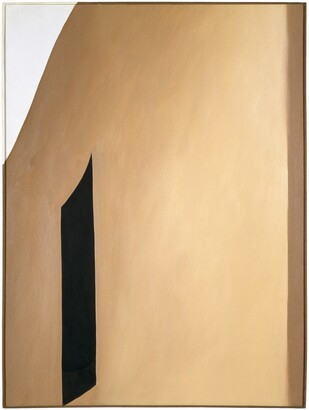

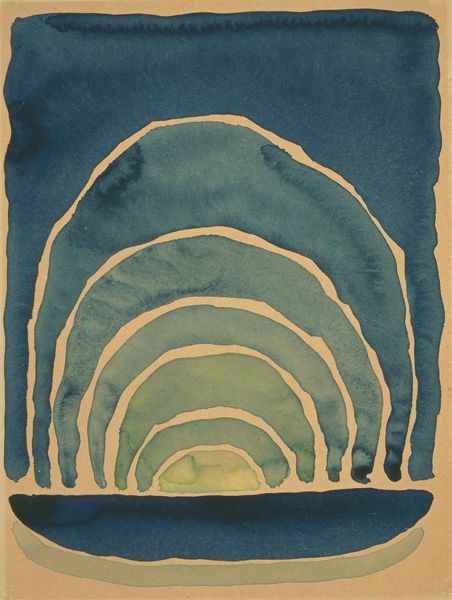

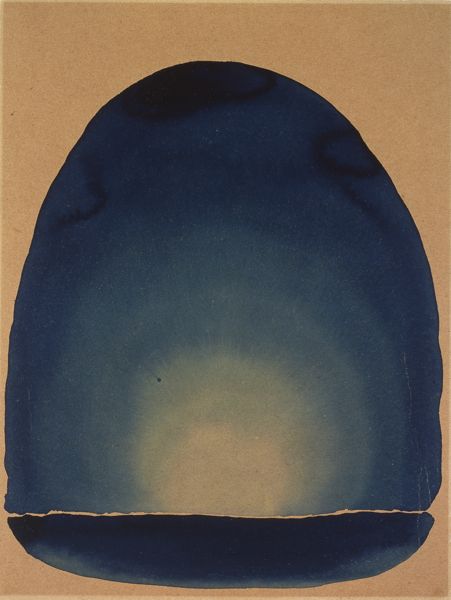

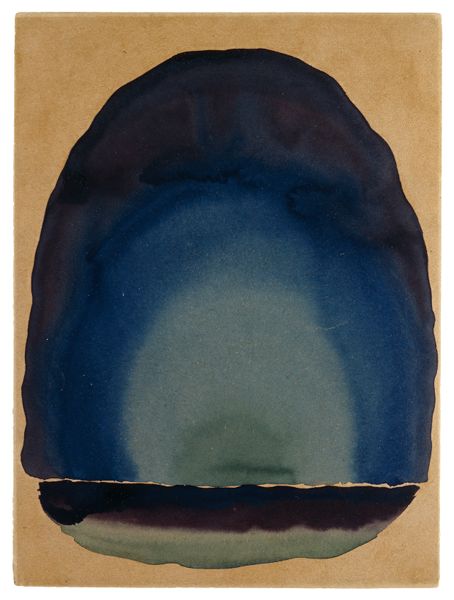

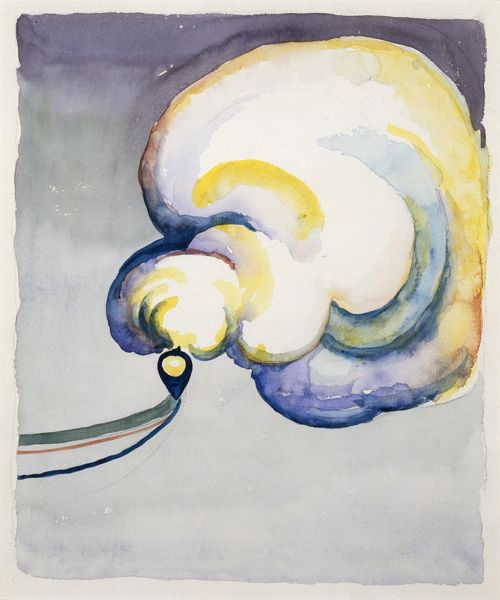

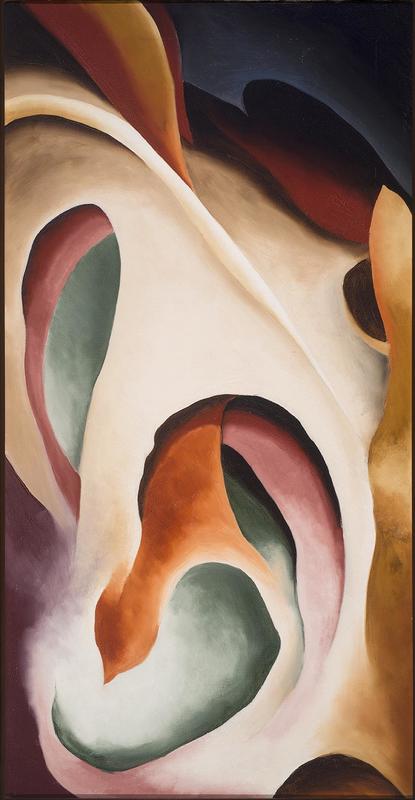

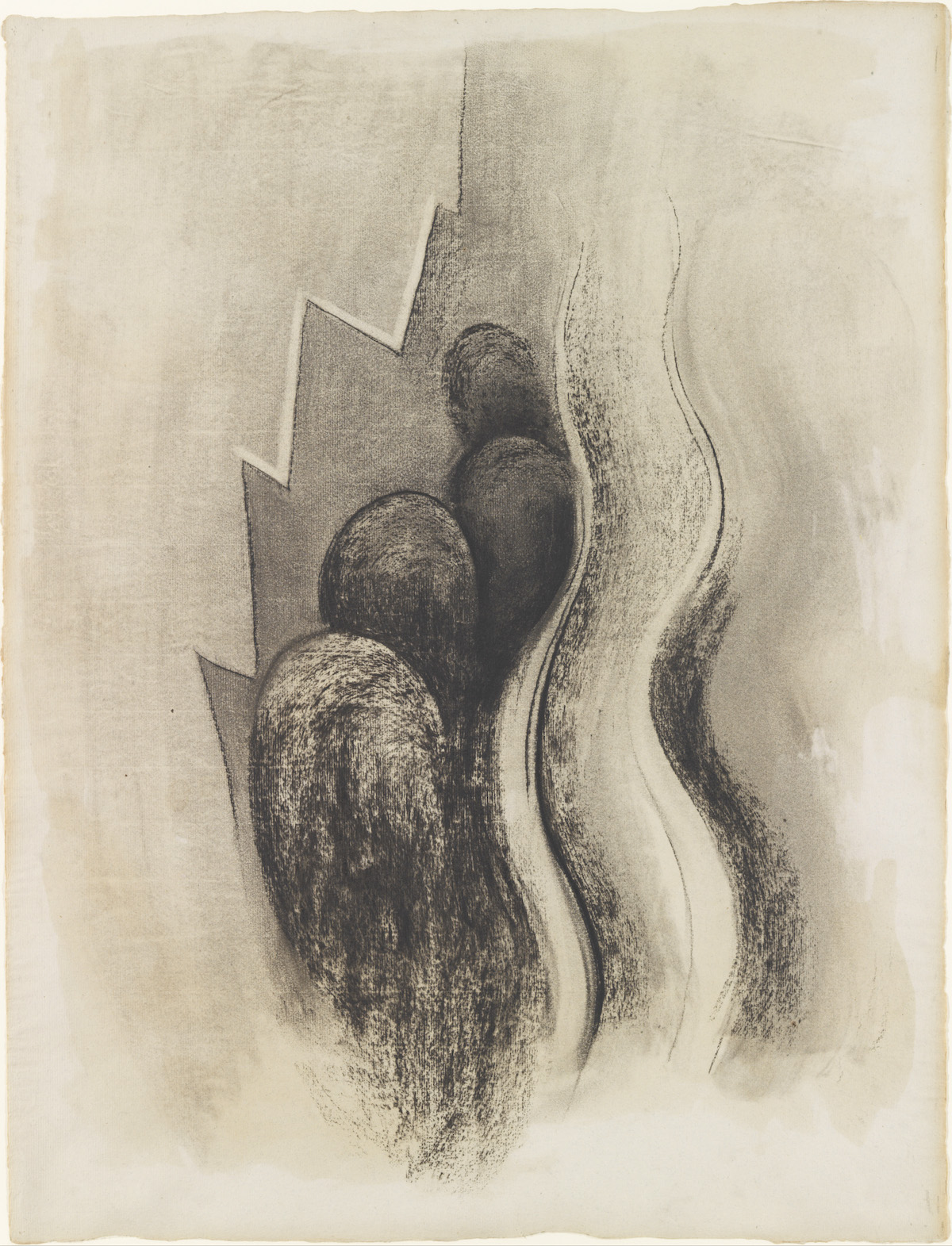

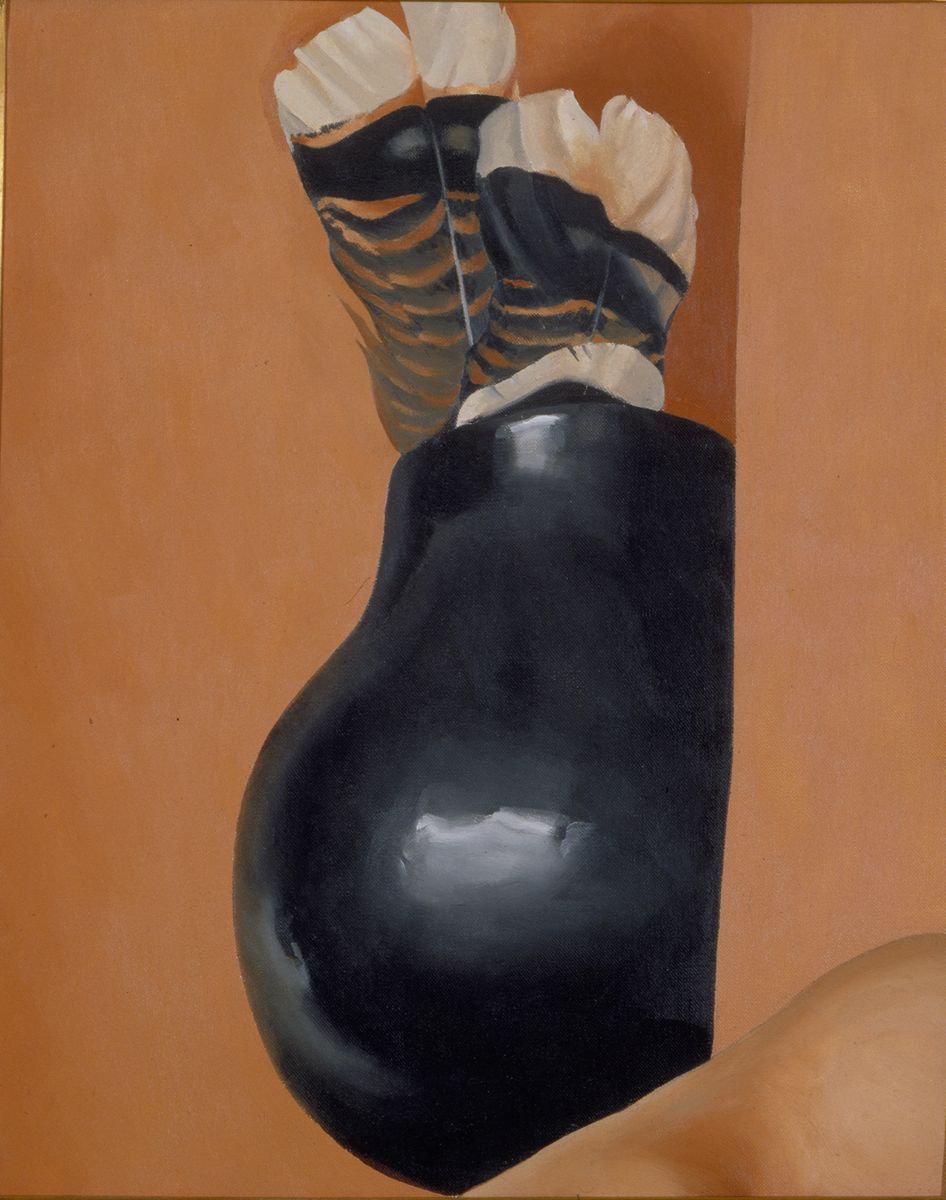

The exhibition included 61 works, all lent through Stieglitz’s An American Place gallery.9 As the chronologically arranged catalogue demonstrates, they ranged from early career works to her most recent canvases, starting with two drawings of around 1915–17: the watercolor Blue Lines X / Blue Lines and an untitled charcoal drawing (Drawing XIII / No. 13. Special) (figures 4–5). These were also the only two works on paper selected for inclusion.10 The latest paintings shown were Red Hills and Bones and Turkey Feathers and Indian Pot, two oils of 1941 (figures 6–7).11 In its scope, the display differed from all her past exhibitions, whether at Stieglitz’s galleries or the Brooklyn Museum, in that it featured more than 25 years of work. The retrospective revealed an expanded view of O’Keeffe’s work in other ways too: It demonstrated her varied subject matter, from abstract motifs to flowers and other natural forms to the stunning Southwestern landscape. It showcased the many locations she had visited or called home that inspired her creativity, including Lake George, Manhattan, New Mexico, and Canada. And it revealed her deployment of a dramatic range of canvas sizes as well as her penchant for working through certain motifs in multiple compositions.

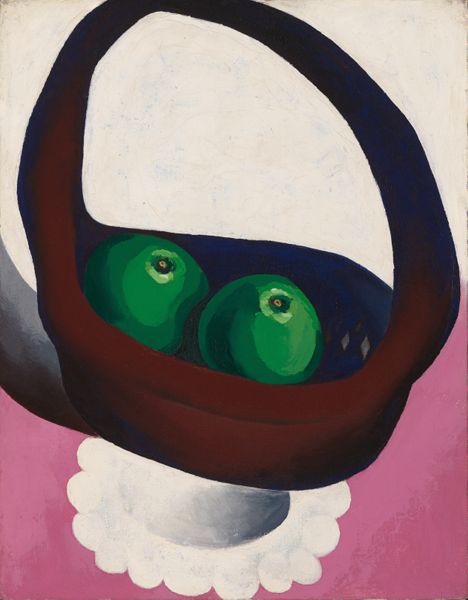

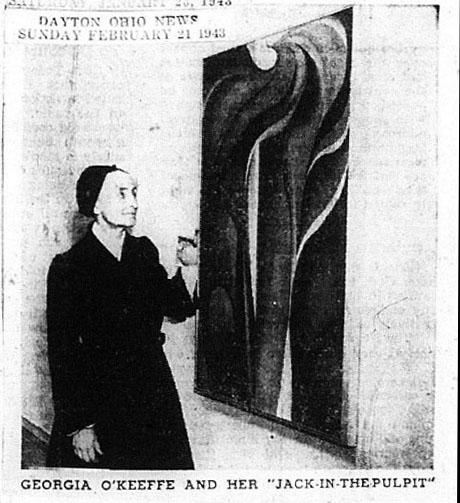

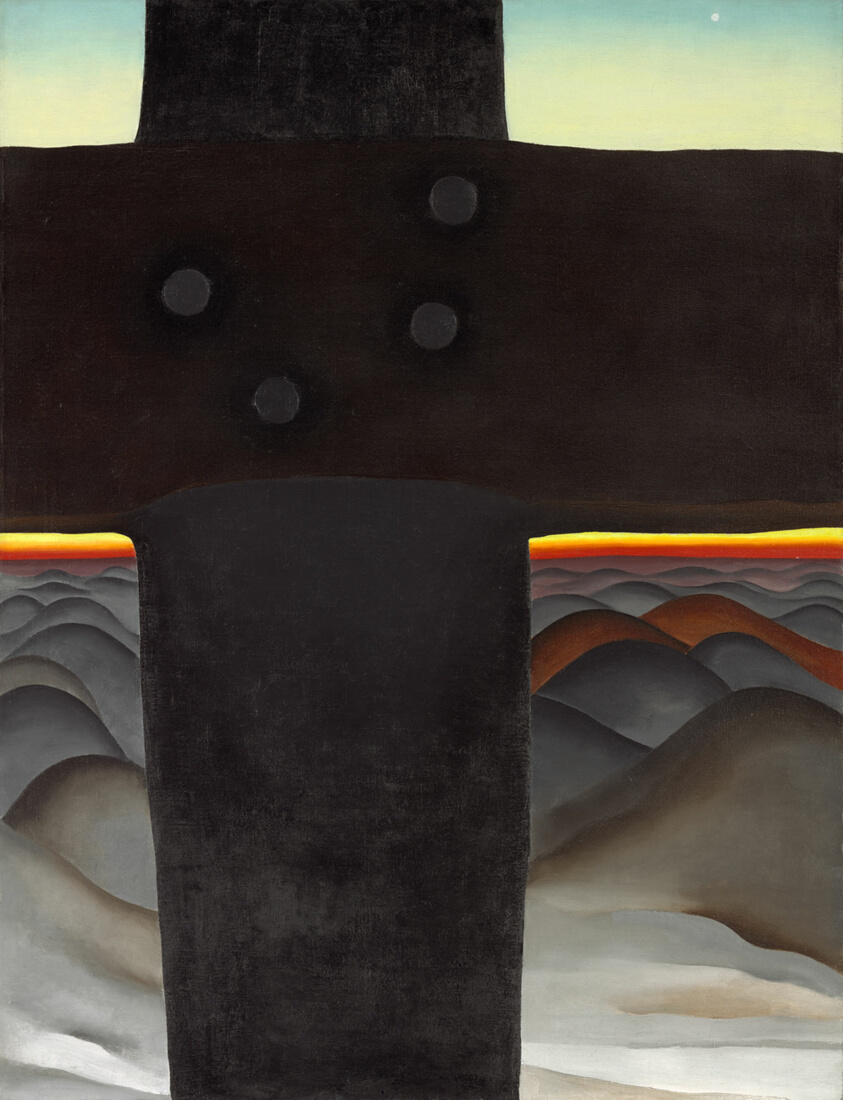

This diversity was highlighted in the way O’Keeffe chose to display her art; as three archival photographs of the galleries (figures 8–10) demonstrate, O’Keeffe hung the works based on her own logic and aesthetic preferences. Rather than segregating her painting into discrete categories, she deliberately juxtaposed works of different subjects, decades, and locations. For example, in the small white room, she placed Black Iris (1926), an enlarged flower painting, on a wall adjacent to Dark Mesa with Pink Sky (1930) and Black Cross, New Mexico / Black Cross (1929), allowing their formal structures and color schemes to resonate.12 She also embraced the scale differences between her paintings: on the other side of the gallery she positioned East River from the 30th Story of Shelton Hotel (1928)—one of the largest formats used by O’Keeffe at the time, at 30 inches high by 48 inches wide—next to the relatively diminutive Red Poppy (1928), measuring seven by nine inches.13 Two large abstract works, Abstraction (1926) and From the Lake No. 3 (1924), can be seen adjacent to Red Poppy, further underscoring the variations among theme and size in her oeuvre.14 O’Keeffe did, however, opt to display all six of the Jack-in-the-Pulpit canvases (1930) on one wall of the large white gallery, encouraging visitors to discern for themselves how she used a single motif to experiment with color, form, and scale.15

The exhibition was an opportunity for O’Keeffe, in collaboration with Rich, to establish the visual parameters of her career up until that point, and it revealed her preferences in exhibition display. But equally important was the essay Rich wrote for the catalogue, which would become the defining statement of O’Keeffe’s early career. Rich opened with an assertion that continues to resonate today: “The art of Georgia O’Keeffe is a record of intense emotional states resolved into crystalline form. Her ability to charge abstract elements of line, color, and mass with passionate meanings is as notable as her fastidious and immaculate craftsmanship.”16 The essay explored her life and career, touching on familiar milestones. These included her early schooling, her studies with Arthur Wesley Dow, and her teaching in Texas. It described her groundbreaking work with charcoals, and recounted the story of her friend Anita Pollitzer sharing them with Stieglitz. Finally, it detailed her partnership with Stieglitz and her 1929 trip to the Southwest. Indeed, as biographer Roxana Robinson has noted, Rich’s essay “contained the biographical structure of the O’Keeffe myth as it would be retold again and again.” Rich did not, however, only convey biographical facts; he also interwove a sensitive analysis of many of the paintings in the exhibition that undoubtedly developed from his conversations with the artist. Acknowledging that in her fifth decade O’Keeffe was “still at work with intense energy and what the next years will bring forth no one (not even herself) can foresee,” Rich ultimately concluded that “the place of Georgia O’Keeffe is secure” and that “American painting of our day is infinitely richer for her triumphant vision.”17

Extensive newspaper coverage of the exhibition helped reinforce O’Keeffe’s reputation as one of the preeminent artists of the era. No doubt, the press’ fascination with the show related significantly to her status as a famed woman artist (figure 11). Reporters eagerly detailed the social events planned for O’Keeffe (which were truncated due to her illness) and commented on her outfits and appearance. But reviews of her paintings were positive, especially notable given that seemingly only four paintings by O’Keeffe had previously been seen in the city.18 “The three galleries glow with the clear, clean, luminous color of her [work],” said one critic, further noting the “combination of intense emotion, penetrative imagination, and great delicacy of feeling in her art.”19 Another author concluded, “If you like her work, you love it; if you don’t, you can’t forget it.”20 And significantly, the Associated Press released a lengthy piece on O’Keeffe and the exhibition by correspondent W. W. Hercher, who interviewed her on her first day in Chicago.21 His article, in which he described the show as “the artistic event of the first magnitude,” was syndicated widely and undoubtedly heightened her visibility throughout the nation.22

The O’Keeffe retrospective thus had several important outcomes: it codified a desirable narrative of her art and work through Rich’s essay; it established a core group of important works; and it helped broaden her reputation. It also impacted the Art Institute’s collection as, true to their agreement, Rich purchased Black Cross, New Mexico from the show (figure 12). Heralded by the Chicago press, it was the first O’Keeffe painting to enter the permanent collection of the museum, and is a key example of the work she produced during her first summer in the Southwest.

The 1943 exhibition also directly influenced O’Keeffe’s subsequent decisions in placing the Alfred Stieglitz Collection in a variety of institutions. When her husband died in 1946, O’Keeffe had the overwhelming task of distributing his vast collection of American and European modernist paintings, drawings, and photographs, with major gifts going to the Art Institute of Chicago, Fisk University, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1949. O’Keeffe’s friendship with Daniel Catton Rich, as established through the 1943 show, played a significant role in this; he became one of her closest advisors regarding the Stieglitz Collection.23 Numerous letters between the two demonstrate the complexity of their work. In the process of organizing the dispersal of the Stieglitz Collection with Rich, O’Keeffe also made numerous gifts of her own paintings (often placing them on long-term loan to the institutions first), designating them as future acquisitions to the Stieglitz Collection. Of the 61 works chosen for the 1943 exhibition, 24 of them—or well over one-third—would later be donated to museums, including an additional six paintings given to the Art Institute between 1947 and 1987.

The 1943 retrospective at the Art Institute of Chicago was thus a major milestone for the artist. It presented key works from across her career, offering visitors a chance to understand and assess the development of her art. Rich’s essay enhanced this understanding with its sensitive analysis. The exhibition also introduced her work to audiences outside of New York City and brought her widespread visibility through local and syndicated press coverage. O’Keeffe and Rich’s fruitful collaboration would, however, have an even greater impact through her subsequent donation of works from the Stieglitz Collection. The added allocation of her own paintings amplified her consistent prominence on the walls of museums across the country, reinforcing the growth of her reputation as one of the central figures of American Modernism. The 1943 retrospective thus played a pivotal role as the artist began considering which paintings would become part of her enduring legacy.

Notes

Note on titles of works: Institutional titles and dates for O’Keeffe’s works sometimes vary from first titles and dates established by Georgia O’Keeffe: Catalogue Raisonné (1999), whose entries explain changes. Here institutional titles and dates are listed first followed by those in the Catalogue Raisonné.

-

In 1923, Alfred Stieglitz organized Alfred Stieglitz Presents One Hundred Pictures: Oils, Water-colors, Pastels, Drawings, by Georgia O’Keeffe, American at Anderson Galleries in New York. ↩︎

-

For information regarding Rich, see John W. Smith, “The Nervous Profession: Daniel Catton Rich and the Art Institute of Chicago, 1927-1958,” Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 19, no. 1 (1993): 58–79, 105–7. ↩︎

-

Rich recalled the circumstances of their 1929 meeting in Daniel Catton Rich, “I Met Her in Taos,” Worcester Sunday Telegram, October 30, 1960, 6–8. In this recollection he speculated that they met again in New York in 1942, but a letter from Rich to O’Keeffe in May 1941 demonstrates that they must have reconnected during the winter of 1940–41. Daniel Catton Rich to Georgia O’Keeffe, May 26, 1941, Alfred Stieglitz/Georgia O’Keeffe Archive, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library (hereafter cited as YCAL), MSS 85, Box 179, folder 2973. Lisle cited the erroneous 1942 date in her biography; see Laurie Lisle, Portrait of an Artist: A Biography of Georgia O’Keeffe (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press), 251. ↩︎

-

Daniel Catton Rich to Georgia O’Keeffe, May 26, 1941, YCAL, MSS 85, Box 179, folder 2973. ↩︎

-

Alfred Stieglitz to Georgia O’Keeffe, June 2, 1941, YCAL, MSS 85, Box 76, folder 1602. ↩︎

-

Lisle, Portrait of an Artist, 252. ↩︎

-

Marcia Winn, “Front Views and Profiles: It’s a Personal Matter,” Chicago Tribune, January 22, 1943, 15. ↩︎

-

Lisle, Portrait of an Artist, 252. Lisle indicates that the repainted gallery was originally violet; her source is not cited. O’Keeffe herself described the final colors in a letter to Stieglitz; see Georgia O’Keeffe to Alfred Stieglitz, January 19, 1943, YCAL, MSS 85, Box 93, folder 1838. ↩︎

-

Daniel Catton Rich, Georgia O’Keeffe, Paintings 1915-1941, exh. cat. (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1943); see https://www.artic.edu/exhibitions/7588/retrospective-exhibition-of-paintings-by-georgia-o-keeffe. It must be noted that as a result of being supplied by An American Place in its entirety, the show, although representative, did not include any paintings previously sold by O’Keeffe. ↩︎

-

Barbara Buhler Lynes, Georgia O’Keeffe: Catalogue Raisonné, 2 vols. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999), 1:64, 1:157. Although dated 1915 in the Art Institute’s catalogue, Blue Lines X is now dated to 1916. ↩︎

-

Lynes, Georgia O’Keeffe, 2:1025, 2:1014. ↩︎

-

Lynes, Georgia O’Keeffe, 1:557, 1:739, 1:667. ↩︎

-

Lynes, Georgia O’Keeffe, 1:620, 1:594. ↩︎

-

Lynes, Georgia O’Keeffe, 1:522, 1:471. ↩︎

-

Lynes, Georgia O’Keeffe, 1:715–20. ↩︎

-

Rich, Georgia O’Keeffe, 9. ↩︎

-

Rich, Georgia O’Keeffe, 36, 40. ↩︎

-

This was reported in Judith Cass, “Miss O’Keeffe’s Paintings to be on Exhibit Here,” Chicago Tribune, January 14, 1943, 11. ↩︎

-

Edith Weigle, “Miss O’Keeffe’s Paintings Filled with Integrity,” Chicago Tribune, January 20, 1943, 9. ↩︎

-

Marcia Winn, “Georgia O’Keeffe—Outstanding Artist,” Chicago Tribune, February 28, 1943, C4. ↩︎

-

Georgia O’Keeffe to Alfred Stieglitz, January 14, 1943, YCAL, MSS 85, Box 93, folder 1838. ↩︎

-

The Art Institute collected many of the syndicated stories from around the country, including as far away as Orlando, Florida; see Art Institute of Chicago Scrapbook, vol. 78, 1943, microfilm 1969 25, reel 13. For just one instance of the phrase “artistic event of the first magnitude,” see W. W. Hercher, “‘Greatest’ Woman Artist Opens Chicago Exhibition,” Telegraph Herald (Dubuque, Iowa), January 24, 1943, clipping, Art Institute of Chicago Scrapbook. ↩︎

-

In 1943, likely to thank Rich personally, O’Keeffe gave him Red Poppy, one of the works in the exhibition; see Lynes, Georgia O’Keeffe, 1:594. ↩︎